Green Lake: Reflections from the Surface of China

1/ Around the Lake

![]() ut the banged-up, green-painted, sheet-metal gate that guards the back entrance to our apartment complex. We say nihao to the young man standing under his crewcut and clad in bright green camo who opens and closes the gate every weekday and stands there 6:30-8:30, 11:30-14:30, 17:30-18:30. He keeps street vendors out. He is wearing a pair of canvas tennis shoes I decided were too small for me. He lives in a one-room structure next to the gate barely big enough for the bunk bed.

ut the banged-up, green-painted, sheet-metal gate that guards the back entrance to our apartment complex. We say nihao to the young man standing under his crewcut and clad in bright green camo who opens and closes the gate every weekday and stands there 6:30-8:30, 11:30-14:30, 17:30-18:30. He keeps street vendors out. He is wearing a pair of canvas tennis shoes I decided were too small for me. He lives in a one-room structure next to the gate barely big enough for the bunk bed.

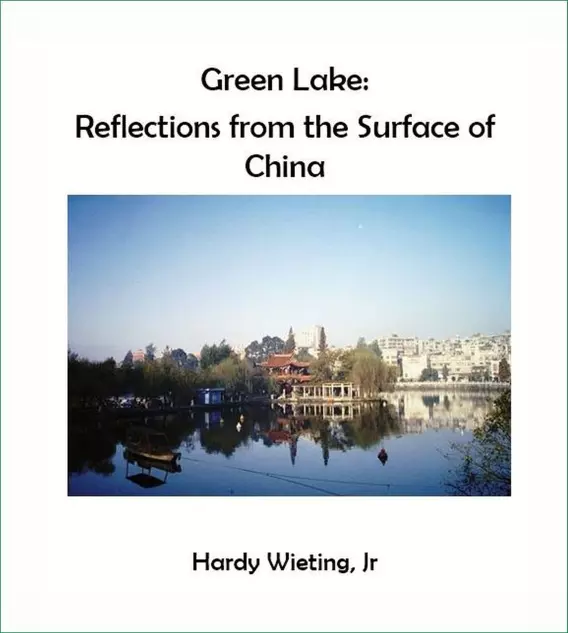

Down the concrete-tiled pedestrian lane to our right. This leads to Kunming's small but famous Green Lake, past vendors who wheel their little carts here every morning to sell vegetables and rice noodles. One woman is toasting Chinese tortillas on a pushcart charcoal grill. She tongs one off the grill, spreads bean paste and red pepper paste onto it, and hands it to a paying customer. Below us we see: one corner of the lake; the elaborate white railing made of carved stone that circles the entire lake; the three-arched white-stone bridge that leads to the central island; and the wide white sidewalk made of carved stone tiles that follows the railing and which like most everything in the city is a little grimy from dust and constant usage. It is sunny and somewhere between cool and warm, in late November, at about 8:30 in the morning. The air is clean, and the sky is blue.

We cross the busy one-way street that circles the lake and turn to our right so that we can circumnavigate in a counterclockwise direction. A dozen ladies in their 70's and 80's are there following a leader in simple bending and stretching that includes stylized patting of ankles and thighs with both hands. The entire lake complex is a large exercise arena in the morning, though jogging is not one of the forms of exercise to be seen (a friend claims there are some joggers, but they're out before the sun rises, to avoid the people).

After passing the west gate to the island, we walk to the side of and past some badminton players -- rarely a net, just hit the shuttlecock back and forth. There is also badminton in front of the impressive Jiangwutang, the Yunnan Military Academy: the two-story building is almost a block long on each side, a very large square surrounding a very large central courtyard once used for soldiery parades. The ocher façade, the red-tile roof, the Spanish-style main entranceway make the building look more like something that belongs in Mexico City than in Kunming. There are two roof-to-ground black-and-white photos hanging on one corner of the building, advertising an exhibition of late-19th, early-20th century photos by the French consul, Auguste François, which were discovered in a museum in France. One photo is of a warrior in leather armor, the other of a young noble woman.

Twenty women in their fifties doing tai chi are ahead of us. Twenty more are doing (I think) qigong, which involves the use of red fans snapped open and shut dramatically at the far end of a long slow extension-contraction of body and arm.

Then twenty more -- grandmothers with swords. There is a sight! They are performing a routine similar to the ladies with the fans. The swords are made of metal, and they are used in a wide sweeping motion. The skill must be in not slicing the grandmother next to you.

Forty more women and men doing tai chi in unison. And other groups beyond them. A little further on about a half dozen couples dancing to ballroom music played on a small tape player. (In the 60s, this sort of dancing was said to represent a “corrupted capitalistic lifestyle,” inconsistent with the ideology of class struggle.)

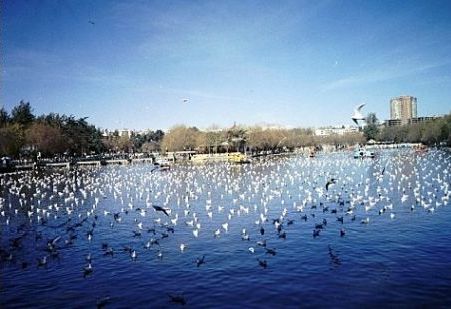

It is late enough in the month that the Black-headed gulls have arrived on their migration from Siberia. There are several thousand of them. Green Lake is ready for them, with "seagull bread." This is sold by vendors all around the lake. People tear off pieces of bread and, standing next to the stone railing, facing the water, toss the pieces up into the air. The seagulls, whose flocks fly continuously around in a great circle formation, first along the railing and then out over the water and back again, catch the bread -- acrobatically. This goes on all winter.

Out on the lake, there are fleets of foot-paddle boats, odd looking and in no way Chinese. They look like large toy plastic automobiles, sans doors. In an interior bay, accessible only from the island, there are small motor boats for kids that resemble submarines. Mounted at the front is a laser gun. The parent steers the boat, and the child aims the gun at mines laid in the water. A direct hit causes the top of the mine to spout water in several directions.

Following around to our left, we encounter a couple of sweeper ladies in their light turquoise-green sleeveless jackets, soft white caps, and surgical masks. They carry a broom and a dust pan in one hand and what looks like a very long pair of scissors in the other -- used for picking up things. Actually, they are upper echelon sweepers, as far as I can tell. The heavy sweeping is done by men in orange cloth vests who use a large Hansel-and-Gretel broom.

China works on the “drop-it-anywhere” principle. There are plastic trash containers attached to metal posts at regular intervals, but as many plastic wrappers and bags are just dropped on street or sidewalk as are placed in those containers. (Everything here is wrapped in plastic and carried home in small plastic bags). One trash container is orange, the other green; no one seems yet to have figured out what goes in which.

Actually, China works on the "drop-it-anywhere, sweep-it up-tomorrow" principle. Judging by Kunming, all of China is a pile of trash by midnight, swept clean every morning. Two lovely young women sweep our apartment complex every day, using the large Hansel-and-Gretel brooms. The teams of sweeper ladies at the lake pick up everything dropped around the lake the previous day. In addition, all eating places are swabbed every morning with a wet mop, as are most shops, though this is for dust rather than for trash. Anything dropped in the lake is dealt with by men with wide-brimmed straw hats who pole flat boats around the lake and fish refuse out with nets attached to long poles.

The crowds thicken as we come to the next gate, the main gate leading to the island. Actually, there is no island. It is more like a union of peninsulas that project out into the middle of the lake, parts of which are accessible by bridge, parts by a wide walkway. Here at the gate there is a wide walkway leading onto the "island."

* * *

Let's stroll through the gate. This is the wide walkway, a handsome avenue full of people, lined with plants in ceramic pots. Further ahead there are many weeping willows.

