Green Lake: Reflections from the Surface of China

4/ Three Explorers

Anderson

![]() wo men stand on the tarmac of the aerodrome at Kunming waiting for a third, arriving from Chengtu. One is Long Yun, Governor and warlord of Yunnan province. The other, contemplating his companion, sees Long as someone "who is, and looks, a heavy-opium smoker." Long is a Lolo, a people from the Northeast of the province, short-of-stature but big enough as warlord to prevent the third man from taking over his province. The third man, the one flying to Kunming, is Chiang Kai-Shek. It is April 1936.

wo men stand on the tarmac of the aerodrome at Kunming waiting for a third, arriving from Chengtu. One is Long Yun, Governor and warlord of Yunnan province. The other, contemplating his companion, sees Long as someone "who is, and looks, a heavy-opium smoker." Long is a Lolo, a people from the Northeast of the province, short-of-stature but big enough as warlord to prevent the third man from taking over his province. The third man, the one flying to Kunming, is Chiang Kai-Shek. It is April 1936.

This second man is an Anglo-Irishman, James (Shaemas) O'Gorman Anderson of the Chinese Maritime Customs. When his eyes turn from Long to his own situation, they see not the spotless sky and bright sun in which he and Long are standing, nor even the umbrellas held by underlings to shade them from it. He sees clouds.

"This Carry on! posture has become ridiculous! The CMC's glory days are long gone. Our foreigner-run bureaucracy used to labor for the holder of the Mandate of Heaven, not only collecting customs duties on the very active trade between the West and China, but running the postal service, managing harbours and waterways, weather reporting, catching smugglers (my specialty), overseeing loan negotiations, currency reform, and financial and economic management. Among other things! Like diplomatic affairs, for example. I remember that when I started it was so simple. We supervised collection of the money and gave it to the emperor or empress. Our bosses walked over to the throne room when they wanted to get things done. We provided 1/3 of China's national revenues, for God's sake. But the Ch'ing fell: all hell broke loose. Warlords everywhere! It was said then that the writ of Peking no longer ran much beyond the city walls. Indeed, on some occasions not even to the city walls, as when the mandarins found themselves short trying to pay the local police and had to get us to find silver shekels and deliver bags of them to the police stations. Now we have to take actual delivery of customs taxes ourselves, rather than using Chinese intermediaries. Then we deliver these taxes in turn to an international banking consortium in Shanghai in order to vouchsafe China's credit rating. Then Sun Yat-sen demands that, for his area around Canton, he take over control of revenues. Instead, the treaty powers send fifteen naval vessels to put an end to that idea! In comes Maze, my boss. Carry on! 1929, and Chiang consolidates control. For a while a semblance of the old imperial system. True, no more foreigners hired at CMC, but those already there can stay until we retire. Increasingly few are we. Then the Japanese, like a plague of locusts. Occupy Manchuria and trouble our ports. Demand our silver. Incredible things happen. Like that time Stella and I were in Nanning and warlords were bombing each other -- bombs falling everywhere! -- and one warlord calls up and wants to play tennis and have tea! Now who do we deal with? Take Long Yun here. He's got all the opium and tobacco in the world, plus a private army of 100,000. His own silver currency, for Christ's sake. He's just humoring Chiang, waiting to greet him. And what am I doing here? Carry on!"

Perhaps that wasn't precisely Shaemus's interior dialogue, but possibly it is not far off the mark. At any rate, his career (and his plight) are compellingly retold by his son Perry, conceived (as he says) in China, educated in England, a professor at UCLA: "An Anglo-Irishman in China," published in The London Review of Books and then collected in Perry Anderson, Spectrum (2005). There are some Yunnan connections, indeed Perry’s brother, Benedict, was born in Kunming. The following short summary tries to do the account justice, but the original is peerless, and readers are hereby encouraged to seek it out.

Why had Shaemus come to China, journeying there during the very days when the First World War was breaking out, just age 21? Perry explains:

After a year as a classical exhibitioner in Cambridge, neglecting or scorning his curriculum, he had failed his first-years exams. Outraged by this nonchalance, his father, a martinet, refused to let him sit them again, cutting off financial support. His uncle, another and more senior general, who had once commanded the garrison in Hong Kong, no doubt recommended him for service in the Maritime Customs. Academic grief was actuarial good luck. Gazetted into his future employment just before the outbreak of war, and issued with an 'outfit allowance' of £100, he was contractually bound to five years’ service in China. Unable to secure his release to participate in the slaughter in Europe, he escaped the fate of his younger brother, the apple of his parents' eye, killed in the last months of fighting. This death finished off his father. He had punished the wrong son.

CMC had its origins in the multiple political and social earthquakes the Ch'ing dynasty was subjected to in the mid-19th Century: Opium Wars, Taiping Rebellion, the "opening up" to the outside world and the imposition of a "Treaty system" and the foreign-manned customs service. Foreign-manned but largely loyal to the Ch'ing rather than to the home country. Thus British and French could work side by side with German in the CMC even as their compatriots were slaughtering each other at Verdun, at least until the final stages of the war. Robert Hart, the Ulsterman who was the first Inspector General of CMC had been pressured into becoming British ambassador to China but had refused. Why give up power?

Despite that Robert Hart had died three years earlier, as had China's last dynasty, Shaemus's career at CMC started out on a traditional trajectory. To wet his feet, he is first assigned to northern Hunan province in the center of China. In one of his letters home he notes that 15,000 troops under the command of the then most powerful warlord in the country were also assigned there and that if you went out at night there was a chance a soldier might mistake you for an infiltrator and shoot you dead. Nine months later he is in far northern Mukden, starting one year of intensive training in Chinese, training which continues in one form or another for a further nine years. When the year is up he is sent to Ningpo, a port city along China's central coast. From there to Peking and CMC headquarters. Soon after arriving, a warlord with visions of restoring the fallen Ch'ing dynasty seizes the city and has to be attacked and expelled by rival warlords. "There are bullet holes in our office windows." Somehow the CMC gains from all this conflict, controlling even larger sums, negotiating with the diplomatic corps, and "taking over the government banks practically." In 1920, Shaemus transfers to Chungking, years later China's capital in the war with Japan and still later (as Chongqing) site of the downfall of Bo Xilai and his Maoist revivalism. (Continual transferring of personnel was CMC's way of preventing local attachments interfering with orders from HQ). In 1920, the city is contested by forces from the home province and those from Yunnan. Civil war, and trade is at a standstill. Shaemus is visited by three lady friends from Peking, one of whom, the wife of an Embassy official, he is having an affair with. One of the ladies she brings along with her, Stella Benson, falls in love with Shaemus. More than one conflict taking place in Chungking.

1921 and he sails for home on leave and ends up marrying Stella. They motor across America on honeymoon, then return to Ireland in the middle of a civil war. Chungking at home. Off to China the "day after Collins met retribution in Cork," as son Perry puts it. Sent to Yunnan, to Mengtze, just above the border with Vietnam.

Yunnan, famous for its natural beauty and hospitable climate, was a province of China whose remoteness and ethnic diversity made its warlords virtually independent rulers. . . . There for two years, the young couple lived in a long adobe house 'on high stone foundations with a curling Chinese roof gaily painted underneath in faded blues and oranges and crimsons' . . . Stella fell violently out of love, my father into hurt brooding."

Shaemus is called to Shanghai, while Stella heads back to England. Sun Yat-sen is cohering his power base in southern China, calling in Soviet advisers.

At this juncture, just as my father left Shanghai, British sepoys in the city fired point-blank into a Chinese crowd demonstrating for the release of students held in a British police station. The massacre of 30 May 1925 set the country alight. A general strike was declared in Shanghai; anti-British rioting erupted and spread to other cities. Three weeks later, a major demonstration against the unequal treaties in Canton met with an Anglo-French fusillade that left many more casualties.

