Green Lake: Reflections from the Surface of China

5/ Three Types of Trips, and Trifles

![]() mong Green Lake’s virtues is its proximity to other places in Yunnan that exhibit the province’s geographic, ethnic, and biological diversity. I wrote about our family’s trip to Jinghong, capital of Yunnan’s fascinating Xishuangbanna prefecture, not long after it occurred, but that account got lost when Yahoo made an executive decision to clear out older emails from its accounts. (Caused a huge migration to gmail, no doubt). This trip is worth recalling now because it is about a part of Yunnan which is less traveled than others, particularly back then.

mong Green Lake’s virtues is its proximity to other places in Yunnan that exhibit the province’s geographic, ethnic, and biological diversity. I wrote about our family’s trip to Jinghong, capital of Yunnan’s fascinating Xishuangbanna prefecture, not long after it occurred, but that account got lost when Yahoo made an executive decision to clear out older emails from its accounts. (Caused a huge migration to gmail, no doubt). This trip is worth recalling now because it is about a part of Yunnan which is less traveled than others, particularly back then.

Almost all of Yunnan is south of the northernmost border of Myanmar. Few people outside China seem to realize this, and many in China are unaware of it as well, I would guess. A portion of southern Yunnan is south of the very northern borders of Laos and Vietnam, both of which are considered to be tropical countries. All this makes Yunnan in some sense a part of SE Asia as well as China. Jinghong is located in the portion which is south of the northern borders of Laos and Vietnam and is roughly on the same latitude as Mandalay, Myanmar.

In February, as Kunming was becoming cooler (not by much, though), we decided to fly down to the tropical part of Yunnan and experience a week there. The average high in Jinghong in February is about 84° F (28.6° C), only a few degrees cooler than in August, though rainfall is significantly lower. We booked a hotel recommended by a friend who had been there recently and bought airline tickets. We could not take our dog, Shanghai, with us of course, so we arranged for one of our friends of whom Shanghai was especially fond, Ming, to take care of her while we were away. We then took the short flight down to Jinghong.

The night before we left we used one of our locally-bought DVDs and watched a very odd movie, Adaptation, starring Nicolas Cage. The producers of this movie bought the rights to The Orchid Thief by Susan Orlean, a non-fiction book. I had read the book and enjoyed it very much. It is a Florida story: such things as sales to northerners of lots which are in fact under water feature prominently, as does the history of the Seminole Indians. The story was sparked by a small article in the Herald which Orlean had read while visiting relatives in Miami. A young man had been arrested for collecting orchids in the Fakahatchee Strand preserve. The book tells how this unlikely individual came to be one of the world’s experts on orchids without any formal education in the subject. That is engrossing, but more than that the book is a history of orchid collecting itself, a vast worldwide enterprise -- so great is our love of orchids -- beginning with the English at the height of their empire in the 19th Century. The movie oddly discards almost all of this fascinating material in favor of a story about how difficult it is to write a screenplay about such a story. Cage is a tortured soul. One brief attempt, however, is made to tell a bit of the history of collecting. A thick mist fills the screen. A narrator uses the word “dangerous.” A collector-explorer is wading through a swamp. Voices are heard just as the orchid is sighted in a patch of sunlight. Much crashing about as the explorer is killed by natives. An empty row boat is seen drifting aimlessly in a pool. Beneath that final scene appears one word: Xishuangbanna.

The landscape below the plane as it circles around in its lengthy landing pattern is stunning. It is not the landscape’s beauty which is stunning, because it is far from beautiful: it is because a huge area looks exactly like one of those bristle mats that people put in front of their doors, so you can wipe the soles of your shoes of dirt before entering. This vast area was all tropical rainforest fifty years before we arrived. The story I have heard is that that forest was cut down because the Chinese economy needed rubber, and those opposed to Mao’s takeover of China were making it difficult for China to obtain the rubber it needed. Again, Yunnan’s southerly position within the Middle Kingdom was key: there really was no other place sufficiently tropical and sufficiently large where rubber could be grown on the scale needed. Hainan island is even further south, and it, too, began to be populated with rubber plantations, but Yunnan is vastly larger. Exit rainforest and its biological diversity; enter rubber plantations and monoculture and the appearance of a doormat. Mao didn’t just want rubber, he wanted self-sufficiency in rubber.