We reach a series of Chinese pavilions and Chinese gates. Through one of these, on our left, there is a series of large carp pools with many gray fish, and a few orange and yellow ones. People stare down at the fish, and the fish stare up at the people, waiting for them to throw crumbs of bread into the water. A covered walkway beside one of the pavilions is filled with people listening to small groups of older men playing the erhu (two-stringed Chinese cello) while women "accompany the sorrowful tunes with their tremulous voices," according to one guide book. One of the peninsulas has a series of working greenhouses on it where the plants that stock the whole area are grown. Large portions of the island seem always to be under construction, laying in some new underground pipe or reconstructing a sidewalk. The muck dug up for this is black, very unlike the dark rust color soil that we see everywhere else.

The island is as crowded as the circumferential walkway, if not more so. The same sorts of exercises, and feeding of gulls. There is an area planted with banana trees. Another with a sort of topiary hemisphere. There are a few modern sculptures dotted around the island.

* * *

Back out the gate we came in, we turn to the left to continue our journey round the lake and almost immediately come to Dicos, a KFC knock-off with a large play area for kids upstairs. Then several more restaurants, one a Dai restaurant with a menu in English. Like Dicos, all these restaurants jut out onto the "island" and some have rear patios that overlook the lake. To our right, across the road, apartment buildings with shops and restaurants on the first floor. Also the Kunming Youth Hostel, where (so says the guide book) a decent room can be had for $2 a night in this posh area.

Beyond the Dai restaurant, we see the lake again. The vastly larger lake next to Kunming is Dianchi (Lake Dian). About 600 years ago, the waters of Dianchi came up as far as our park here, until in the Ming dynasty reclamation projects reduced Dianchi's size substantially, leaving here a remnant that is now Green Lake (Cuihu). It covers an area of 15 ha.

There are, incidentally, a little over a million Dai people in Yunnan. They are known for their agricultural talent, which accompanies their preference for fertile river basins. They build their houses on stilts and fence in livestock on the open first floor. They are Theravada Buddhists; every male serves as a novice monk for a month or so in his teens, although most do not continue as such. "Most of the men have tattoos. Women wear tight tank-top-like shirts and sarongs. Their long hair is rolled in buns and neatly tucked behind their heads." Other minorities in Yunnan include the Zhuang, Bouyi, Shui, Yi, Bai, Hani, Lisu, Lahu, Naxi, Jingpo, Tibetan, Pumi, Nu, Achang, Jinuo, Mongol, Dulong, Miao, Yao, Wa, Bulang, De'ang, and Hui.

Our American friend, Hoa, tells us there is a saying here that "the mountains are high, and the emperor is far away." This helps account for the persistence of so many minority groups (at least one-third of the province's population, on two-thirds of the land). The history of the province is one of conquest and revolt -- revolt sometimes by the same people who were the conquerors. A good example is Wu Sangui, who is associated with Green Lake; it was his "playground" when he ruled this area of China. General Wu has a fascinating story.

Three years after the suicide of the last Ming Emperor in 1644 and the ascendancy of the invading Manchus (who established the Ching or Qing dynasty), one of the Ming heirs proclaimed himself Yongli Emperor of the Southern Ming. He considered Yunnan to be within his realm. Many strongmen rallied to his side. Secret societies also joined. The most famous of these was the Tiandi Hui or Heaven and Earth Society. (The Chinese mafia, the Triads of today, claim roots in these societies). In 1658, the Qing sent General Wu to crush Zhu, the Ming heir. Wu himself had gone over to the Manchus when they invaded China. With the help of Southern Ming defector generals, "Yongli's head fell to Wu's blade." Many southern generals fled to Burma, but Wu intimidated Burma's monarch, who handed them back -- more heads fell. The Qing bestowed on Wu the title of "Great Pacifying King of the West." He received Yunnan and part of Guizhou as a fiefdom, and allied generals received their own fiefdoms in Southwest China. Together they were the Three Feudatories. Soon their tribute to Beijing became mere lip service. The mountains are high, and the capital is far away. The Qing revoked the titles. The Three Feudatories, led by Wu Sangui, rebelled. In 1681, after seven years and three years after the death of Wu, Emperor Kangxi (age 16) finally put an end to the rebellion.

This is a corner of the lake I call the Lotus Pool, because, of course, it is filled with lotus plants. A few are now in bloom, but it is too late in the season and the leaves look wilted. The walkway widens, and the trees which have been marching around the lake with us change from eucalyptus to some sort of locust. The base of every tree, to about waist height, is painted white. The walkway now narrows. We pass a man rotating stainless steel billiard balls in one hand. Further on is a gray-haired beggar who may or may not have legs below the knee and who spends his entire day bent forward with his nose two inches from the sidewalk.

Across the road, on our right, is a series of prosperous looking establishments: Fennel Pub; Coffee, Wine & Tea; Green Lake Tea Room. And Yunnan Tobacco, which vends the local product. Beyond them is the construction area where the old section of the Green Lake Hotel used to be (they tell me); further back is the new section of the hotel, about fifteen stories tall. Soon the hotel will have a new section and an even newer section.

A road here goes off to our right. Two blocks out, past the skyscraper for the Yunnan tobacco conglomerate, past a Buddhist temple, past the zoo, there is a starkly modern suspension bridge -- a single pillar in the middle of the bridge with suspension cables down to either end, and then more cables down the middle, dividing the two lanes going back and forth across river. The whole structure forms an attractive triangle.

The bridge is over a river that is now really a canal. The water is polluted and not very deep, though the stone walls holding it in are tall. Along the river is a wide pedestrian park. Just a few years ago this was an area of old one-story houses and narrow lanes, "the old city." The area was charming enough for Zurich, which has its own old city, to enter into a sister-city relationship with Kunming. A crisis was created in far-away Switzerland when the old city here was all torn down.

Most of the cars going round the lake go off on this road, and over the bridge, headed for downtown.

* * *

Back to Green Lake. The street circling the lake narrows and now has mainly bicyclists. This reminds me that a friend of mine once saw in the Green Lake area a bicyclist he calls "the chicken man" because he was riding along with live chickens suspended from his neck, and the handlebars and every other part of the bicycle, so that he appeared to be one large chicken on bicycle wheels.

We pass another gate and then another Lotus Pool. Thirty dancers, mainly women but some men, dancing in pairs to ballroom music, tangos and fox trots. The far end of this pool has a small dike made of sandbags. The sandbags end at the peninsula of working greenhouses, off limits to everybody but workers. It is here that I see birds, if I am going to see them at all. There is a black and white wagtail that is common throughout the area, but I have also seen a tiny kingfisher -- once.

Then a performers plaza, a large area consisting of three or four concentric circles, each one smaller than the last, which descend below the surface of the main walkway, creating a series of steps people can sit on -- a sort of amphitheater. Today the center is occupied by about sixty five-year-olds from the school across the street following a leader in morning exercises and dances.

Here the trees cha nge back to eucalyptus. We are about three-quarters of the way around the lake at this point. The street to our right here departs from the lake and goes out towards the main gate to the city's oldest university. A walk through there leads to a street which gives access to three other universities. A little further on, our right side is now hemmed in by a wall surrounding a large complex of apartment buildings that face the university.

We pass another man rotating metal billiard balls in one hand, this one walking backwards. A group of thirty woman doing qigong, I take it, with castanets, large red castanets. Another ten in a different group using large red fans. We pass an older man in a Mao jacket. On our right, apartments overlooking the park. On our left, across the open water is a round concrete platform at water's edge which is a sort of mini-Bellagio -- not the Bellagio in actual Italy, not the one on Lago di Como, with the Grand Hotel Villa Serbelloni, but the one in -- Las Vegas. The one with the famous dancing spurts of water. This one is much smaller, but nevertheless impressive, with sky-high streams of water pulsing out into the sky to the rhythms of the toreador theme from Carmen or a Souza march. The waters are still now, in the morning, but on the weekend, people stand around the platform and watch the show, trying not to get wet during the grand finale. A couple of teenagers run back and forth through the jets of water, thoroughly enjoying getting thoroughly soaked.