Shaemus is then reassigned to the part of China closest to Vladivostok and on the border with Korea, an area where Japanese expansionism is being exercised through the local warlord, the "Old Marshall." Cross-border trade is active; Stella rejoins him, writing a novel about the experience of being there. Despite the cold, things get hot. Chiang Kai-shek launches his Northern Expedition in 1926 to suppress warlords not yet in his control; various surtaxes are imposed by various imposers; disputes arise over who collects what and where the dough goes. The Japanese warn Shaemus that "Korean thugs" (their name, presumably, for any Korean seeking independence from Japan) are out to kill him, though he is in fact fine with Korean independence. "Machine guns titupped about the streets" Stella writes in her diary. An uncertain calm follows, but leave in Europe is welcomed by our heroes. While they are gone, Chiang completes his Expedition, massacres his former Communist allies in Shanghai, and proclaims a unified national government headquartered in his home city, Nanking. The Japanese blow the Old Marshall up as his train heads back to Mukden.

Carry on! Riding on the Trans-Siberian Railroad back to China, Shaemus worries on the fact that the head of the CMC has changed, that HQ is now Shanghai, and that a doctor has just told him he can never father children. He is assigned to Kwangsi province-- right in the middle of it all!

. . . a backward region along the Indochinese border with a large minority of Thai origin. Its leading generals, Li Tsung-jen [Li Zongren] and Pai Chung-his [Bai Zhongxi], had been more prominent in the actual fighting on the Northern Expedition than Chiang himself, ending it in control of a vast area that for a time included Hankow and Peking. . . . In early 1929, however, Chiang suddenly gained the upper hand over the "Kwangsi Clique', expelling them from the KMT and driving them into exile in Hong Kong.

Yet Nanning, Kwangsi's capital, refreshes both Shaemus and his love of China. He has a house on a river bank looking across to clumps of bamboo and water buffaloes, Chinese washing clothes, junks sailing along; his garden has hibiscus, frangipani, camellia, bougainvillea, tamarisk and various fragrant flowers. Crosswinds continue to blow, however. Twenty-five-year-old Teng Hsiao-p'ing (later Deng Xiaoping) infiltrates troops into Kwangsi via Vietnam and manages to set up a soviet, and all that entails, on the border with Yunnan. The group of left-wing KMT officers Chiang had mistakenly used to replace the Kwangsi Clique prematurely launches a rebellion. The Kwangsi Clique is called back from exile to deal with them, and with Teng. It is at this point that the warlord request for tennis and tea occurs. The only way out of this is transfer -- and this time it is to Hong Kong. "With a morphine-addicted Swedish subordinate in extremis on board, my father and Stella set off in a motor launch, escorted by a gunboat dispatched by the Kwangsi generals." The five-day journey is like a dream, a dream with waterfalls and gibbons. They stop the night at a hamlet. Stella, incredibly, is brought a telegram from her London publishers.

Carry on! In Hong Kong, after Stella leaves, Shaemus falls into another turmoil, this one between the Brits who control the colony and his CMC masters who are insistent to maintain that although they are British they work for China, not for Britain. Smuggling provides some relief, not the dirty deed itself but the suppression of same by vigorously commanding small gunboats patrolling round the island. In 1931, the Japanese invade Manchuria. They make a stab at Shanghai, too, but have less success there. Shaemus is sent to Hainan, "China's Hawaii," though it is just off the southern coast of the mainland rather than in the middle of the Pacific. He is sent there because of the smuggling problem and because of his recent expertise in dealing with that. Stella makes her way back to China but falls ill.

In the autumn they went to Tonkin, where he had Customs business. She stayed on after he went back for a few days in the Baie d'Along, famous for the allure of its mountainous islets. There she caught a last pneumonia, and died. My father buried her on an island in the bay.

The Long March begins. Back in London, Shaemus meets a woman twelve-years his junior. He eventually proposes; they wed that fall. (This is the mother of Perry Anderson and his brother Benedict; so much for the doctor who told Shaemus he was infertile.) The couple arrives in Kunming in February 1936, a time when a portion of those making the Long March are marching through Yunnan, a situation serious enough that Chiang Kai-shek travels down to Kunming to meet with Long Yun. This is why Shaemus is standing on the tarmac at the aerodrome that day in April brooding over the CMC.

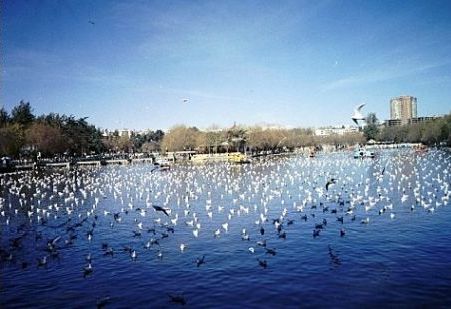

His work isn't going well, either. He is continually frustrated by local Yunnan authorities in his attempts to collect customs revenues and put down smugglers. He believes Chiang has brought China under centralized command, but it is beginning to dawn how false that is. Still he likes Kunming, "one of the most charming places in China."

Set on a high plateau, under massive russet walls, pierced by four ornamental gates, and surrounded by hills covered with camellia and fruit-blossom. The Liang river flowing past my father's office ran down to Lake Dian just south of the city, from whose western shore rose the steep-escarpment of the Hsi Shan: temples and shrines on the mountain-side, sampans and islands in the water below. . . . fetes champệtres in the hills, midnight swimming in the lake . . . children's parties in the garden, wives of the Governor or his cousin for tea.

But the war with Japan begins. Chiang again demonstrates his military incompetence, throwing his divisions against the Japanese at Shanghai "in a botched assault that was eventually cut to pieces with a quarter of a million Chinese casualties, and headlong retreat to Nanking." Somewhat later, the intellectuals at the two leading universities in Peking and those at Tientsin, fleeing the war zone, set up shop at the new "associated university" in Kunming. Long Yun, remarkably, does not clamp down their free discussion, unlike Chiang who demands that all toe the party line.

Before the university forms, Shaemus is off to the treaty port city of Swatow (now Shantou), where his anti-smuggling efforts assume military proportions. Japanese destroyers lie just off the harbor in preparation for an eventual takeover. From Swatow to Wuchow. The Japanese seize more and more territory -- they demand that CMC revenues henceforth be deposited in a bank in Yokohama and that CMC hire Japanese. Since the former would create strains with Britain and the US, CMC's Inspector General is able to substitute a Hong Kong bank for the one in Yokohama and to go slow on the hiring. But then the Japanese capture Canton and are then in control of 90% of revenue. CMC must meet expenses by asking for Japanese reimbursement. "Still legally a servant of the Chinese government in Chungking, the Inspectorate-General was now dependent on the remittances of a government at war with it." Carry on!

Shaemus is eventually sent to Lungchow, on the border with Vietnam. Goods and supplies bound for the Nationalist government are pouring through the little town, taxed at increasing rates by that same government. Japanese bombs are falling. Shaemus has to take cover in caves. Son Perry points out that this all has an effect on his father, hitherto predominantly a company man, but now sharing the experiences of the nation the company serves:

The resourcefulness of ordinary Chinese, their extraordinary ability in time of war 'to get ten litres out of a litre bottle' made a deep impression on him, and he became correspondingly more caustic about the authorities set over them.

The Japanese land troops in Vietnam who march north through the border to capture the provincial capital in early 1941 and cut off this route of support for the Nationalist government. (Hello, Flying Tigers and the Hump). Tiny Lungchow is repeatedly bombed from air and sea, for no apparent reason. Shaemus heads for Shanghai, where the I.G., Maze, gives him a desk job and a place to live in the International Settlement, surrounded though it is by Japanese troops and warships.

In April, twelve months leave came due. Maze, reluctant to let staff go, tempted him with Tientsin, the second largest port in the country. My mother put her foot down. Europe was out of reach. We sailed in the President Coolidge for San Francisco.

* * *

Fairbank

![]() he Anglo-Irish Shaemus Anderson came to China from England in 1914, a failed scholar lucky to have gotten a job even if it was on the other side of the world. The American John King Fairbank came to China from England in 1932, Harvard summa cum laude and then a Rhodes scholar at Oxford. Anderson’s story is told by his son, Perry; Fairbank wrote his memoirs, Chinabound. One connection between the two men, who never met, was that Anderson worked for Chinese Maritime Customs and Fairbank anchored his long academic career writing about it. Anderson died at age 53; Fairbank lived to be 84.

he Anglo-Irish Shaemus Anderson came to China from England in 1914, a failed scholar lucky to have gotten a job even if it was on the other side of the world. The American John King Fairbank came to China from England in 1932, Harvard summa cum laude and then a Rhodes scholar at Oxford. Anderson’s story is told by his son, Perry; Fairbank wrote his memoirs, Chinabound. One connection between the two men, who never met, was that Anderson worked for Chinese Maritime Customs and Fairbank anchored his long academic career writing about it. Anderson died at age 53; Fairbank lived to be 84.