In fact, Xishuangbanna does today have some nature preserves, created, I believe, after the overwhelming effect of the transformation to rubber plantations had sunk in. These preserves were created out of what was left of the primary forest once the vast majority of it had been put to the axe. Typically, such preserves are on the steeper slopes which were passed by in the initial conversion as too difficult to access efficiently. We visited and stayed at one of them, a botanic garden rather than a preserve per se, during our Jinghong week.

We landed in the sunny afternoon, exited under a sign which read “Peculiar Chamnel,” got a taxi to the Golden Banna, and then walked around. Susan had visited Thailand and Cambodia a number of times before this and pointed out the styles of clothing and of buildings here which were distinctively SE Asian. These were numerous and hard to miss, but what surprised us more in some respects was the amount of new construction and renovation. Jinghong was transforming itself from a remote town to a tourist and second-home destination (second-apartment, in fact, because the new units were all in ten-story tall white apartment buildings).

Our hotel had a large swimming pool in its interior courtyard. The hotel itself was a few blocks away from the beginning of the downtown, was fairly new, and was in a bland modern style. The rooms were comfortable enough, but after the fog burned off and the sun heated everything up, it was the swimming pool which was inviting. We soon found, however, that the pool was ice cold since no attempt was made to retain any of the day’s warming effect after the sun went down. Jinghong’s January lows at night are 53° F (11.6° C).

On our first morning in Jinghong we awoke to a city smothered in thick fog. This proved to be a daily phenomenon, one which we were told occurs throughout most of the year. The fog is in part due to Jinghong’s lower elevation: Jinghong is at about 1800 ft (558 m) above sea level, whereas Kunming’s elevation is almost three times that. It burns off fairly quickly, despite its density, which apparently has been diminished to a degree by the rise of the rubber plantations. The fog is a characteristic of the ecosystem here, and the plantations have altered this characteristic as well as many others.

We set out that evening to find the Mekong Café, which had been recommended to us by a number of friends in Kunming. We walked past a couple of other recommended places to eventually find the café on the second floor above a busy street, an open-air structure under a Thai-style wooden roof. Part of the pleasure of the place is watching the street below: an orange-robed monk stepping down from a bus, women carrying things suspended fore and aft from their long bong-bong boards (as a student of mine called them), adorable children holding the hands of their grandparents, though perhaps the most exotic creatures below are the Western backpackers with rings through their lips. Not all of the people who frequent the café are backpackers, though. On one visit we encountered a group of young women from the famous Miss Porter’s School in Connecticut. Miss Porter’s is an expensive prep school, known long ago as a “finishing school” (a phrase I have always found amusing), ranked as the number one boarding school for girls by US News. It was founded in 1843 by the educational reformer Sarah Porter, a woman who wanted chemistry, botany, geology and other sciences to be in the curriculum. Perhaps its most famous alumna is Jackie Kennedy, though Oprah Winfrey’s niece graduated from the school in 1994. Oprah was the commencement speaker that year and subsequently became deeply involved with the school. At any rate, here were about ten of these young women upstairs at the Mekong Café in Jinghong, all very pleasant and all very interested to find others from the home country. The school believes that travel broadens. It has a Student Year Abroad Program which includes China.