Now a broad plaza, with another gate to our left. We walk to the right of an elevated area planted with grass and shrubs. There's a handsome gray building in vaguely Spanish style on the far right where you can get something to eat. This whole grand area is filled with people -- exercising, dancing, flying kites so high they’re almost out of sight, playing badminton. One or two are smoking using a large, yard-long metal tube; mouth and jaw go in the upper end, and a cigarette is planted in the tip of a small, thin pipe jutting out near the bottom. There is a children's play area next to the near end of the building. There is a square of tamped-down sand for croquet at the far end of the building.

We pass an old man carrying two bird cages. The cages are covered with olive drab cloth covers, black tail feathers sticking out. He takes his Crested Mynas out to the lake, walks with them out to the center of the island and hangs them on a branch, for some fresh air and sun -- in their cages, of course.

Also, a three-year-old girl with her grandparents. She is toddling along wearing a knit cap that has two shoulder-length dark blonde curls sewn onto it, one on each side of her face.

We are now back to the street, and to our left we can see the end of the pedestrian lane where we started this walk.

* * *

The only thing left to do is to come back and see all this at night. The whole area is lit up, neon lights outlining the rooftops of the pagodas and the pavilions, halogen lights illuminating the bridges and surrounding walkway, and spotlights liberally sprinkled among the vegetation. It's beautiful.

* * *

What about Kunming in a broader perspective -- and China -- what’s it like being here? It is of course utterly preposterous to say this, but our first impression is that China has a lot of people. A billion people, several hundred million more than a billion -- certain primary facts, like a dirigible in a tunnel, occupy the mind when first in mainland China. There are just lots and lots of people walking on the sidewalk with you, and in any direction you cast your eye. “A private moment,” “all alone,” “not another soul” are phrases which suddenly seem distant.

You are particularly aware of this if you have, as we have, brought your dog half way around the world with you. Imagine trying to find a place for your dog to go while people are streaming past in both directions, day and night, and you feel conspicuous, being the only Westerner in sight. People are watching, and curious -- the only dogs they regularly see are little yappy Pekinese, and this long-nosed American with his large wolf-like dog is wearing a plastic bag on his hand, as if it were a glove. At least our dog has a Chinese name, Shanghai.

It is very tough to find anything other than concrete beneath your feet here in the city. Imagine our relief (and Shanghai's) when after several days in our new apartment near Green Lake we discovered that that old French Legation/Military Academy (now a museum and some sort of school), has an extensive, though thin, strip of vegetation between the sidewalk and the wrought iron fence along its front. Never mind that this grassy strip is studded with foot-high shrubs, so that Shanghai has to weave in and out as she makes her tour: it's sufficient.

* * *

Although we are now all, including dog, safely ensconced in our own apartment in Kunming, this has been one of the most hectic periods of our lives.

The actual travel half way around the world was the least of it. First there were the shots (recommended for extended stays, but not required) -- hepatitis, typhoid, tetanus, etc. Then the drive across the US. A California interlude was spent mainly trying to figure out the requirements for importing a dog into China. Hong Kong, where we would stay for several days before going on to Kunming, has complex and onerous requirements for landing your animal there, but at least they are out there on the internet and actually followed by the bureaucrats. No hotel in Hong Kong will take a dog, so Shanghai had to stay at the kennel, which is run by some Brits. The kennel is way out in the country (Hong Kong is bigger than many think), and we spent a good deal of time visiting her out there, when we weren't changing hotels and visiting old friends and changing money. Even with Hong Kong there were some confusions: the kennel suggested that before arriving we implant a microchip in Shanghai, as one less trauma she'd have to undergo after a 14-hour flight. We had a vet in California implant such a chip. When we got to Hong Kong we found they use a different system; Shanghai now has two microchips in her.

The requirements in Hong Kong center on a "special permit." No one knew the requirements for Yunnan Province, beyond the fact that they would want proof that the dog had been vaccinated against rabies. The airline we were flying on, Dragonair, said they don't take dogs. (I then crossed Dragonair off my list for all subsequent flights, with or without dog). We finally persuaded China Southern Airlines, in the very able person of Coleta Wong, to ship Shanghai as cargo without having an import permit, on the grounds that nowhere was there a published rule that you had to have such a permit. When we actually did get to Kunming, all of our time for the first few days was spent dealing with the dog.

When we landed in Kunming, for example, we made the mistake of going with our hosts to the guesthouse near our university to drop off our bags. Shanghai-cargo was not due to arrive at the airport for about two and a half hours. But we got caught in rush hour traffic near the university and then again, even worse, on the return trip to the airport. Customs people had left by the time we arrived back. We had to search the airport cargo area for our dog! At least we succeeded in finding her. Poor Shanghai was in her carrier in a corner just outside the cargo area adjacent to the airport. The man there wouldn’t let us take her home, but he did allow us to let her out of her cage for a short while. We gave her water and a little something to eat. Next day we had to find the Department of Entry/Exit Inspection and Quarantine and the appropriate officials who deal with this matter. This agency manly deals with importation of livestock. Once we found the right people, they were wonderful, as were others who worked there. With their help we eventually secured Shanghai’s release and took her back with us.

We were housed at the guesthouse for the first ten days. Our first night there was especially memorable, and not just because we were separated from our dog. As we settled

in, we noticed an odd gizmo on the bedside table;

it looked like you could plug it in and somehow use the little packets that came with it. We paid it little attention. The evening was hot, so we opened all the windows to get some fresh air before retiring early to our beds. It was then that we came face to face, literally, with a basic fact about Kunming: mosquitoes that emerge when the sun goes down, attack mosquitoes. The windows lacked screens. “Closing the windows after the mosquitoes are in” is an even more potent expression of futility than that one about horses and the barn door. We had a miserable night. The next day we learned that the packets contain mosquito repellent which the gizmo ignites and holds.

Money matters took up a great deal of those ten days and continue to occupy a disproportionate amount of time and effort. No one pays for anything with credit cards here; it is a cash economy. This has entailed, then, getting advances on credit cards. Only the main branch of the Bank of China, downtown, gives such advances. I had the problem that my MasterCard is so well-worn that the signature is obliterated. Try getting an advance with an obliterated signature. We are getting to know the tellers.

* * *

We also were busy dealing with the issue of what school our daughter Alex would attend. She is going into the second grade. Although everyone recommended Yunnan Normal University's primary school, just up the street from our apartment, we had to go there several times to persuade them to let this little American girl in who does not speak Chinese and who cannot read Chinese characters.

Finally, the head of school said he was deeply moved by our wish to have our daughter become acquainted with her heritage and learn Chinese, so she was in. Pay 2,000 yuan (at about 7 yuan to the dollar). Then we worked out a deal where she goes to the morning session (8-12), and we have a tutor in Chinese for her for the afternoons -- at least this is the deal for now. We also had to persuade Alex this was a good set up. She was very reluctant to go on the first day -- "But I won't understand a word they are saying!" Eventually, however, she agreed to do it. Now, about two months later, she looks forward to school every day. She has made friends with the girl who sits next to her (there are 70 students in her class). She likes the exercises they all do in the school yard, and the fact that they have English every day -- on the first day the teacher asked her to read a long poem to the class. “Very boring poem," said Alex.

We have made a friend here whose adopted daughter, Emma, is five. They came about a year ago, and Emma started in pre-K. It took Emma about five months to start speaking in Chinese. Apparently younger children can sometimes be more reluctant to throw themselves into a new language than seven- and eight-year-olds.

Then there was finding a place to live. This involved looking at a number of places of all descriptions. It also involved meeting a very nice young American named Hoa. He is partly of Cambodian heritage and was in refugee camps, but came to L.A. when he was a young child and grew up there. He went to Oberlin, majored in philosophy, then went to Columbia in Chinese Studies (he already spoke Vietnamese, Khmer, French, and something else). He came to Kunming as a Shansi Fellow; Shansi (headquartered at Oberlin) is one of the oldest educational exchange institutions in the US. He then married a Chinese; they have a boy now age two. (Hoa's own father was a mathematician in SE Asia, then worked as a chef in a Los Angeles restaurant; his father, Hoa's grandfather, living in Cambodia at the time, could see that the Khmer Rouge would win and decided the family should flee -- a wise man who saved his family.) Hoa helped us deal with the real estate agents and the owners.