Fairbank remembers his first sighting of China’s capital:

Approaching Peking by rail across the brown winter plain in 1932 still had the emotional impact it had during the five hundred years since the city walls were built. For Peking until the 1960s was the world’s most populous walled city. Granted Nanking had a bigger wall, but it lacked the setting on a plain. the crenellations, on top of the forty-foot façade, the regular row of bastions jutting out two bow shots apart, the sheer visual length of the walls, four miles on a side punctuated by corner towers and nine tall gates in the Northern (‘Tartar’) City, five miles by two-and-a-half with seven gates in the Southern (‘Chinese’) City – all this display of square, man-made strength rose clean from the plain, as yet hardly cluttered by suburbs. There was no other site like it in the world.

Fairbank, like the other two men profiled in this chapter, had no connection to China before he decided to go. He was not the son of missionaries, not brought up in the Middle Kingdom. His grandfather, he tells us, was a Congregational Minister, one who moved on from one small town in the Midwest to another when his sermons grew stale. But his father “quietly broke free of organized religion. After reading the Bible through every year, my father concluded that he had got the Christian message and had received enough spiritual guidance to last for his lifetime.” His father graduated from Illinois College in Jacksonville, Illinois and became a lawyer in South Dakota. His mother, who had “the greatest influence” on the future professor, was the daughter of Quakers originally from Virginia and was delayed in her education by the depression of 1893. But she entered the University of Chicago in 1899, age twenty-five, where she specialized in literature and speech. She lived to be 105.

The idea of making the study of China his profession had been suggested to him by a British professor at Harvard as relatively virgin academic soil. Professor Fairbank took this and ran with it, eventually becoming without doubt the foremost expert on China in the United States of his time, an honor which entailed a certain glory but one which also provided him a certain amount of tsuris during the McCarthy Loss-of-China Period.

He stayed in Peking until 1936, marrying there Wilma Cannon, who was the daughter of a famous Harvard physiologist; Wilma became a historian of Chinese art. The couple returned to Cambridge, MA so that he could take up a teaching position in the new field of Area Studies at Harvard. He was called to Washington, DC the summer before Pearl Harbor because the US was in the earliest stages of setting up its spy agency, the Office of Strategic Services, and it needed experts to feed it information about China and Japan (which had been at war since 1937). Actually, the OSS was not formally created until a year later, but the office of the Coordinator of Information, for which Fairbank came to town, was headed by the same man, William Donovan, who became head of OSS. After about a year in DC, Fairbank went back to China, landing in Kunming in September 1942.

Here are the stops (many of which are overnights) on his flight there, which originated in Miami on August 21: Puerto Rico - Trinidad - Belem - Recife - Ascension Island - Accra - Lagos - Kano [overnight at Maiduguri] - Khartoum - Cairo - Basra - Karachi - New Delhi - train to Allahabad military base - Assam - (over the Hump to) Kunming, arriving September 20. Most of this was on the late and lamented airline, Pan Am, which flew twin-engined prop planes, DC-3s: no cabin pressure, no AC, no heat. Welcome aboard!

He only stayed in Kunming for about five days, though long enough for him to be depressed and angry about how both the Chinese and US governments were failing to provide resources to the wartime university, Lianda, set up there from fleeing faculties driven out when Japanese troops took over Peking and Tientsin.

On September 25 he flew on to Chungking, the wartime capital, where he stayed until December of 1943 and where he joined a number of the other masters whose books I try to honor here. Fairbank’s stay in Chungking is notable for his observations about the people there, but he was, despite working for the OSS, not a spy -- really an information gatherer, one who succeeded in getting information flowing both ways, including to those professors in Kunming who wanted to keep current academically.

Fairbank’s memoir, Chinabound, is certainly a masterpiece of sorts, and he wrote a number of other books in the masterpiece class. But I focus on him here because just one of these was my first introduction to the history of China in the 19th and 20th century. I still remember finding it in a bookstore in Hong Kong and the great enjoyment I had in finding out a lot about the place to which I returned regularly. For more on Fairbank himself, there is an interesting short account in Jonathan Spence’s Chinese Roundabout (1992), which also includes a brief review of the following book.

* * *

The December 1st Movement, the commemoration of the 60th Anniversary of which I attended, is featured in The Great Chinese Revolution 1800-1985 by John King Fairbank (1987), a book which still today makes a wonderful and absorbing introduction to modern Chinese history. Any country lucky enough to have a survey this good done of its history over this period is a lucky country indeed.

Aside from virtues like insight, comprehensiveness, useful concepts, clarity, and a vastly interesting story, the book is deliciously funny. Items:

~ River dikes "were mended by engineers so competent that they could use comparatively vast imperial allocations of funds to build dikes that would look good enough but last only a few years.”

~ "The Son of Heaven, even when stupid, like that late Ming emperor who spent his time in carpentry."

~ Missionaries and warlords were not always at loggerheads: one American missionary wife "found the bullets of a warlord besieging the city were hitting the mission residence. She wrote both generals, inside and outside the walls, and they stopped shooting to let the American family squeeze through the city’s north gate for a vacation in the hills."

~ "In the days of John Foster Dulles’ Presbyterian crusade against ‘monolithic atheistic communism' "

~ Mao as a swimmer: "Photos showing his head on top of the water suggested Mao did not use a crawl, sidestroke, backstroke, or breaststroke, but swam instead in his own fashion, standing upright in (not on) the water."

~ The Cultural Revolution: "For intellectuals to clean latrines was not simply a matter of a mop and detergent in a tiled lavatory, even a smelly public one. On the contrary, the cities of a rapidly developing China have both modern and early modern plumbing, but their outskirts as well as the vast countryside have retained the old gravity system. The custom, so admired by ecologists, was to collect the daily accumulation, almost as regular as the action of the tides, for mixture with other organic matter and to develop it through composting to fertilize the fields."

The book is also full of fascinating facts, far too numerous to recount in detail. But some of the riper pears can be plucked from the tree for tasting. For example, there is the juicy figure of Sun Yat-sen, often named the founder of modern China. Sun early on had ideas about how China's government should be reformed, and in 1894 he took one of his long, "rather run-of-the-mill" proposals to Li Hung-chang [Li Hongzhang], China’s first great modernizer, sometimes called the “Bismarck of the East.” But Li was too busy even to see Sun. Sun “turned to revolution.” He organized a secret society and created a front organization, the Agricultural Study Society which used a Christian bookstore. He plotted to have Triad Society (Chinese mafia) fighters put their guns in casks labeled “Portland cement” and then ferry themselves across to Canton from Hong Kong, where they would seize government offices and kill the officials. But the authorities were tipped off and put the ferried fighters (who arrived a day late) in jail. Sun escaped to Japan. He went to London in 1896, where he was tailed, kidnapped, and imprisoned in the Chinese legation at 49 Portland Place for twelve days. The embassy wanted to ship him back to China as a lunatic, but he somehow managed to get a message out to his former Hong Kong medical professor, who alerted Scotland Yard, The Times, and the Foreign Office. This combination of police, press, and diplomacy got him released. All this made Sun famous, and he wrote a popular book, now available online, Kidnapped in London, which begins:

When in 1892 I settled in Macao, a small island near the mouth of the Canton river, to practise medicine, I little dreamt that in four years time I should find myself a prisoner in the Chinese Legation in London, and the unwitting cause of a political sensation which culminated in the active interference of the British Government to procure my release.

One of the most important lessons I learned from Fairbank’s book, though, is how our American (and possibly Euro-American) view of China is wrong, 180 degrees wrong.

We in the West tend to think of China as facing east, looking across the Pacific to the Americas and beyond that to the continent of Europe. This impression is reinforced by the fact that when the European powers, through the Opium War and other wars, succeeded in “opening up” China, it resulted in concessions that created “treaty ports” along the coast that would be used for trading with the outside world. Those ports of course face the ocean, face east.