The food at the Mekong Café included a number of western dishes but was mainly what I will call Thai-style dishes, though no doubt more knowledgeable restaurant critics would have more precise names for them. At any rate, they were all very good. The last night we were there we met the owner, Vicky, a member of Xishuangbanna’s Hani minority (the prefecture has at least 13 recognized minorities) who grew up in a small village outside of Puer, the famous tea town I would pass through on our way down to Jinghong by car on a subsequent visit. She had been away and had just returned to Jinghong. I think I inquired about the extensive collection of jazz CD’s that the cafe had (I was also surprised to find a biography of California poet, Robinson Jeffers), and she told me that that was because she was married to a German.

The Lancang River slices through Jinghong, though most of the city is on the west side of the river. The Lancang flows SE to Laos and changes its name to the Mekong River there. It is a broad, powerful river, crossed in Jinghong by a modern bridge full of cars, trucks and buses. We crossed one time just to see what was over there but did not find much. Susan joined a trip on a large raft-like boat at one point and spent an afternoon on the river.

The two rural counties which are on either side of Jinghong are Menghai and Mengla. Within the latter lies the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden. We wanted to see that, and since it includes some motel accommodations arranged to stay there for two nights. The trip out to XTBG by bus takes more than an hour and was interesting for a number of reasons. One was that it gave us the opportunity to pass through portions of some of the rubber plantations, to see at ground level some of the bristles on the doormat we had seen from the sky. Row after row of rubber trees, tall enough that workers had no trouble walking under them, all of this making a dark monotonous “forest.” Another was that we passed one of the entrances to the Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve, one of those preserves created (in 1958, promoted to national level in 1986) in the aftermath of the transformation to rubber plantations. Still another was that on a particularly sharp U-curve we looked out the window of the bus to see a bicyclist coming towards us, our German friend from The Box pub/restaurant in Kunming. He is a very good football player, by the way, and is the star of the expat team in Kunming; obviously, long bicycle rides help him stay in shape.

The bus let us off in a dusty hamlet across a river from XTBG, which we accessed over a footbridge. The contrast between the hamlet and the lush botanical garden was striking. XTBG is an institution of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. It mainly serves the purpose of research in tropical forest ecology, though it also has related purposes included among which are conservation, education, specialized agriculture, germplasm/seed bank, biomolecular research, even public awareness through limited tourism. The site here in Mengla consists of 11.25 sq km (4.34 sq miles) and consists of over thirty “living collections” of altogether more than 13,000 species. The living collections are basically gardens within the garden that visitors can tour, and which represent different ecosystems within Yunnan. XTBG is a big operation, containing office space and research facilities for hundreds of researchers, including numerous graduate students working on a PhD.

We wandered about and enjoyed ourselves in this beautiful environment. The day was hot, the flowers numerous. Back at the motel, there were buses waiting for the tour groups they had transported for the day out here to return for the drive back to Jinghong. We were staying the night, however, and found that there was a good restaurant right on the grounds where we had a very nice dinner. The next day I concerned myself with birds. Although XTBG is mainly about plants, certain eminently worthwhile birds from the area frequent the grounds. Never one to let a gorgeous creature stand between me and a good time, I particularly want to pursue a sunbird.

Sunbirds are, indeed, gorgeous creatures:

small, slender passerines from the Old World, usually with downward-curved bills. Many are brightly coloured, often with iridescent feathers, particularly in the males. Many species also have especially long tail feathers. Their range extends from Africa to Australia, across Madagascar, Egypt, Iran, Yemen, southern China, the Indian subcontinent, the Indochinese peninsulas, the Philippines, Southeast Asia and the surrounding Pacific islands, and the uppermost part of northern Australia. [Wikipedia]

“Southern China” and “Southeast Asia” are the key words here, once you get past the bright colors and the iridescence. If I am going to see a sunbird it is likely to be at XTBG. I have brought my binoculars.

There was considerably less fog at XTBG in the morning than there had been in Jinghong, at least on this particular morning, a good thing because I wanted to get out early. The forest awakening is always attractive, of course, a plethora of sounds and scents. I did not really know where to look but thought I would try my luck just strolling through the living collections. The first unusual bird I managed to spy was not a sunbird but a Coppersmith barbet. Wow! What a gorgeous creature!