We ended up very near Green Lake and Alex’s school, in an apartment that has two bedrooms, a den, and two bathrooms. We are on the fifth floor; the building is fairly new. The hot water supplied by the tank on the roof is irregular, so we have installed a water heater above the shower in the master bathroom. During the winter, China (all a single time zone) is thirteen hours ahead of EST.

One of our first free moments was the Autumn Moon Festival, and Green Lake turned out to be a wonderful place to celebrate it. We learned that this ancient festival, which occurs during a full moon on the 15th day of the eighth month in the Chinese or lunar calendar is a harvest festival that dates back, in some form, perhaps to the 16th century BC. The Tang dynasty was much later (618–907 AD), and that is apparently when it really became widespread. We walked around the lake, in the dark, along with thousands of other people. Shanghai was with us. The moon was out and full, of course, reflected in the lake. Mooncakes are given and received during the festival. Mooncakes are essentially a circular lump of bean paste encased in pastry that has a Chinese design on top. Yunnan has a distinctive mooncake of its own known as a t'ou, made with a crust which is a combination of rice flour, wheat flour, and buckwheat flour. Lanterns, too, are associated with the festival. We saw many adorable kids carrying red and green lanterns with candles in them. Just as many had those bracelet/necklace rings that glow in the dark. Shanghai was a big hit with everyone we passed, especially with young couples and children: seeing a wolf coming at you in the dark is quite an experience, though everyone caught on very quickly that this wolf was very friendly.

* * *

We’ve spent a great deal of time taking the necessary steps to obtain a residency permit. The visas we were issued in Washington provide for only one entry to China, as tourists, but there is a note on them that says once we get a residency permit, these can be converted into multiple entry visas used by resident experts and families. Obtaining a residency permit involves, among other things, having a medical exam at a clinic way across the city. All went well there until we got to the chest x-rays -- the machine was broken. Come back on Monday. On Monday, we were told that the father of the technician who gives the x-rays had died on the weekend. It took them some time to find a substitute technician. Our passports were then out of our possession for about two weeks in the office of some bureaucracy in Beijing. Eventually I picked them up at one of the offices of the university's Department of Foreign Affairs, which has a pennant from the University of Illinois hanging on the wall.

Our host here, whom I refer to as "my professor" is one of the nicest people I've ever met, as is his wife. We've also been working with three of his grad students. My professor wanted us to try the local specialty, so he and his wife took us to a restaurant to get Crossing the Bridge Noodles. The story behind the name tells what this dish is. There is married man deep in study in order to pass the imperial examinations and become a mandarin. In order to isolate himself from distractions, he has located himself on a little island. His wife brings him food, but she finds that the noodle soup is cold by the time she crosses the bridge. An inventive lass, she obtains a large earthen pot and fills it with boiling broth, topped by an insulating thin layer of oil, keeping the noodles and meats and vegetables in a separate container. Now she adds these to the still boiling broth when she arrives. There are other versions of how the name arose, but this is the romantic one. The restaurant we went to is famous for its CBN. A platter containing very thin slices of uncooked meat, vegetables, and the rice noodles accompanies the big bowl of boiling broth. You quickly combine all this and wait for the broth to cook everything and then cool down a bit. Delicious.

Other superficial impressions: The streets are defined by apartment blocks of six or seven stories, arranged in an unvarying grid. On the street floor there are no apartments, just shops. From the second floor on up, however, each apartment has a compact, cage-like balcony protruding over the street -- here clothes are hung up to dry, plants are kept and watered --- watch out below when that happens. On the sidewalk it is shop after shop: sundries (mainly cigarettes), clothing, restaurant, fruits and vegetables, bicycle repair, food, another food, rental agent, mattress factory, sundries, restaurant, pots and pans, camping gear, food, barber, dumplings and noodles, butcher, shoes, tea shop, Chinese medicine, acupuncture, food, Korean restaurant, food, plastic goods, office supplies, butcher, sundries, restaurant, food, and so on, ad infinitum. The shops are often wide open to the passerby, the only door being a pull-down metal garage door to lock up at night.

The main streets have sidewalks filled with streams of pedestrians who have to navigate around the people standing in front of the shops, streams that include peddlers (long bamboo stick on shoulders from each end of which hangs a wooden square stocked with some, usually plastic, item) and beggars, and bicycles and motor scooters -- to say nothing of another stream coming in the other direction and cars exiting and entering driveways. Beyond the sidewalk, on the edge of the road, is a layer of street vendors: tangerines, bananas, omelettes, satays, roasted potatoes, coat hangers, vegetables, goldfish in bowls, purses, grilled corn, cotton candy, etc. Another layer of pedestrians on the roadway, passing in front of the peddlers. On side streets pedestrians walk in the road, and this whole scene is compressed into an even narrower space. The sound of honking cars and small Changhe vans attempting to navigate through the people is frequent and loud.

Dress: the vast majority of people are indistinguishable, in terms of dress, from people anywhere else in the modern urban world. This is particularly true of younger people. Among the old there is the occasional Mao jacket. Later I was to ask numerous friends whether they thought the persistence of this form of clothing was a political statement or because the person was too cheap to buy something new. To a person they answered: cheap.

Traffic: at five, everyone with a car leaves work and pulls out into a street full of cars going nowhere. Gridlock is a general condition downtown, since Kunming lacks a subway. Some major streets have a separate bicycle lane, but in many streets bicyclists compete with cars for the edge of the street.

Food: There are a thousand things to say about food. Spicy. Eaten continually and often on the run. Or eaten in a small place wide open to passersby that has a few tables and a couple of woks. Rent a shop, fire up a couple of woks, put out some tables on the sidewalk -- you have a restaurant, like all the others on the block. For eating on the run, particularly with the students at the university, a large round enameled bowl-sized cup is particularly popular -- a large scoop of rice goes in there, with stir-fried vegetables-and-meat crammed down on top. One eats (usually with a spoon) as one walks along, talking to one's friends. In a restaurant (with a door), one does not mix the rice and the stir-fry meats and vegetables -- eat some stir-fry either right from the serving dish or by placing it in a saucer-sized plate held up to your mouth, then have a bite of rice. Shredded pork with vegetables in the US is not too different from shredded pork with vegetables in Yunnan Province. Shredded potato stir-fried in chili oil is as good as French Fries. Food is everywhere, vegetable markets are everywhere, meat markets are nearly as prevalent. “The Market” -- every time we asked where to get something, that was the answer. The Market turned out to be a whole street, the middle of the street as well as the sidewalks. Outdoor tables everywhere, covered with an astonishing variety and abundance of things and vendors. Clothing, plasticware, kitchenware, bathware, furniture, cakes -- you name it. Most astonishing is the butchered meat out in the open air, cut with cleavers, on plywood tables washed down each evening.

Then there is mi xian, freshly-made rice noodles in broth, here a version distinctive to Yunnan. When you get tired of stir-fry veggies on rice, try this bowl of rice

noodles and veggies and scallions and peanuts and a few pieces of meat in a broth spicy with red pepper paste – delicious! Or try one of the many, many street vendors: kebabs,

Chinese tortillas filled with spicy bean paste, potatoes on a stick, smoothies made with fresh watermelon or pineapple, pork fat grilled with a dusting of red pepper, roasted corn and

yams. Italian food is very popular, especially among the young, though in restaurants not on the street. We eat at Teresa's Pizza, at The Box (just opened by some of our friends, two

Italians, two French, an American and his Chinese wife), at the French Cafe, and at Rocco da Pizza (Rocco is Italian, his wife Chinese) -- all have good pizza and pasta. Beer: the local

beer is Dali, named for one of Yunnan's major tourist destinations. A thousand teas in a thousand tea stores. One tea fermented for a hundred years. Wine: there's a Yunnan red, and

wine from other provinces, of which the best is from Shanxi province; Australian wines are available and good, and three times the price of the local product.