But the nation of China clearly faces west and has always done so. Chapter 2 of Fairbank's book begins:

The Manchu or Ch’ing dynasty that ruled China from 1644 to 1912 was the climax of a long development of relations between the settled farmers and bureaucrats within the Great Wall and the sometimes expansive and conquering nomadic tribes of the Inner Asian steppe. Chinese foreign politics from the time of the Han dynasty … had been concentrated upon the Inner Asian frontier. Tribal intrusions into the agricultural zone of North China began very early, well before the unification of 221 B.C. The Chinese state thus was born with a frontier problem and developed great skill in dealing with it in any number of ways.

Peking, the Forbidden Palace, the Great Wall – these are all testimony to a viewpoint oriented around the setting rather than the rising sun. One of the best things in the book is how the Manchus, the last of the hordes to appear outside the gates (in this case the northern gates), even though they became conquerors, in fact represented a very, very thin layer on top of Chinese society. They were, nonetheless, able to control the society which they had mastered for two and a half centuries.

One thing they could not control, however, was footbinding. The Qing emperors “many times” issued edicts against this practice, all to no avail. I was already familiar with the details of foot binding from Jung Chang’s Wild Swans. Her beautiful grandmother’s feet were, when a child, broken, mutilated, and bound, and the whole horrible process is well described. But I had not realized the extent and the antiquity of what Fairbank calls this “major erotic invention.” “First and last one may guess that at least a billion Chinese girls during the thousand-year currency of this social custom suffered the agony of footbinding and reaped its rewards of pride and ecstasy, such as they were.” Fairbank has much else of interest to say about this “achievement in Chinese social engineering.” He ends by saying that there are three remarkable things about it: that it was invented at all, that it spread so pervasively and lasted so long, and that “it was certainly ingenious how men trapped women into mutilating themselves for an ostensibly sexual purpose that had the effect of perpetuating male domination.” Fairbank says also, surprisingly, insightfully: “We are just at the beginning of understanding this phenomenon.”

Fairbank is no less enlightening on the imperial examination system, another feature of Chinese history with which it is essential to become acquainted. After telling us that the Han invented bureaucracy when Rome "was still using private individuals to be tax farmers and to handle public works,” he characterizes the system as one which involved “a dozen hurdles in the space of twenty or thirty years.” A boy began at about seven and in six years memorized the Four Books and Five Classics, 431,000 characters. In addition, he had to have a vocabulary of 8,000 to 12,000 characters, which entailed memorizing 200 a day. As for the examinations themselves, a five-day preliminary examination in calligraphy “eliminated the dunces.” Then a three-day prefectural exam which qualified him to take the four-day qualifying examination. There were strict rules about guarantors and teachers, establishing identity, and marking by number rather than name. Cheating was elaborately and effectively suppressed. Every act was monitored:

He was allowed to go to the toilet only once in the day and so kept a chamber pot under his seat. Meanwhile, the examiners were kept sequestered for days on end until the results were worked out. Cannon shots and processions began the ceremony, banquets concluded it, honor accrued to the successful. They had now qualified as licentiates and could compete in the real examination system!

Licentiate status was so desirable that it could be bought, lest “vigorous personalities” destroy the system from the outside. About a third of licentiates had purchased their place, and this was public knowledge. High officials still came up on merit, however.

The real examinations were held first in provincial capitals, then in Peking, and lastly, for the very few survivors, at the Palace. Security precautions for both candidates and examiners were “far beyond Pentagon levels.” All answer sheets were copied over by a corps of copyists, so that examiners never saw the originals, and candidates were identified only by number. 1 in 100 would pass. The men who emerged were about thirty-five years old and had spent nearly every waking day for twenty-five or so years in classical scholarship.

One of Fairbank’s more important themes is how this system was responsible for turning a highly inventive nation into a backward-looking one, one which did not want to know about progress being made in the outside world. No one who had not come through this fantastically difficult system could be respected; no idea which had not been a part of this system could be respected. The system could be corrupted, but it could not be opened up. The entire institution of education in China, moreover, was geared to this system. The West turned more and more to science, but China continued to view the meaning of education in terms of being prepped for the examination.

A key point in all this is that although plenty of rote learning was required that was merely an entrance qualification, even though it required decades to accomplish. The system demanded analytical thinking and intelligent judgment. In 1870, for example, candidates "wrote five papers: (1) on fine points of interpretation in the classics, (2) on organizational details in the twenty-four histories, (3) on the various forms of military colonies, (4) on variation is methods of selecting civil servants, and (5) on details of historical geography." The system changed over the many centuries and a Literary Examination was added, with such features as requiring the composition of sixteen lines of five-syllable verse on "Heart pure as an icy pool," with the rhyme on "heart." Waley provides further insight because Lin was interested in the latest examinations, if only because his own sons were candidates. He records news he received about these in his diary. For example, the latest Palace Examinations had required an essay on the theme that "The gentleman must make his thoughts sincere." The system spread its tentacles widely because, it appears, even mandarins who had made it to the highest level, and served on such things as the Board of Punishments, had examinations set for them. Lin cites a topic set for this Board: "Of all inanimate things, the mirror is the greatest sage."

Those of us just discovering this system, Fairbank leading us ahead, have, I would guess, the same initial impression: how odd it is that a society so elaborately and rigidly hierarchical should be based on something so seemingly fair as a regime of examinations. That only the very rich could enter this competition comes as no great surprise, but a certain flavor of fairness persists, as does its incongruity. The surprise is that fairness becomes a weapon, in a sense, against progress. What starts out as the best way to select new mandarins becomes a system for holding the entire nation back.

A striking irony, to carry this a bit further, is that the British, those very same victors in the Opium Wars because of their advanced technologies, began to suffer from a similar problem, starting at about the time of their triumph. This problem, if not the parallel with China, was brought to my attention by the BBC and its original science historian, James Burke, and revolves around a belief in the unique merits of a "classical education," in Britain's case "classical" meaning Ancient Greece and Rome. More on this in Chapter 10, below.

Although the examination system, or the failure to reform it meaningfully (Li Hongzhang in 1864 proposed unsuccessfully to add topics in science and technology), ultimately choked the imperium to death, another misconception would be that it consisted of pole vaulting events in which he whose praise of the emperor was highest would be inducted into the Hanlin Academy and given room and board in the nation's capital for the rest of his life. In fact, that wasn't the sort of performance the examiners were looking for. Critical thinking was valued, despite the heavy structural impediments of the baguwen ("eight-legged essay"), for example. Indeed, in what might be called the larger national evaluation system which extended to bureaucrats at every level, for they too sat examinations and had their performance assessed, "Criticism of Government measures", as Waley remarks, "both by the official censors and officials in general, was one of the most valued and jealously preserved aspects of Chinese administration." (He adds, however, that those censors and officials often learned about measures too late for criticism to be of any use, a problem not confined to China: "Parliament had no opportunity of expressing a view as to whether England ought to go to war with China until eight months after the war had started." Might other countries have a similar problem even today?)

* * *

The precise meaning of key terms is something which is used by Fairbank to unlock our understanding of the challenge faced by western religion in China, another important

aspect of modern Chinese history. Protestants, originally viewed as “a sect of the Buddhist type," had, as he cleverly puts it, a “term problem.”

Missionary translators were up against it: if they used the established term, usually from Buddhism, they could not make Christianity distinctive. But if they used a neologism they could be less easily understood. The problem became most acute at the central point in Christianity, the term for God. After much altercation the Catholics wound up with Lord of Heaven, some Protestants with Lord on High, and others with Divine Spirit. In fact a translation into Chinese of the Bible produced a stalemate in which the missionaries could not agree on what to call the basic kingpost of their religion.

To make matters worse, the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) was centered around a figure who claimed to be the brother of Jesus (he was, in fact, a failed candidate in the imperial examinations). His cult produced its own translation of the Bible. This helped destroy the Protestant image. “After 1864 it took a lot of explaining to reconcile a Chinese Confucian Scholar to the idea that Christianity could give him a new life.”