The beauty of this bird which is about half the size of a pigeon is said to lie in the head and throat -- think of it as wearing a black knit cap such as a bank robber might wear but cut back to reveal a substantial crimson forehead and yellow in a large circle around the eyes and on the throat. Below that more crimson in a broad necklace, and below that a lesser amount of yellow similarly configured. I think the feet are beautiful, too, bright red and all the brighter because they appear directly below a drab front. Coppersmiths are said to be “fond of sunning themselves in the morning on bare top branches of tall trees, often flitting about to sit next to each other,” and indeed that was how I found this bird. “Coppersmith” comes from the rapid tunk . . . tunk . . . tunk call, reminiscent of a smith working copper. I am especially fond of fresh figs, and so is this bird.

The next bird I managed to find was a Long-tailed shrike. Shrikes are famous for impaling prey such as lizards or small rodents on thorns or spikes in a nearby bush -- after eating the head or the brain. This bird had a gray head and back, a black mask, a narrow, long black tail, and a rusty or rufous rump and flanks. I had now seen a paradigm of fruit-eating and a paradigm of meat-eating.

But still no sunbird. I saw a number of the birds I regularly see in Kunming, but still no sunbird. Eventually I found an odd little corner, not far from a maintenance yard where I saw a flash of red. A bit more pursuit and my binoculars magnified the Crimson sunbird in a small tree in front of me. The bird is tiny, smaller than a House sparrow, but hard to miss if you are in the right place. This was an adult male. Imagine a man wearing a three-piece suit with one of those old-fashioned vests (as in waistcoat), the top of which is a very deep U. Now imagine his entire head, throat, and chest a bright crimson. Add a thin, down-curved sickle-shaped bill (the bird feeds on nectar) from the base of which proceeds a black line in the shape of Salvador Dali’s moustache. The back is dark, some say maroon, the rump yellow, the belly dark grayish olive. End with a long greenish-blue tail. What a gorgeous creature!

* * *

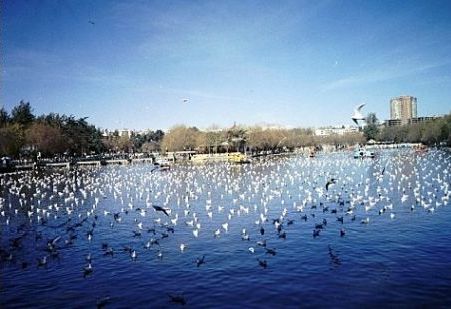

Here is another type of trip. Although I pass through Green Lake park as often as I can, I am sometimes in more of a hurry than other times, even though I am taking the long way to my office. This morning I was in more of a hurry than the other people strolling along there, particularly in the area where the walkway narrows a bit as it passes between the little lagoon where kids can shoot lasers from submarine-like pedal boats at “mines” and where there is an entrance to the interior koi ponds. Actually, directly across from the submarines is another part of the main lake where family-size paddle boats, sans lasers, are tied up. There is a grass-covered strip at that point between the walkway and the wall that bounds that part of the lake, a wall which is just above the level of the lake. This strip has posts supporting a sheet metal canopy that extends out over the boats aways.

A group of four elderly people were directly in front of me and several families in front of them, all enjoying the day. I decided that rather than zig to my left to pass the four, then zig to my right to pass the first family, then another zig left -- and so on -- I would go to my right and along the edge of the water by the paddle boats. This meant having to squeeze past the posts, but I’d done that before. This time, however, I tripped and fell into the lake.

The water was not deep, only up to about my waist. Nor was it very cold. The splash, of course, caused people to turn and look at this laowai in the lake. They had to be quick, however, because I was up and out in just a few seconds. With egg on my face, and a rather squooshy stride, I walked back to my apartment, which was fortunately not far away, and changed clothes.