What is responsible for all this food? The productive power of modern Chinese agriculture? The Green Revolution? Mechanization of the farm? The cunning of the peasant? Soils fertile for thousands of years? Answer: maybe the one-child policy.

Smiles: the merest attempt to communicate -- simply a wave or "hello" -- with any child or young person elicits the most wonderful smile. Sometimes a bashful smile; sometimes a beaming isn't-this-wonderful smile. Even older people brighten noticeably and return a smile.

Wealth: if a country's wealth is measured in the industriousness of its people, then China is one of the world's wealthier countries. Everybody, it seems, works all the time, morning, noon (save for a lunch break), and night, seven days a week. Banks are open on Sunday. Tearing down the old, putting up the new, carting things around, selling things, buying things, cooking things. If political catastrophe can be avoided, development will proceed apace. China will become rich: an idea of awesome consequence. We haven't seen the countryside yet.

Our university: it is just like Kunming, and the other university's nearby, busy tearing down the old, putting up the new. There's one handsome old building in Western style (would be at home at Harvard) that they've been renovating night and day since we arrived; it is not far from what used to be a huge hole in the ground and which now has an enormous frame of steel girders overseen by a sky-high construction crane. Down the way is a very large new classroom building which just opened; the old buildings in front of it were torn down in front of our eyes. The center of the university, between the library and a science hall (built by a US Malaysian of Chinese descent who made a fortune importing tobacco into the US) is a large courtyard of basketball courts -- in constant use. (There are plenty of six footers among the students). The building, where I have my office, is in the North Campus, across a busy avenue from the main campus. Almost bunker-like, it is nearing the end of its useful life, and was not attractive when new, but I am growing fond of it. It is near a large complex of student dorms and cafeterias, where I can get a lunch of rice and stir-fry or noodles in spicy broth for a quarter, at most.

Another glory of being in China, for me, has been to see these young students every day, thousands and thousands of them. It is tempting to read deep thoughts into their attractive faces: where am I going? what's going to happen to me? Undoubtedly the real thoughts are more worldly.

Now that we are settling in a bit, I can report that the highlight of my day is the walk up the street with Alex each morning to send her off to school. This involves crossing a street right in front of the school that is an absolute madhouse of vehicles and parents and children all trying to go past the same place at the same time. There's a traffic cop who has no effect whatsoever. Basically, it is dodgem as we squeeze past cars and bicycles (I worry about the buses). Once through that we are at a short driveway that leads up to the main gate. An honor guard of fourteen students is there, seven on each side of the driveway. They are in uniform, with a bright red sash from shoulder to hip. (The school has uniforms for each grade, even classroom, rather than a common one for the whole school, but these are not worn every day. Many of the uniforms are based on the dress of one of Yunnan's ethnic minorities -- the effect is very colorful). The girls today are wearing pink shoes, white tights, a short dress with a dull flower print, a light blue denim jacket with a sailor's collar, and one of those blue elastic things that you put around a bun or pigtail. Children are streaming past, all with back packs, all bent forward with their arms straight down while their little legs propel them forward at a run. Each one is totally an individual despite the uniforms. Parents are dropping kids off from motorcycle, bicycle, car. Each time the honor guard sees a teacher, one of them shouts “Lijian qi lai” (literally “Raise your sword”}, then all swing their right arm up above their head and shout "Lao shi hao," which means something like "Greetings, teacher." And in Alex goes.

There are a million adorable kids in Kunming alone. They all like to say "Hello!" when they see us. Some of the very young ones, who can’t speak yet, wear pants that have no crotch. Saves on diapers. Try to imagine a child like this riding in a shopping cart at Walmart! Yes, there is a Walmart. Try to imagine all of Kunming compressed into one building -- that is Walmart. It is difficult to turn around. People with megaphones hawking the latest gizmo or the best deal. A French competitor, Carrefour, has just opened its doors further up one of the main streets, and has been similarly mobbed. They like massage in Kunming. "Professional Blind Man Doctor's Massage Clinic." I was chuckling over that one when I noticed, a few doors down, "Woodpecker Professional Blind Man Medical Treatment Massage Room." All the newer sidewalks have a line of special tiles that are easy for a blind person to follow; I have never seen a blind person following it. Kunming is not even the most interesting place in Yunnan, they tell me. There's Old Dali, imperial metropolis (738-902 AD) of the Nanzhao, a multi-ethnic kingdom dominated by the Yi, and then later the Bai, who were eventually defeated by Kublai Khan; traditional square stone houses, fortress walls, pagodas -- all this preserved, next to sea-sized Erhai Lake, for us tourists. There's the old city in Lijiang, wooden houses, canals, ruled by the Mu clan for nearly 500 years (until 1723), home of the Naxi culture, beloved of Joseph Rock, the Austro-American botanical personality who was supported by National Geographic. Deqin, entrance to Tibet. The Burma Road. Xishuangbanna, tropical, center of the Dai people (relatives of the Thai). Tiger Leaping Gorge, one of the world's deepest gorges.

China is its thousand teas. You can sample a few, but it would take a world of learning to know them all, or even a majority. Fascination hardly does China justice. Everything so similar and so different. How ugly, how beautiful. The eye is constantly busy. It can be tiring. The mass dissolves quickly into individuals. A heap of wonder. I wonder how this got there; I wonder why they do that; I wonder what his story is or hers. (Reading Wild Swans by Jung Chang -- which I have heard described as the best-selling book in English ever written about China -- is a good start).

October 1, National Day. The final victory of Mao over Chiang and the hoisting of the red flag over Tiananmen Square in 1949. No fireworks, today, few red flags in Kunming. The normally traffic-choked streets are now an easy drive, though. The airport is efficient, as is China Yunnan Airlines, with its brand spanking new Boeing 767's. I am on my way to Beijing because from there I will fly to Central Asia for a week to see an old friend. The clouds clear halfway through the three-hour flight; below is nothing but barren mountains. The last time I saw Beijing was from an altitude of 35,000 feet on a crystal-clear day in the first week of January 1996 -- the city covered with a blanket of snow -- when we were on our way to get Alex. We overflew the national capital and landed in Hong Kong, eventually making our way to Hunan province.

October 2, Beijing, at the Airport Garden Hotel, killing time waiting for my flight to Central Asia at 23:10. Some hotels, even in Kunming, have a few western channels, but this hotel doesn't, though it does have about 50 channels and some good stuff. There is an entire hour filled with newsreels of National Day parades in Tiananmen Square from the 1950's and 60's. Mao Zedong, Ho Chi Minh, Chou En-lai doing their best to be on display – even, from the days before the Sino-Soviet split, a glimpse of Khrushchev. What once was boring is now fascinating. Tons of military gear, thousands and thousands of soldiers, other young men and women in drill formation waiving things. The practice petered out and then stopped after the Great Leader died, the documentary indicates. (The CCP General Secretary still reviews the troops, however). This foray into China’s recent history is then followed by a big-budget film about the mid-Seventeenth century battles between the Ming and Qing Dynasties, and the ultimate recapture of Formosa from the Dutch. Subtitles in English. The film is The Sino-Dutch War 1661 by Wu Ziniu, a member of the famous “Fifth Generation” of Beijing Film Academy graduates (of which the best known is Zhang Yimou). Many Hollywood touches, such as the love story between the son of the Ming Emperor's Commanding General and a Buddhist waif found by his mother on a beach. The dialogue includes sexy interchanges between the two principals, such as one that ends with “Thank you, Imperial Name-keeper.” There is also the scene of a final battle to oust the Dutch from their Formosa fortress that compares favorably, spectacle-wise, with anything done for the Invasion of Normandy.