Converts were few. Australian G.E. Morrison, whom one source describes as “physician, journalist, traveler, author, book collector and humanist all combined,” noted the problem: “They tell the Chinese inquirer that his unconverted father, who never heard the gospel, has, like Confucius, perished eternally.” Fairbank: “A man’s conversion, in short, would condemn his father and all his line to burn in brimstone forever.”

Protestants soldiered on, however. Further insight into this can be had by reading the memoir of Paul Frillmann, discussed here in a later chapter, a Lutheran who served as chaplain to the Flying Tigers.

That’s a lot of Fairbank, and there is a lot more. Except for the reference to the December 1st Movement, everything I’ve summarized occurs in the first 128 pages.

Fairbank's treatment of the December 1st Movement (p. 243) deserves additional treatment because it deals directly with Yunnan and with Kunming.

The governor of the key province of Yunnan, which had become the airbase doorway to Free China, was able to keep Chiang Kai-shek’s secret police and troops largely out of his province until after the end of the war in 1945. As a result the Nationalist police were unable to suppress the student and faculty movement for a coalition government and against civil war at the Southwest Associated University in Kunming until the end of 1945. When a leading and patriotic faculty member, Wen I-to, was assassinated in mid-1946, the event confirmed the general alienation of Sino-liberal intellectuals from the fascist-minded KMT regime.

Chiang and his co-conspirators had, early in the war, established a People’s Political Council, a name and a concept which appears to have been a holdover from Sun Yat-sen. The Council was "purely advisory" and was intended to mobilize liberals in the war effort, but "the KMT soon took it over and prevented its being even a sounding board for liberal opinion."

The December 1st Movement was just that – a “student and faculty movement for a coalition government and against civil war.” What a difficult thing to do, though, trying to hold two mortal enemies at arm’s length and asking them to make peace and form a coalition!

[Footnote to Fairbank's point about how the Manchu tribes succeeded in controlling their new Chinese empire, overcoming the fact that they had only a tiny population of their own and represented a very thin layer of society: testimony to how few in numbers they were comes from the fact that today, only a century after their fall, the language they spoke is likely to become extinct when the last few speakers, now in their eighties, die. This doom is impending even though a fifth of the documents in China's archives from the Qing dynasty are in Manchu.]

* * *

Fairbank's book covers the whole of China and particularly the machinations surrounding the national capital, Peking, the wartime capital, Chungking, and the business capital, Shanghai. Although Yunnan is treated of on several occasions, some additional Yunnan background will be of interest. Since the establishment of the republic in 1911, Yunnan's connections with the central government had been tenuous, due to the province’s remoteness and the fact that at least half the population was non-Han Chinese. When Yuan Shikai, former republican leader, lost his head and proclaimed himself emperor of China in the December 1915, the military leaders in Yunnan, including Tang Jiyao, announced the independence of Yunnan. Tang joined his compatriots Cai E (Tsai Ao), Li Jiejun and others in this, and together their armies were able to defeat Yuan Shikai and bring about his downfall in what is called the National Protection War. Tang became military leader of the National Protection movement. After Cai E died in 1916, Tang helped his mentor Sun Yat-sen set up the Constitutional Protection Movement in 1917. He also started his own party, the People's Party, though he remained a member of the Kuomintang and even helped Sun secure his leadership position against a rebellion by Chen Jiongming and the Old Guangxi Clique.

But Tang also used opium to make money. At one point he smuggled to Shanghai opium which he had confiscated, but the famous Green Gang in that city (with whom Chiang Kai-shek later allied himself against the Communists) scuttled that operation. Tang was more successful in establishing a scheme for opium trafficking in Yunnan, handing out licenses, creating monopolies, collecting taxes, and growing the necessary poppies. He transported his opium to Haiphong, just across the border in Vietnam, and then had it shipped to a number of the coastal cities of China.

A few days after Sun's death in 1925, Tang claimed that he was Sun's successor and should be the new head of the Kuomintang. His claim was rejected. He then launched invasions of neighboring Guangxi province, where he was defeated by Li Zongren, and also of Guangdong province which had been Sun's power base - also unsuccessfully. After these failures, he did not last long and was overthrown by his subordinates Hu Ruoyu and Long Yun (aka Lung Yun).

At this point we need to know that Long Yun is a member of the Lolo ethnic minority, a section of the larger Yi minority here in Yunnan. Although ethnic, he was thoroughly sinicized through his military training and service, if in fact he needed to be. Actually, some photographs make him look as much anglicized as sinicized, for he wears round-lens glasses with thick black frames, rather like an English intellectual in spectacles provided by the National Health Service in the old days. Perhaps that is why General Stilwell, after meeting Long for the first time in Kunming April 5, 1942 wrote in his diary: "Comical little duck." (Long might have written the same about Stilwell in his diary). Long eventually became the chief figure in Yunnan, succeeding to the opium and tobacco trades which provided enormous riches. (Jonathan Spence says that Long was himself addicted to opium). Long ostensibly accepted the authority of Chiang Kai-shek’s new regime, centered in Nanking. But in fact, Long maintained his own army and a separate currency for Yunnan province.

The war brought huge changes to the province. Kunming's pre-war population was about 150,000, but in the two years following commencement of hostilities with Japan 60,000 refugees had been added to the city. Although Long Yun paid lip service to Chiang's leadership in the fight against the Japanese, he did not implement Kuomintang censorship laws. Spence says that the result was that Kunming became "a vital intellectual center," as well as the home of Lianda, the Southwest Associated Universities.

John Israel, who studied under Fairbank, is the author of the history of Lianda, and his book includes much about the warlord who ruled the province where the university found refuge.

Following the counsel of his American-trained adviser, Miao Yuntai, he developed Yunnan's tin resources and took the first steps toward industrialization under a system of state capitalism. Hence, the notion of Long as a benighted warlord - an impression held by most Lianda modernists - was somewhat out of date. He was actually one of a group of reformist military governors that included Li Zongren and Bai Chongxi in neighboring Guangxi and Yan Xishan is Shanxi, who considered their power inseparable from the political and economic development of their realms.

. . . Early in the war Long moved to identify himself with the policy of uncompromising resistance to the invader. Stopping in Kunming during his flight to Hanoi and eventual puppetdom in Nanjing, Wang Jingwei had sought Long's support, but Long blasted Wang as a rank capitulationist and won acclaim from Qian Duansheng, Lianda's respected political scientist and editor of the prestigious weekly journal Jinri pinglun (Today's Critic). Throughout the remainder of the conflict, Long cooperated with the central government in prosecuting the war while struggling to protect provincial autonomy against the Chongqing regime's growing military, political, and economic presence in Yunnan.

Long was at first nervous about the influx of almost-foreign intellectuals (the few actual foreigners were also a concern) because he had always been able to use Yunnan's remoteness from the north of China as a weapon supporting his autonomy. But he eventually reconciled himself to their presence, even showing concern for their welfare and finding benefits in associating with such accomplished and in some cases even famous individuals. Israel suggests that he also valued their frankness in comparison with the fawning yes-men who traditionally surround absolute power.

Long may have, ten years after his consolidation of power, fertilized the Lianda flower, but he was not a simple “tribal-boy-made-good.” "In 1928, during the . . . Party Purification Movement, he had executed an estimated four hundred leftists." His censors also were active from the moment Lianda arrived. They regularly found loose and accusing lips among the students writing home. Israel, who interviewed Long's son for the book, tells of one incident where Long sent police officers to deliver a "personal invitation" to the forty most offending student correspondents. They were then escorted by the police to Long's quarters. The students feared for their lives - they knew what a warlord was like! Long asked them to read their criticisms, the most serious of which was that he'd made a secret deal with the puppet Wang Jingwei, an accusation in effect of treason. After determining that the only basis the students had for the accusation was general hearsay, he admonished them to be more careful with their facts, especially since they came from the best universities in the land. "The audience was over, and the students were still alive. Overwhelmed by relief, they wept aloud and ran up to shake Long's hands and apologize."