* * *

Kunming, as I’ve mentioned before, has good pizza and pasta. That is only to be expected, given the universal appeal of these foods and the simplicity with which they can be made. Tomatoes, for example, are abundant here and have been incorporated into a number of local dishes – stir-fried tomato and eggs; tomato and tofu; and so on. So, some very familiar things to any Westerner are to be found here in the capital of Yunnan Province. But German music?

I recently attended a performance here by Max Raabe and his Palaster Orchester in the university’s auditorium. Max has recreated a cabaret orchestra from 1920’s and 1930’s Berlin. There are eleven men dressed in tuxedoes, plus a statuesque blonde woman in a magenta evening gown who plays the violin. For the first act, the men are dressed in white tuxedoes, except for Max, a tall slim man with light-colored slicked-back hair (naturlich) who is dressed in a black tux. Max does most of the singing, aided now and then mainly by the four guys who play various types of saxophone. He sings, of course, in German, except for certain American classics. The first act:

Bilbao

Bei mir bist du schoen

Die drei kleinen schweinchen (three sax guys with pigs’ noses)

I’m singing in the rain

Das gibt’s nur einmal

Cheek to cheek

Am Amazonas

Over my shoulder

Salome (a fox trot)

Mein gorilla

For the second act, the guys come out in black tuxes, the blonde has a sparkly light green dress, and Max has white tie and tails. The program:

Wochenend und Sonnenschein

Coubanakan (sung in Spanish)

Night and day

Chinesisches lied (Max memorized some Chinese; much appreciated)

Wir sind von kopf bis fuss auf liebe eingestellt

Dein ist mein ganzes herz

Brazil

Amalie (a fox trot)

Avalon

Dort tanzt Lulu (a waltz)

Cosi Cosa (he mentioned Mario Lanza in his introduction)

(I feel confident of my German spellings here because the program from which I took them bears the logo of the “Consulate General of the Federal Republic of Germany, Chengdu”).

The audience loved all this, and so did I. There were but ten of us foreigners in an audience of perhaps 500 people. The 500 demanded, and got, an encore.

Actually, one of the reasons I loved it was that it came as light relief from some marathon sessions with The Ring of the Nibelungen. Looking through the classical music section of one of my favorite DVD stores here, I noticed a box labeled “Ring of the Nibelungen.” The price was 42 kuai. 8 kuai (give or take a jiao or two) = 1 USD. I bought it, thinking this was some obscure German opera company’s production – but what can you lose for 42 kuai? Closer inspection of the box on the way home showed “The 8th Beijing Music Festival,” which meant nothing to me (and still means nothing to me). Also: “Patrice Chereau’s Centenary Production Filmed at Bayreuth” and “conducted by Pierre Boulez” -- now that’s more like it!

In fact, it turned out to be none of the above. (This is not unusual in Kunming, where the back of the little folder the DVD comes in sometimes lists the cast and crew from an entirely different movie). What I had in fact in my sweaty little hand was the complete recording – eight DVD’s – of the performances by the Metropolitan Opera which were broadcast on PBS over a period of years in the late eighties, early nineties. Pure gold. Siegfried Jerusalem is, of course, Siegfried. Hildegard Behrens is Brunnhilde. James Morris is Wotan. Jessye Norman is Sieglinde. Christa Ludvig is Fricka. Etc, etc. All conducted by Jimmy Levine. The production designer is Gunther Schneider-Siemssen, not so inventive as Patrice Chereau, and faulted by some critics for taking such a traditional approach, but terrific nonetheless. I could go on. But all I will say is that there is something like 24 hours of German opera here and watching all this in the eternal sun of a Kunming spring is -- blissful.