The night before there was a broadcast of the National Day concert from Orchestra Hall in Beijing, the Central Committee in attendance. The Hall is decorated in red. I tuned in at the conclusion of a piano concerto, featuring a western pianist. This was followed by Chinese music of an operatic nature and a most interesting soloist, a singer, a strong-voiced boy dressed in a Chinese coonskin cap, tiger-skin vest, white ruff, dark jacket with fur-covered collar -- his face painted as for the Peking Opera, and his expressions to match. His lengthy aria was interrupted several times by applause. The music was traditional and enchanting. I enjoyed it immensely, though I had no idea what it was -- if I had to guess I would say it was from one of the operas based on the Three Kingdoms saga (the title used to be translated into English as The Romance of the Three Kingdoms).

When I returned to Beijing from my Central Asian excursion, Susan and Alex flew up to meet me. We had to get Alex's passport renewed before it expired in November. This was one of the things it would have been far better to do in Washington before we left, but for all the other things we had to do. On our first day together, we made our way to the war zone that is the embassy row of the capital of China. The whole area, several city blocks, is surrounded by crowd-control barriers. There are Red Army guards on every corner. You show your passport to one set of guards at one corner, then walk down a completely empty street one block to the next corner where another set of guards -- who saw you go through the previous set of guards -- examines your passport carefully. On to the next corner, and so on. We eventually turned a final corner to the front gate of the US embassy, where we encountered a phalanx of guards in black SWAT team uniforms who rushed down to meet us. They were Chinese who work for the US. Quite friendly. They told us that today was Columbus Day and the embassy was closed.

We headed off to the Forbidden City. We passed under the giant picture of Mao, paid our admission, and rented the audio tour cassette. The narration on the tape was by Roger Moore, James Bond #2, not someone who would spring to mind, perhaps, when one thinks of the Last Emperor or of Mao Zedong. But he is amusing. We have all seen this palace complex on television and in the movies a hundred times. It is overrun with tourists, mainly in groups led by a guide holding a flag. There are signs of wear and tear here and there. Many of the individual structures burned down at some point and were reconstructed. Despite this, it is impressive. There is a flow of tourists from the South Gate to the North gate. You are swept along from palace to palace, each as elaborate as the next. No one thing stands out in my mind, but there are many interesting details like the little group of figures found on the corner tiles of most of the roofs, a man riding a hen followed by dragons and other figures. There is an elaborate, though compact, garden in the area just inside the North Gate. I actually know someone here in Kunming who stayed there overnight. He just stayed in a corner while everyone exited and the guards locked the gate. I suppose this was possible because the Forbidden City is no longer a political institution but a museum.

We got our daughter's passport renewed the next day, but by the time we had gone through all the required rigmarole, it was too late to take the bus out to the Great Wall. We toured Tiananmen Square and tried to imagine 1949 and then what happened there forty years later. At the end of the afternoon we took one of the bicycle rickshaws (most are small motor scooters, the guy who cornered us uses a bicycle) out to the Temple of Heaven, which proved to be much further away than appears on the map. It did give us a good look at some of Beijing away from the main tourist areas. We arrived just as the park the Temple is in was closing. Next visit we will see it and its companion temple, the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests -- where the emperor prayed each August for a bumper harvest. Saved also for a subsequent visit is the Great Wall, for the next day we took the plane back to Kunming, where "settling in" continues.

* * *

Special report on SARS.

We stayed a couple of nights in Hong Kong, just as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome was hitting there, on our way out of China in mid-March for three weeks’ vacation in the US (California, Arizona). On the Ides of March in Hong Kong, there was really no indication of SARS; the crisis was unknown to us, indeed, to almost everyone. About the town, not a poster, slogan, nor picture exhorted anyone to beware. Susan even went to a couple of hospitals, including the very hospital from which the first case in the city was later reported, for routine tests and a physical exam. No one was wearing masks.

On the Cathay-Pacific flight back to Hong Kong from San Francisco, cabin crew and some passengers were wearing masks, and then when we got to the Hong Kong airport, where we spent five hours waiting to connect to our return flight to Kunming, about 2/3 of the people at the airport were wearing masks. In fact, the Hong Kong government only recommends masks for people who have a cold or allergy and would be sneezing on others. This whole environment created an amusing situation where not a single person on plane or in airport dared sneeze. If some did sneeze, it would be like tipping a tray full of marbles, with all the marbles, but one, moving to the other side, as far away from the offending marble as possible. We did not hear a single sneeze from San Francisco to Kunming.

Hong Kong is now taking this seriously, though. Elementary and high schools are closed until the 21st, and universities are closed until the 13th. Another amusing thing about this serious ailment has to do with the HK-mainland relationship. Whenever anything goes wrong in Hong Kong, the Hong Kongers blame it on neighboring Guangdong province, specifically Shenzhen, the mainland Special Economic Zone Deng Xiaoping created in 1980 which tries to mirror Hong Kong in all things. Usually they are right.

* * *

Historical postscript: The Hong Kongers were indeed right. A year or so later we learned that SARS originated in Shunde, Foshan, Guangdong. The first patient, a farmer, died a short time later, with no real understanding by doctors of the pandemic that was brewing. Government officials did take some precautionary steps but did not inform the World Health Organization of an outbreak until the following February.

The course of the disease was dramatic. On February 21, Liu Jianlun, a 64-year-old a Chinese doctor who had treated cases of SARS in Guangdong arrived in Hong Kong to attend a wedding. Although he had developed symptoms about a week earlier, he initially felt well enough in Hong Kong to shop and sight-see with his brother-in-law. But the day after his arrival he sought emergency care at the Kwong Wah Hospital in Kowloon and was admitted to the intensive care unit. He died on March 4. About 80% of the Hong Kong cases have been traced back to this doctor. The day after Liu was admitted to hospital, a 47-year-old Chinese-American businessman, Johnny Chen of Shanghai, who had rented the room on the 9th floor across the hall from Dr. Liu in Hong Kong, travelled to Hanoi; he was admitted to The French Hospital of Hanoi on February 26. Seven days later, on ventilator support, he was medically evacuated to Hong Kong. Seven hospital workers who had cared for him had already developed symptoms of SARS. Chen died on March 13. At least 38 health-care workers in Hanoi ultimately became infected with SARS. On February 25, the 53-year-old brother-in-law of Dr. Liu came to the Kwong Wah Hospital. He was not admitted that day, but he worsened and was admitted on March 1. He died on March 19. On March 4, a 27-year-old Hong Kong man who had visited a guest on the 9th floor of Dr. Liu's hotel 11 days earlier was hospitalized. About a hundred hospital workers (including 17 medical students) were infected while treating him. This was apparently due to failure to take recommended precautions against the spread of respiratory diseases.

By now the disease had spread through air travel, with cases occurring not only in Hanoi, but Singapore, Taiwan, Vancouver, Toronto, Bangalore and Beijing -- 37 countries in all. Tourism to Hong Kong virtually ceased, and to Beijing also.

But remarkably by early May, the epidemic was effectively over. The number of newly infected people in Hong Kong dropped to less than ten and by month's end to zero. Like lights coming on at night, the cities most affected were one by one cleared of the World Health Organization's tourism warnings that had been issued in March and April.

The final toll was 8,422 cases, with 916 deaths worldwide. SARS is "fully contained," but has not been "eradicated."

* * *

We in Kunming did not know the final story that April, however. I could only remark then that:

Guangdong and Hong Kong are far away from Kunming, where I don't know of any cases, despite incidences in both Sichuan province and in Vietnam, Yunnan's neighbors. There are rumors, of course. The first case has been rumored on several different occasions, but the western doctors here, whom I would guess have the best information, say none have been reported.

The one effect I felt personally was felt indirectly and was a result of a decision by the Peace Corps. My wife had discovered earlier in the year that Peace Corps workers in China were confined to a single function by the Chinese government: teaching English. China is not a poor third world country, thank you very much, but Peace Corps workers can come and help with the nationwide effort to learn the world's lingua franca. By some convolution, however, Peace Corps workers were allowed to volunteer for an environmental project of some sort in the summers. One Ning, of New Jersey, teaching in Sichuan, had heard about my budding effort to establish a conservation data center in Yunnan and contacted me early in the year with the hope that she could work on that this summer. I was of course delighted at the prospect. But then on April 1, all Peace Corps workers were called back to the states because of SARS. Ning ended up working in Bulgaria for a year.