After the war with Japan was won, Chiang sought to consolidate his hold over southwestern provinces. Prior to this, Long had even been able, in maintaining his autonomy, to go so far as to require that whenever he came to Chiang's wartime capital, Chungking, for consultation Madame Chiang be sent to Kunming as a sort of hostage until Long's safe return. But now, obeying Chiang's orders, a good part of Long Yun's private army of over 100,000 men, under the command of his cousin Lu Han, marched away, to Indo-China, to accept the surrender of Japanese forces and to hold the area down until the French could reestablish control over this portion of their empire. Chiang then ordered Long to leave Yunnan and take a face-saving job in Chungking; Long refused. "That night rifles cracked in Kunming: next morning a score of bodies lay at the South Gate," according to a contemporary news account. Long was unable to prevail, deprived as he was of his army. Ultimately, T. V. Soong, Chiang's right-hand man (and his wife’s brother), flew down to Kunming with the Kuomintang commander-in-chief, General Ho Ying-chin. The pair escorted Long Yun to Chungking where he was given a meaningless title and put under house arrest. General Lu Han, Long's former aide, took over the Yunnan government for the Generalissimo.

Long managed to flee to Hong Kong at the end of 1948, where he joined the Kuomintang Revolutionary Committee (KMT-RC), an organization opposed to Chiang. In August of the following year, after Chiang had already fled to Taiwan, Long openly declared himself in revolt against Chiang. These actions were sufficient to induce the Communist Party, after their victory, to recall Long Yun to a leadership position. He became vice-chairman of the National Defense Committee and vice-chairman of the Administrative Council of Southwestern China. He was also vice-chairman of the KMT-RC, continued as a "democratic party" under the Communist Party. Like many other distinguished figures in the Party from the previous decades, Long Yun was attacked during the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957. He had been critical of Chinese foreign aid policy (China had aided North Korea and the Viet Cong), arguing that if the living standard in the Soviet Union was so high that many ordinary workers could own their own cars, then the responsibility for foreign aid should fall on the Soviet Union, not on China. The Chinese economy was so far much less advanced. The day after his death in 1962, the Chinese government formally declared that he was not a rightist, and thus he was partially "rehabilitated." In July 1980, he was finally fully 'rehabilitated' and the Anti-Rightist Movement was declared to have been wrong.

* * *

Rock

![]() he pleasures of field work have mesmerized many a young biology student and played a determining role in their choice of career. Out of doors, the fresh air, the stars at night. Ah wilderness! And what better place than Yunnan province, one of the "biodiversity hotspots" of the world! The perfect place to enchant a student of the life sciences, with its gigantic geographic and climatic variations from cold Himalayan heights to steamy lowland, tropical forests. Here, for example, is your typical botanist out in search of rhododendrons, azaleas and other beautiful flowering plants from Yunnan:

he pleasures of field work have mesmerized many a young biology student and played a determining role in their choice of career. Out of doors, the fresh air, the stars at night. Ah wilderness! And what better place than Yunnan province, one of the "biodiversity hotspots" of the world! The perfect place to enchant a student of the life sciences, with its gigantic geographic and climatic variations from cold Himalayan heights to steamy lowland, tropical forests. Here, for example, is your typical botanist out in search of rhododendrons, azaleas and other beautiful flowering plants from Yunnan:

It was just after lunch on a mountain called San Ko when my muleman came running up to me saying that there were brigands behind the caravan. I waited until all the mules had come up and proceeded, but not very far when my men called 'brigands ahead' and at that moment the robbers opened fire on us. One of my soldiers was killed instantly. The other soldiers opened fire on the brigands, and we retreated downhill under constant fire. My handful of soldiers were really brave and kept the brigands back a bit, but they outnumbered us and pursued us. We reached the bottom of the valley, the brigands hard behind us. We had to climb a hill and, once over that hill . . . I thought we were safe. But I reckoned without the brigands. They followed us to the village of Panyiengai, which they looted and where they captured three soldiers and their guns.

Well, perhaps "typical" is not the right word for this particular botanist.

The year is 1924, ten years after Shaemus Anderson first arrived in China and eight before John Fairbank first arrived. Actually, Joseph Rock first visited China briefly in 1913, coming to live here in 1922, but today he is five days out of Kunming (which he knew as Yunnanfu) on his way north via Chengdu in Sichuan province, under contract with the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University to collect species hardy enough to survive a Massachusetts winter. Rock was born in Vienna forty years ago. His father, a manservant by trade, eventually became a sort of chief-of-staff to a Polish nobleman, Count Potocki. His mother, of Austro-Hungarian descent (she taught her son Hungarian), died when he was six. His father, superstitious and “a religious fanatic,” now wants him to become a priest, but that is not what Rock desires; instead, he wanders Europe and North Africa, supporting himself by odd jobs, including as a seaman. At one point, in Rome, he attempts the ritual visit to the Pope, but lacking a dark suit he is not allowed to join the papal audience; “from that day on he could never find a kind word for the formal trappings of any institutionalized religion,” says his biographer. In England he is diagnosed with incipient tuberculosis. Advised to seek a dry climate, he plans, in Antwerp in 1905, to go to southern France, but misses his train. Instead, that same day, he sails to the US, where he quickly picks up the local lingo and supports himself again by odd jobs, this time in NYC. In 1907, by way of Havana, Vera Cruz, San Antonio, TX, Waco, TX, L.A., and San Francisco (the earthquake was 1906), he arrives in Hawaii, age 23. Ultimately by finding work out of doors, in service of his newly and rapidly acquired botanical learning, he makes himself free of consumption.

If among autodidacts there were something akin to sainthood for the high achievers, Rock would be assured of a place in Heaven. He started teaching himself Arabic while traveling with his father, age ten, to Egypt; he continued by visiting the Prater, Vienna’s famous park, where Arab fakirs and others hung out; by sixteen he could teach it. His fascination with China began at age thirteen, when he started teaching himself Chinese characters, using the familiar index card system, which he had to conceal from his father. In his travels after leaving Vienna, he taught himself Italian, French, Greek and English (he also knew Latin from school). He also taught himself botany. He was a very good teacher because he ultimately authored The Indigenous Trees of Hawaii, became the Territory's first official botanist, and was given a position on the faculty of the University of Hawaii.

By the 1920's, however, he is seeking wider fields, fields nearer his beloved Cathay, and he starts by looking in SE Asia. He discovers a search into the jungle and sells himself as just the man to lead it - an expedition paid for by the US Department of Agriculture's Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction searching for the Chaulmoogra tree, the oil of which was an early treatment for leprosy.

* * *

One path to Rock, though it may be eccentric of me to suggest this, lies in the tale of an equally famous eccentric whose eccentricities have been dramatized in a famous film: Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo. Fitzcarraldo, played by the – there is no other word – eccentric German actor, Klaus Kinski, is located a world away, in the heart of the Amazon. The film is about Fitzcarraldo’s effort to transport a steamship over a mountain so he can use it to exploit rubber trees in the Amazon basin. The film is based on the real-life rubber baron Carlos Fitzcarrald (1872-1897), of Peruvian-American ancestry.

Perhaps the best-known scene in the film is the one in which Fitzcarraldo is cruising down the Amazon playing Caruso recordings on his Victrola and broadcasting them at loudest volume to the surrounding jungle. (The film opens with another eccentric and memorable scene: Fitzcarraldo making his way to a performance in Manaus at the preposterously ostentatious opera house built by the rubber barons as far away from civilization as it was possible to get. An aged and heavily made-up Sarah Bernhardt is performing as Lucia in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, with Caruso himself singing Edgardo. Sarah was of course a diva of the dramatic arts, not a diva of the musical theater – no matter, she is the one the rubber barons want: she is famous, the most famous actress in the world, and all she has to do is lip synch the words sung by another, no matter how old she is.)

Not long after Fitzcarraldo had made Caruso and Verdi known to the river and the forest, Joseph Rock was playing Caruso in mountain villages in Yunnan. Caruso echoing in the mountains was only one of his many eccentricities. His goals involve transport over mountains, some of the highest in the world, but have nothing to do with steamships: he seeks botanical and anthropological knowledge by trekking up there.

Rock departed Hawaii for Burma, but ended up, after chasing a tree, in quite a different country, high in the mountains, and north of the border - in China, in Yunnan, in Lijiang, center of the Naxi (then Na-Khi) culture. Lijiang is northwest of Kunming about 800 kilometers. His interests ultimately turned there from botany to anthropology, and specifically to the Naxi people themselves.