* * *

there's a wild mandarin duck on green lake right now, actually both the male and the female

the male is not afraid of people and comes close to shore .. he is fascinating to watch not just because he is so preposterously beautiful but because he is just like a little wind-up toy .. he closes and opens his eyes periodically, tips his bill down into the water (raising the feathers on the back of his head), raises his bill to let the water run into his throat, makes a sort of whirring sound, and turns around in the water

the female stands off from him watching all this with a sort of eerie fascination

So, I emailed friends. The two most beautiful ducks are the Mandarin and the North American wood duck. Turns out they, though they do not look alike, are in fact cousins, the only two members of the genus Aix, a name Aristotle used for a diving bird which remains unknown -- though it was neither the Mandarin nor the wood duck because the former is endemic to far east Asia and the latter to North America.

The Mandarin is more showy, the wood duck more elegant. The Mandarin drake (the female is drab) has a red bill, from the base of which proceeds over its head a long blue, green and copper stripe, actually a crest, at least at the back. There is a large white crescent covering the forehead-temple-upper-cheek area (highlighting the dark eye), then below all that white a rust-colored patch with elongated feathers (silver white edges to each feather) that seem like mutton-chop whiskers gone berserk. The breast is a beautiful purple with two vertical white bars; the flanks are tan, the underside white, the feet orange. Two orange, squared-off rectangles protrude above the back on each side, sometime described as "sails." This is the male, of course, before he goes into winter’s eclipse plumage.

Chinese refer to Mandarins as yuanyang, yuan being the male and yang the female. They are honored as a symbol of a lifelong, loving couple. Chinese weddings often feature a Mandarin duck pair in some way.

That was quite a sight. But on another occasion, we saw a Hoopoe, three actually. Walking along the filthy channelized river that runs through downtown, after a very nice lunch with Ma (my travel agent) and his wife Yanni, I noticed a Hoopoe flying back and forth across the river, on our left, to a grassy patch, on our right. Then I saw that there were two of them, and they were feeding a chick in a crack in the stone wall of the river on the far side. The Hoopoe is a bird remarkable for its odd and delightful appearance and behavior, its beauty, and its formidable distribution. It is about the size of a dove. The color of its shoulders and head is a warm beige, surmounted by a dramatic, collapsible-fan crest. The wings and tail are striped black and white. It also has an interesting thin, crescent-shaped bill. The Hoopoe is seen frequently bobbing up and down, probing the ground for worms and larvae. This reminds me of one of those eternally-pumping oil wells.

The Hoopoe is found from very southern England straight across all of Europe, central and southern Asia, and China. It is not particularly numerous in any of these places, however, so far as I know; so, seeing one is special, like seeing a cuckoo. I particularly like the Hoopoe also because of the place I first saw one: the grounds of our hotel in the zona Archeologica at Paestum, one the best preserved Greek temple sites in Italy. Here was this fascinating, ancient bird in this fascinating ancient place. To see one now in Old Cathay was delicious, like running into an old friend half way across the world. I had also seen one right in the middle of its vast range, in Tashkent, several years before this.

* * *

In Kunming, development continues apace. The street at the center of my little world, half way between my apartment and my office, home to the restaurants I frequent, has been completely remade in the last two years. Most recently, there are twenty new buildings – stores, two stories each, alternately painted yellow and dark brown. This replaces a long wall and a string of small one-room shops open to the air. That sort of shop is now completely out of fashion in Kunming. Partly for general reasons, and partly because a conference of nine neighboring provincial governors will be held in June, these are being torn down throughout the city and replaced by newly planted green space or Hong Kong-Shanghai style stores with floor-to-ceiling plate glass windows and doors (much lower prices, though).

More important is what might be called education development. While I was away, an area of hutongs which I used to walk through on the way to and from my office was demolished. I call them “hutongs,” though “hutong-like alleys and buildings” would probably be more correct. They were old one-story red brick buildings, each surrounded by walls and each containing some sort of interior courtyard. They were certainly not from the Ming dynasty: they seemed to me to be closer to fifty years old than to five hundred years old, despite their disrepair. They were quite run down, but this seemed to be more due to the fact that everyone knew they were going to be torn down (and so spent nothing on upkeep) than from centuries of wear and tear. Indeed, when we first arrived in 2002, I was told that they would be torn down very soon, but in fact they survived for three more years. I would say they occupied an area of about half a square city block, taking Manhattan blocks as a sort of world standard measure.