* * *

In fact, we had a very nice time in Hong Kong on the way out, oblivious as we were of the epidemic swirling around us. Ignorance can be bliss. Alex got to go ice-skating at an indoor rink in a ritzy shopping mall with the daughters of some professors we know in Hong Kong. After Alex and I left for the states, Susan stayed on a couple of days more, then returned to Kunming to take care of our dog, whom our friend Ming had cared for while we were all absent from Kunming.

Alex and I flew to SFO, made our way down to the Monterey area and picked up my car. After staying a couple of nights with friends in Watsonville, we drove to Scottsdale in a single day (12 hours). An enormous full moon rose on the desert horizon directly ahead of us as we were driving east in Arizona at night. We had a lovely week with my mom in Scottsdale, a snowbird from the Chicago suburbs. Alex was in the heated outdoor pool at least twice a day.

Now that we are back in Kunming, Alex is back in school, and I regularly pick her up at ten minutes after noon and take her to lunch at our favorite noodle shop, where we each have a large steaming bowl of rice noodles with a few specks of meat in the broth (50 cents). Our friend, Wu, one of the ecology grad students, often joins us. Last Friday I was explaining the Delphic Oracle to Wu. Alex piped up "You mean I could ask her questions like, 'Will I live to be a hundred?' and "Will I remain forever young?'"

* * * ~ * * *

Here is the difference between living in China for a few months and living here for a year and a half:

In the walk around Green Lake, described a few months after we had settled in, I mentioned passing "a man rotating stainless steel billiard balls in one hand." It was a mystery why he was doing that -- maybe it was for arthritis. But why then a second man doing the same thing, but walking backwards?

I now know that there are two balls, that they can be made of whatever cue balls are made of as well as stainless steel (I once saw a guy with two walnuts), and that they are not for arthritis. They are exercise for the mind. The Chinese believe that the hand and the mind are connected in a special way and that exercising the skills of the hand keeps the mind sharp. Why are the hand and the mind thought to be connected in a special way?

That is what it is like to live in China for a year and a half: one mystery solved, another opens up.

Here is another one: Chinese children do not line up alphabetically by last name –- having no alphabet. What do they do?

* * *

In January a year ago, a few months after we'd settled into our apartment, Susan, Alex and I and some friends of ours were walking through the pagoda and carp pool section in the middle of the island in the middle of Green Lake. It was a mild, sunny winter day. Susan paused in conversation, and I went ahead a bit. A man asked me, "Are you an American?"

I said, yes, I was. Oh, he had always loved America, such a beautiful country. He had had friends who were Americans. He had worked with the Flying Tigers when he was a young man.

That was 63 years ago. I suppose "young man" could mean 16 or 17, which would make him 79 or 80. He looked to be in remarkably good shape for 79 or 80. I went and got Susan, who is very interested in the Flying Tigers and had been helping a man who is the local expert on them. She was delighted to meet our new friend, and he her. We introduced him to Alex and our friends. We wanted to stay in touch with him. He said he was living in a home some ways away and he did not get to the park often, but he gave us his telephone number.

We called him repeatedly over the next month but could never get an answer. The phone would ring and ring. We were forced to give up trying to contact him.

Almost a year later, I was walking through the island on my way home. I was passing that place where you can rent little boats made to look like submarines, which you take out with your child so she or he can shoot the little laser gun at “mines” floating in the water and set off a very satisfying blast of water squirting straight up into the sky. A sign on the ticket booth explains the terms of rental both in Chinese and in English. A Chinese man was standing there reading the English out loud.

I walked past him at first, but then came back to look over his shoulder while he finished the last sentence or two. I told him that was very good. We started talking, and I realized he was the same man we had met almost a year ago. He did not look to be a day older. His name is Zhou Jintao. His English name is Peter. He had recently moved to an old people's home nearer the lake. I told him I did not want to lose contact with him again, so I took down both his new telephone number and the address of the place where he lives.

A week later, I made arrangements with him to take him to dinner. Two grad students, Bin and Wu, and I found the place where he lived, down an alley off of a main street, got the gatekeeper to roll up the metal garage door which comes down to cover the entrance, and found him in his small room listening to VOA. On the way to dinner, I asked him if he had ever married, a natural question since he was living alone with apparently no family to take care of him. He said, "No, I was considered a political undesirable and no woman would marry me."

We had dinner at a Thai restaurant and talked about the Flying Tigers. He had had a friend named Bill from the state of Washington, from a town called Shadow. Jintao worked in a bank, and he and Bill had dined together frequently. Jintao credits American strafing as an important factor in the Battle of Tengchong, when Chinese troops drove the Japanese out of SW Yunnan. Tengchong, an area of hot springs and dormant volcanoes, about ten hours by bus to the west of Kunming and not far from the Burmese border, is the furthest Japanese troops managed to advance into the western half of China. If they had won at Tengchong, the whole supply line for Chiang Kai-shek’s armies -- from India, over the Hump, to Kunming -- might have been severed.

On the way back I asked him "What made you politically undesirable so that no woman would marry you?" He said, "In 1958 I was labelled a 'rightist' and imprisoned for 21 years."

That took me aback! Not every day do you meet a man like that. But I recovered sufficiently to ask, "How did you get out? -- Did Deng Xiaoping let you out?"

"In 1979, Hu Yaobang, Deng's protégé, raised the issue of political prisoners in Yunnan with Deng. Deng nodded his head, and we were let out." (Hu Yaobang two years later became Party Chairman, then General Secretary of the Communist Party, in which positions he pursued economic and political reform. This was opposed by other members of the Old Guard, and when student demonstrations broke out across China in 1987, Deng was forced to remove Hu from his posts, though he retained his seat on the Politburo. His death in April of 1989 sparked the events of Tiananmen Square of that summer.)

Peter Hessler, gifted observer of people's lives, tells a similar story in River Town: Two Years on the Yangtze. Hessler, a Princeton and Oxford grad, who came to Fuling, a city in Sichuan Province, as a Peace Corps worker and who at the time I write is The New Yorker's China correspondent, met Father Li, whose great-grandfather was converted to Catholicism by French missionaries in the early part of the 19th century.

The Li family lived in Dazu, not far from Chongqing, and Li Hairou was the second son of a shopkeeper. At eleven he was sent to a French-run parochial school in Chongqing, and then in Chengdu he studied to be a priest. He learned French and Latin, and, like the other young seminary students, he dreamed of studying in Rome. Others were sent to Italy, but Li Hairou stayed, becoming a priest in 1944, at the age of twenty-nine. Three years later, he was sent to Fuling -- remote, undeveloped, a distant backwater of a poor province. Perhaps in another age it would have been a quiet post. But the midcentury was a time when nothing in China was quiet, when the War of Resistance Against the Japanese was followed by the Civil War and Communist Liberation, and these were struggles that touched almost everybody in the Chongqing region. Li Hairou's older brother died during the wars, and his younger brother, having found himself on the wrong side of Liberation, fled to Singapore, where he married and became a teacher.

Father Li, however, stayed in Fuling, where (amazingly) there were three thousand parishioners. There were also two French priests who lived in the area, "waiting for the ripples of revolution to make their way down the Yangtze Valley. And then the French were gone, and the ripples came to shore, and Father Li had to wait no more."

Father Li's Catholicism was in trouble first because it was Foreign Teaching, a doctrine which I imagine was not applied to nuclear physics. He was sent to work on the docks, sweeping and cleaning. Then later it was in trouble again because the Cultural Revolution set out to Destroy Superstition. At one point he was watched night and day by four Red Guards, and five times a week he was marched through streets with a sign saying 'Down with Imperialism's Faithful Running Dogs'.