Although this is better understood today than it was back when Rock first arrived, the label “Naxi” has been conferred by the government on a number of related but rather different groups. This lumping of different cultures did not just occur among the Naxi. In fact, when the government first announced in the 1950s that it would recognize ethnic minorities, 260 groups from Yunnan proposed themselves. The government accepted 25; apples and oranges, necessarily, were not always distinguished. As for the Naxi, two groups merit special discrimination: the Naxi of Lijiang and the Mosuo (or Moso) of Lugu Lake.

Rock’s main interest and contact was with the much larger Naxi per se, among whom he lived. The lake which the Mosuo are centered around is about 6 hours, on modern roads, NE of Lijiang. If Rock’s attention was devoted to the Naxi, modern anthropologists seem more fascinated with the Mosuo because their social practices are so very different from those which characterized the Han Chinese for so long, including footbinding and patriarchy. The Mosuo back in the 1920s were a paradigm matrilineal society. Property passed down the female line (families with no girl adopted one). Females resided in their mother’s house, and each female’s children, male and female, took the mother’s surname. There was apparently no term for “father.” After a puberty ceremony came an extensive system of Azhu, trial marriages. The grandmother or the mother ran the household; each female had her own room in which to receive her Azhu partners. Young men had no such room, however, and if they did not sleep in an Azhu’s house, stayed in the room for old men at their own family’s house. Young men could have several Azhu partners at the same time and females could do the same.

The Naxi capital, Lijiang, is an ancient and graceful city built of wood. It is now a World Heritage Site, but whether this designation helps protect Lijiang or increases the ravages of tourism is open to debate. The hordes Rock had to deal with in Lijiang’s environs, however, were quite different, and better armed: religious armies and bandits. Rock soldiered on despite all. He continued to collect and identify many thousands of plant specimens in the region and dutifully send them to the US. That famous world traveler, so preoccupied with why people travel, Bruce Chatwin, wrote a terrific essay about all this, “Rock’s World.” Chatwin tells that Rock is famous for the half-mile long “cavalcades” which he assembled and led for his botanizing. In the field, his table was set with silver, and he ate off of gold plate. He had a portable bathtub, made of canvas, purchased (as was his tent) from Abercrombie & Fitch, which was filled with heated water for his bath. He traveled, as Chatwin says, "en prince." He was supported by the National Geographic Society as well as by Harvard and the Smithsonian.

* * *

Almost all accounts of Rock’s life stress his long career centered in Lijiang, botanizing and anthropologizing, near the town itself and during faraway journeys launched from there. His earliest significant publication, the National Geographic article on his pursuit of the Chaulmoogra tree, however, is less discussed but in fact reveals much about his style - and how he uses this style to make money. The article begins with a bit of science about the acids contained in the oil of the fruit of the tree. Then there is the king in the tree.

[The natives of SE Asia] relate in their pre-Buddhistic legendary history that one of the Burmese kings exiled himself voluntarily and retired into the jungles, making a hollow tree his abode. Here he partook of the fruits and leaves of the Kalaw tree (Taraktogenos Kurzii), and in time his health was restored.

Rock disembarks in Singapore and takes a train to Bangkok five days away - five not because of distance, but because the train only runs during the day and the nights must be spent in "indifferent rest-houses." "Through the courtesy of our American Minister, my host while in Bangkok, I was permitted by the Royal Siamese household to photograph the interiors of the various wats, even the most sacred Wat Phra Keo, with its Emerald Buddha." National Geographic’s readers love pictures (the article has 30 in all, plus a map of SE Asia).

Rock moves on 700 km (435 miles) to the north, to Chiengmai (Chiang Mai). Many areas of the world, including Kunming, suffer from drought. Rock, however, stumbles upon a rainmaker in Chiengmai:

We spied a long, narrow box in which was a roll about twenty-five feet long and fifteen feet wide, on which was painted the figure of a huge Buddha on a lotus flower. We were informed by our friendly priest that in times of severe drought this picture is taken to the top of Doi Sootep, a sacred mountain, where a magnificent wat was erected many years ago, and there, to the accompaniment of incantations, it is held on high by priests, and invariably rain descends to refresh man and beast and save the rice crops.

Rock is not going to miss the opportunity to visit this sacred mountain. The road leads through picturesque remains of the ancient city and mausoleums of Lao (in fact Northern Thai) princes and kings. Doi Sootep is topped by a “magnificent wat,” visible from any point in the valley.

What a glorious approach to this wat! No stone stairway lined by marble pillars or way side shrines, but living columns of pines festooned and garlanded with sweet-scented orchids and vines, the steps covered with a living carpet of velvet moss; no organ played by human hands, but gentle breezes whispering in the trees and a chorus provided by feathered songsters whose abode is in the mighty fronded canopy surrounding this hallowed spot.

There are also tall chestnut trees, not affected by blight. He has his people collect many chestnuts to bring back to the US, where blight is severe. The one downer in all this is the rain, “which brought the leeches out and made walking through the forest very disagreeable.”

The pursuit of the Chaulmoogra begins in earnest with a river journey which will connect him to an overland route to Moulmein, Burma. Rock recounts local legends about the landscape along his way, including a beautiful princess on horseback leaping to her death. The scenery is gorgeous, but his party is delayed by morning fog, 41 rapids, and by frequently running into sandbars. At one point, in frustration, he jumps into the river and swims ahead, only to be told the river is infested with crocodiles.

Our next camp was near Pa Khar, where elephants kept me awake during the night. They were only breaking bamboo for food, but the noise resembled machine-gun fire. Early in the morning I climbed the hill side to collect botanical specimens, but I was soon forced to retreat, owing to the unexpected appearance of a bear.

More of this on the overland:

After reaching Raheng, we crossed glorious mountain ranges, covered with dense tropical forests of trees 150 or more feet in height, under whose protecting crowns we spent the nights. Sometimes we did not sleep with a sense of security, for these regions are inhabited by tigers, leopards, and snakes.

Just what readers of the Geographic want to hear.

On the Road to Mandalay, usually heard sung by Sinatra, starts: "By the old Moulmein Pagoda/Looking eastward to the sea/There's a Burma broad a settin'/And I know she thinks of me." The song was published in 1907, so Rock might have heard it (likewise readers of the Geographic; at any rate, he has now made it to Moulmein, a feat which included swimming the Salwin (Salween) River. Crocodiles are not mentioned. He arrives on Christmas Eve, and Christmas Day is spent with, of course, missionaries. A train then to Paung, between Moulmein and Rangoon, then by bullock cart, along with his interpreter, cook, and boy, arriving at the small village of Oktada in Karen state, where he sleeps out under a tree “despite the fact that my companions swore that the woods were infested with tigers and other wild animals.” Three days of climbing hills in the area produce fruit/seeds of a tree very similar to Chaulmoogra, but not the real thing. Thus, a train all the long way to a town very near Mandalay and then another train “over a semi-desert region to dusty, dirty Monywa, on the upper Chindwin River.” To “dusty, dirty” he adds “dreadful.” “Kalaw” is the local name for Chaulmoogra, and though Monywa is unpleasant, he finds Kalaw seeds in the fly-covered bazaar and is told they come from up north.

The river takes him north, though again there are problems with the morning fog and sandbars. Colorful native costumes and peculiar craft, one with a living tree for a flagstaff, enliven the journey which ends at Kalewa, “a bazaar town prettily situated on an elevated tongue of land at the junction of the Myttha and the Chindwin.” But he presses on to Mawlaik, the new government seat of the Chindwin district: “newly laid out, [it] possesses a circuit-house the like of which is found nowhere in Burma. It is a comfortable building with spacious verandas overlooking the Chindwin and the jungle on the opposite side of the river. The hospital, with its modern equipment, would be a credit to any American city.”

But the Chaulmoogras are still several days’ journey further on. He obtains an official letter from the government to use with local headmen, and paddles a dugout canoe up the Chindwin. He meets a headman, shows him the letter, and soon he has, to carry his kit, just what he has wanted since he was a boy:

A string of coolies, some twenty or more, mostly women with naked children on their hips and backs, and botanical blotters, a cot, or whatever they happened to pick out, balanced on their heads, marched through dale and over hill for the mere pittance of one anna (two cents or less) a mile.