There were narrow lanes or alleys between the buildings. I remember walking through those lanes one night in the pitch dark when I was startled to realize there was something in the lane just in front of me. I used the weak light of the display on my mobile phone to shine on what was there – to discover a young couple necking on the steps of a gate. On another occasion, I saw a Hoopoe in the morning on the narrow walkway ahead of me. The whole complex served as faculty/staff housing in the old days, but the university has built a number of new and much larger complexes in various parts of the city.

In the space which has been cleared, a gigantic middle school, seven stories tall, is rising. As usual, the work proceeds seven days a week, dawn till nearly midnight. Four times as many young people go to college in China today compared with just eight years ago. If this new school is any indication, that number will quadruple again in another eight years. It is not the only new school I see. If I take another route to the office, I pass a brand new six or seven story elementary school building that occupies a walled-off corner of the main campus of the university. Still another route takes me past yet another such school.

And the university itself, as I have previously mentioned, is building – has built – a brand new undergraduate campus on a site far away from the center city. Next year all of the first three of the undergraduate class years -- freshman, sophomore, junior -- will be living and learning there. Seniors will still live on the old campus, nearer the professors for whom they will write a senior paper, one of the major features of the final year of their undergraduate education.

* * *

To continue with The Ring of the Nibelungen for a moment, which I mentioned last time because I had found DVDs of the entire Ring Cycle here -- however odd this may sound in a report from China.

At the beginning of the first opera in the Cycle, Das Rheingold, in the depths of the Rhine, three Rhine maidens swim around (in some productions) guarding the Rhinegold. A fissure opens in the earth and the dwarf Alberich enters, spies the three and lusts. They, however, taunt him and humiliate him for his ugliness. Alberich steals their gold, learning that who renounces love will gain the ability to forge from the gold a magic ring. He disappears with the gold, takes it to the Nibelungen cave, and forges the Ring.

When he takes it to the underworld, the music shifts from Rheinisch to the sound of a multitude of Nibelungen pounding away with hammer and pick.

That is exactly – exactly! -- the sound I hear now outside my window, and just as musical. The reason the sound here is so musical, more of a tink than a thunk, is that the hammers are hitting hard tiles – they are removing the tiles with which all Chinese buildings for at least the past twenty-five years are covered (often inside as well as outside).

When I was here in the spring, the racket out my window was that of the construction of the vast middle school that I see now. I would guess this school has somewhere between five and ten thousand students, all in uniform. Now an old school, which stands behind the new one, and next to the railway tracks, is either being demolished or skinned alive for renovation. There are no large tractors or other earth-moving machines as there would be in the US, not yet. Instead, an army of Nibelungen (in hard hats – and taller, particularly these days) swarm over the buildings pounding away with hammer and pick, using what Fairbank continually refers to in his book as “muscle power.”

And what is this music I am listening to? I am listening to China forge a magic ring of --development. Down the old, up the new. Whether China has also renounced love, I leave to you.

This is China developing itself, at the furious pace known throughout the world. All this takes place after, of course (it’s one of the main reasons the world is so interested in this phenomenon) a couple of hundred years of – what? Turmoil? Catastrophe? Imperial implosion? Revolution? All of the above?

And it is right here, right outside my window. Next time you are in Alberich’s cave, think of China.

End of first half of this chapter. Second half forthcoming. See Additional postings

Chapters are sometimes supplemented by notes. Click Random Footnotes to see.

Table of Contents

Home page

Welcome to a journey, riding webbook or ebook. We alternate between roughly chronological "feet on soil" chapters and "nose in books" chapters. The introductory web posting

of the first two chapters is in full. Click Additional for other postings. The complete ebook, sans ads of course, is available now for purchase:

Click here