He was also given nothing to eat but a bowl of rice in the morning and another in the evening. Six priests in Chongqing died under this regimen.

There are plenty of other stories here, most of them in a far lighter vein. For example, there is one told me by John Israel, professor of Chinese studies at the University of Virginia, who was the first American scholar to come to and study this area after Nixon recognized Red China. The story is about Doug Briggs, M.D. Briggs is a young doctor trained in the West who offers his services free of charge to all comers (including me and my family) as part of a charitable program called Project Grace. He has been here for some years and has children and you can't invite him anywhere because he is too busy.

Dr. Briggs likes to have his shoes shined because it gives him an opportunity to talk to the shoeshine people. He gives them two kuai (25 cents), instead of the usual one, "because there are two shoes, not one."

One day he was having his shoes shined by a young woman. He asked her where she was from. She said she was from a nearby mountain village. He asked her how things were there. She said, "Not so good, my mother is dying of tuberculosis."

"But tuberculosis is a treatable disease; she shouldn't have to die."

"But she also has liver cancer."

"Well, that's another matter. How far away is your village?"

He figured out that he could get up there and come back all in the same day, so he decided to go. They hired a car and drove as far up the mountain as the road would take them. Then they walked for three hours. When they arrived, they saw a body covered with a tarpaulin in front of the woman's house. Doug said, "It appears we are too late."

The young woman went up to the tarpaulin and pulled it back. There was her mother. Her mother said to her, "So you've come!" She had been lying there for three days and nights. It is the custom in the village to take a person in the throes of death out of the house and let them die under the blue sky.

Doug examined the young woman's mother. From what he could tell, her liver seemed not abnormal. Her pulse was steady. Her heart sound as if it was muffled by fibrous matter, as happens with tuberculosis.

He encouraged her to sit up. She said she couldn't. He encouraged her again, and she sat up. After a while, he encouraged her to stand. She said she couldn't. He encouraged her again, and she wobbled to her feet. He gave her a staff to hold on to, and she made it back into her house.

The villagers were illiterate. He had two bottles of pills, one yellow and one brown. He said, "The yellow ones are for the morning, when the sun has risen; the brown ones are for the evening, when the sun disappears from the sky."

The villagers laid on a feast for him and the daughter. When the feast was over, they brought out a goat. "I'm afraid I only treat people, I know nothing about treating animals." "We don't want you to treat this animal, we want to give it to you." A few minutes later he had a bag of goat meat.

The slope up to the village was so steep that the walk up, which had taken three hours, took but 45 minutes on the way down.

* * *

About a year and a half after we first set foot in Kunming, The New York Times business section featured an article entitled "Is China's Economy Turning into the Next Bubble?" by Keith Bradsher.

Japan had its bubble in the late 1980's, when the Imperial Palace grounds in Tokyo became worth more than all the land in California. [Astounding, but true! -- I have read this elsewhere also]. Thailand and Indonesia had their bubbles in the mid-1990's, when speculators and multinationals poured money into what seemed like a Southeast Asia miracle. The United States had its Internet and telecommunications bubble in the late 1990's when stock prices looked as if they could rise indefinitely and unemployment kept hitting new lows.

Each bubble burst, "with millions of families losing their savings and many losing their jobs." The article is accompanied by four graphs showing these bubbles in terms of excessive investment, in offices, factories and equipment for Asia and in equipment and software for the US. The graphs take average annual capital expenditures 1980-2003 and then for each year plot the percentage by which these expenditures exceeded or fell below the average. Each one shows a sharp rise in the bubble years to an excess of over 20% and then a steep fall into negative territory when the bubble burst. Each one except China, where expenditures are now at the above-20% level.

The article focusses on Dongguan in the Pearl River delta region of southern China, twenty-five years ago "an impoverished farming village" where today there are 14,000 foreign-controlled factories and floor space can be rented for 10 cents a square foot per month (excluding installation of pipes and wiring), compared with $1 to $1.50 a square foot in parts of America and as much as $2.50 in Germany. Base wages at the focus company run by a German businessman are $60 a month, with an additional $40 in overtime, plus free room and board; the system pioneered in Southeast Asia of employing young women from rural areas is used, the women returning home after one to three years "to start small businesses or families".

"Business executives and economists often complain that factories are built with little attention to whether similar plants are being constructed elsewhere, or to how low prices will fall if all of them start churning out the same products at the same time." The cycle is fueled in part by former farmers who have taken the profits from their land sales and built more factories rather than putting the money in banks paying negligible interest rates or in the "fraud-riddled" stock exchanges. Investment-related spending accounts for nearly half of China's economic growth, "an extraordinary figure that reflects public spending on highways and dams, as well as private-sector projects." Further, China's "special disadvantage" is its buy of commodities. (These include oil, China being now second only to the US as a buyer of oil). All those factories find that materials are their biggest cost "by far," and any rise in this cost can erase competitive advantages -- yet the increase in demand China's own purchases create is driving prices up.

There is also a banking crisis. 45% of the loans of some banks are nonperforming, but loans keep coming due to the fact that in order to maintain the fixed exchange rate with the dollar, the central bank immediately exchanges all the dollars which exporters, foreign investors and speculators deposit for yuan in order to keep dollar-holders from bidding up the yuan's value. The banks then lend these expanding deposits, with loans rising 21.4 percent last year. The article quotes the chief Asian equity strategist at Smith Barney, Ajay Kapur: "The world economy is being kept afloat by the aggressive expansion of the U.S. budget deficit and Chinese loan growth."

* * *

Another book worth reading is Paul Theroux's old book, Riding the Iron Rooster, about his year-long train journey (my idea of hell) across Asia and through China. It is not an old book so much in terms of years (published late 80's), but rather in terms of the immense changes which have taken place here since he wrote it.

Even the following has changed, though there is still some truth in it:

Everything they did was connected with food -- planting it, growing it, harvesting it. The woman who looks as though she is sitting is actually weeding; those children are not playing, they are watering plants; and the man up to his shoulders in the creek is not swimming but immersed with his fishnet. The land here has one purpose: to provide food. The Chinese are never out of sight of their food, which is why as a people arrested at the oral stage of development (according to the scholar of psycho-history Sun Longji) they take such pleasure in fields of vegetables. I found the predictable symmetry of gardens very tiring to the eye, and I craved something wilder. So far [he had not been in China long], China seemed a place without wilderness. The whole country had been made over and deranged by peasant farmers. There was something unnatural and neurotic in that obsession. They had found a way to devour the whole country.

One of the most amusing things about Theroux's book is the display of his prejudices, most of which have nothing to do with China in particular. At one point, for example, he is told of a school for animal training. "This interested me greatly, since I have a loathing for everything associated with performing animals. I have never see a lion tamer who did not deserve to be mauled; and when I see a little mutt, wearing a skirt and a frilly bonnet, and skittering through a hoop, I am thrilled by a desire for its tormentor (in the glittering pants suit) to contract rabies."

Theroux came to Kunming. More about that later.

* * *

Let's go back now to the men rotating stainless steel billiard balls in one hand: back to the Chinese belief in the connection between the mind and the hand.

I read recently of a study at Regensburg University in Germany, reported in the journal Nature, where subjects spent three months learning to juggle. They then quit juggling completely for a further three months. Areas of their cerebral cortex, the thin layer of nerve cells on the brain's surface where higher thought processes (it is thought) occur, were measured three times: before the learning began, after the skill was learned, and then again after the three months of retirement from juggling. The cerebral cortex enlarged after the learning and then began to shrink during the retirement. It seems the Chinese already knew this, or something very like it.

Chapters are sometimes supplemented by notes. Click Random Footnotes to see.

Table of Contents

Home page

Welcome to a journey, riding webbook or ebook. We alternate between roughly chronological "feet on soil" chapters and "nose in books" chapters. The introductory web posting

of the first two chapters is in full. Click Additional for other postings. The complete ebook, sans ads of course, is available now for purchase:

Click here