Two days on they reach the village of Khoung Kyew - and several miles beyond that he finds his first genuine Chaulmoogra trees. Alas, no fruit! Maybe further on, at Kyokta. Five or six miles still further on beyond Kyokta, along a dry creek bed, accompanied by 36 coolies, the Chaulmoogra forests are found,and seed-collecting begins. Though:

When we reached the stream bed up which we had come a few hours previously, we found that a large tiger had followed us into the jungle, for there were its footprints so clear and distinct that I stopped and photographed them (see page 271) [of the Geographic article].

Although the party makes it back to Kyokta safely, this tiger claims victims among the womenfolk and children left alone in a hut in the jungle by two of the coolies.

We found that, owing to the cold night, the women, living with two children, had constructed a hut of paddy or rice straw directly on the ground, with only one small opening. In this hut were three women, a two- year-old girl, and the five-year-old boy [who had informed the village]. When the tiger had entered the hut, there was no escape. Short work was made of the helpless victims.

One badly injured woman was still alive and born to safety (alas, she later dies). “But what was to be done about the tiger? We had no arms save a Colt automatic, so we decided to build a trap” - and bait it with one of the dead women!

Rock is invited to spend the night in a small wooden temple at the feet of Buddha.

To sleep was unthinkable. It began to rain, the thunder rolled, and weird lightning effects added height to the somber monarchs of the forest. Crash followed crash and— what! listen! —the trampling and trumpeting of elephants, wild cries and shouts of confusion! I did not know till next morning what had happened. A herd of wild elephants ventured to the outskirts of this doomed village and made short work of the flimsy houses and rice barns. Like a cyclone, they swept over the place and, not satisfied with destroying the huts, devoured the recently harvested rice.

Here, of course, the Geographic reader is getting what he or she paid for. The tiger is now in the trap and Rock rushes to the scene: “The captured creature's rage was terrible to behold. Only a few minutes and the brute was no more, for 20 spears ended its savage existence.” There is, of course, the mandatory picture of the deceased tiger suspended from two bamboo poles carried on the shoulders of four men.

* * *

Rock romanticized the Nakhi, calling them Simple Children of Nature, Noble Savages, and crediting them with more innocence than they merited: he underestimated the mystique of his fair complexion and the power of his money. He lived like a potentate among them, surrounded by the precious artifacts accumulated in his expeditions, solid gold dinner plates, for example, a gift from the ruler of Muli, books, and his western gadgets including a battery-powered phonograph on which he played arias rendered by Caruso and Melba.

So writes his biographer, Stephanne B. Sutton in In China’s Border Provinces: The Turbulent Career of Joseph Rock, Botanist-Explorer (Hastings House, New York 1974). One of the compelling things about Rock is his long tenure in China, in a single province, much of it in a small village outside of historic Lijiang. (His house is still there, unfurnished, minimally curated, visited by the occasional tourist, including me). Shaemus Anderson’s tenure in China was also long, but his stays in Yunnan were quite brief compared to Rock’s. Fairbank’s longest tenure in China, among several, was his first, from 1932 to 1936, and though he visited Yunnan, his residence was mainly in, as they were then called, Peking and Chungking.

To be sure, Rock traveled much, including not only many trips in China out of Yunnan but also trips to the US and to Europe, but he was anchored in China at the grass roots level in a way in which neither Anderson nor Fairbank, nor any of the other authors treated in depth here were. Here are some of Rock’s articles (some titles abbreviated) for the Geographic:

"Banishing the Devil of Disease Among the Nashi: Weird Ceremonies Performed by an Aboriginal Tribe in the Heart of Yunnan Province" (1924)

"Land of the Yellow Lama: Strange Kingdom of Muli, Beyond the Likiang Snow Range of Yunnan, China" (1924)

"Experiences of a Lone Geographer: through Brigand-Infested China En Route to the Amne Machin Range, Tibet" (1925)

"Through the Great River Trenches of Asia: Yangtze, Mekong, and Salwin" (1926)

"Life among the Lamas of Choni: Describing the Mystery Plays and Butter Festival in the Monastery of an Almost Unknown Tibetan Principality in Kansu Province" (1928)

"Seeking the Mountains of Mystery: An Expedition on the China-Tibet Frontier to the Unexplored Amnyi Machen range, One of Whose Peaks Rivals Everest" (1930)

"Glories of the Minya Konka: Magnificent Snow Peaks of China-Tibetan" (1930)

"Konka Risumgongba, Holy Mountain of the Outlaws" (1931)

Only someone who has experienced China at the grassroots level could present a portfolio such as this - not to mention his books, The Ancient Nakhi Kingdom of South-West China 2 vols. (Harvard, 1948) and a posthumously published A Nakhi-English Encyclopedic Dictionary (Rome: I.M.E.O., 1963).

As the articles indicate, National Geographic became Rock’s principal source of financial support when the contract with the Department of Agriculture ended early in 1923. One of the things Rock wants to do first in 1924 is visit the exotic "kingdom" of Muli, just beyond the Yunnan border with Sichuan. The previous king, who had warned him two years before not to come, on grounds there were too many bandits, had died, and Rock now decides to risk it. Accompanied by ten Naxi soldiers armed with Austrian muzzleloaders, vintage 1857, who show up at the last moment in response to Rock’s threat to depart on his own, Rock sets off with three horses, eleven mules and men to tend them, and his personal servants. It takes eleven cold days. The distance is only about the same as between Philadelphia and NYC, but the terrain is extremely mountainous, the trails poor, and blizzards slow the troop’s progress.

The king, whose secretary, a lama, has shown Rock to a comfortable house, is anxious to meet this foreigner. Ushered into the presence, Rock finds Chote Chaba, a head taller than he and weighing around 300 pounds (136 kg). Kings do not lift fingers, or anything else, so are likely to grow fat. The king even wants to know who rules China, an emperor or a president? Were whites still warring? Can Rock’s field glasses see through mountains? Tell me about these photos I have collected. Would you feel my pulse and tell me how long I have to live? Lamas stand by, heads bowed, through all this, stand because they are forbidden to sit in the presence. Rock is served the famous yak buttered tea. On golden plates (Muli’s streams have gold) comes well-aged yak cheese “interspersed with hair.” All that is disgusting, but a good article can be had out of it. Chote Chaba’s parting gifts a week later include a dried leg of mutton, more yak cheese (this time full of maggots), and a wormy ham.

* * *

The brigand-filled quotation at the outset here concerns a journey which took place at a time when all hell had broken loose, not for the first time, in China. Tibetans are beheading Moslems, and Moslems are beheading Tibetans. Warlord is slaughtering warlord, and peasants are conscripted and used as if they were Minié balls to be rammed down a muzzleloader. Brigands roam all over the place. Han Chinese power players are lurking around, hoping to find an opening, and threatening all.

Back now in the US after his visit to Muli, Rock negotiates a contract with Charles Sprague Sargent, founder of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, to botanize two very remote mountain ranges in NW China - the Amnyi Machen (Amne Machin) and the Richtofen (Nan Shan) - and to collect seeds from species, especially conifers, that can withstand a Massachusetts winter. Contract in hand, Rock arrives back in Shanghai and makes his way to Kunming, which he departs on December 13, 1924. Rock is traveling this time with the protection of forty soldiers and is attacked on the fifth day out, then again on the sixth. He proceeds nonetheless, minus the one killed and a further three captured at Panyiengai. At Yicheshun, he gains another thirty-five soldiers, but they quickly report that the brigands number around 600. Rock retreats to a dilapidated temple and fears the worse. But the anticipated dawn attack fails to materialize, and Rock’s troops move on. A couple of days later his two contingents of soldiers begin to fight with each other. Only by physically interposing his person between the two is he able to stop this. Near Chaotung (Zhaotong) in far NE Yunnan he is met by 250 soldiers sent out by the magistrate to rescue him. Rock hates Zhaotong: "It made me sick and very uncomfortable." It starts to snow, delaying him for five days.