Green Lake: Reflections from the Surface of China

8/ Two Warriors

"look like my mother,” he said. "She bore thirteen children in all. Only six boys and two girls lived. The last five children were drowned at birth because we were too poor to feed so many mouths."

Commissioner Lin, sent by the emperor to deal with the opium problem, stood at the very top of Chinese society. Zhu De (Chu Teh) lay at the very bottom. Both are connected to Yunnan province. Lin fell down to Yunnan from the heights of the Forbidden City; Zhu used Yunnan as a stepping stone up to a level higher even than the one Lin had attained. The lowness from which Zhu arose knew no bottom, especially for women, all of whom, as girls, were subjected to the breaking of bones in their feet -- first step (as it were) in foot binding -- and yet still had to work in the field.

His mother, he said, “was so humble that she had no name of her own.” As a girl she had had a name, but after marriage she was known only by her position in the family: as “Mother” to her children, as “Second Daughter-in-law” to her husband’s parents, and as “You” or “Mother of our First-born” to her husband. She was always pregnant, always cooking, washing, sewing, cleaning, or carrying water, and she took her turn in the fields, working like a man.

Ruled first by her father, then by her husband and his parents, even by her eldest son should her husband die (remarriage was forbidden), love was supplanted by ability to work and to provide service. At the same time, it was Zhu’s grandmother, there in Sichuan province near the end of the 19th century, who directed the economic unit that was the family.

She allotted each member his or her task, the heavy field work to the men, the lighter field work and household tasks to the women and children. Each of her four daughters-in-law took their turn, a year at a time, as cook for the entire family, with the younger children as helpers. The other women spun, sewed, washed, cleaned, or worked in the field. . . . My grandmother apportioned not only the work, but she also rationed the food according to age, need, and the work being done. Even in eating we did not know the meaning of individual freedom, and we always left the table hungry. . . . She saw to it that the landlord was paid his annual rent, which was over half the grain crop together with feudal dues such as extra presents – eggs, a chicken here and there, and sometimes a pig.

Grandmother worked, too, "according to her strength until she was laid in her coffin."

The landlord was indeed a liege lord. He moved his family to his cool mountain home in the summer, and tenants were obliged to transport all and sundry – again in the fall. Tenant men were also obliged to assemble as a unit whenever necessary and, weapons being issued, provide him with protection from bandits or uprisings. During New Year and other national festivals or “on special occasions such as when the landlord’s wife or one of his concubines bore another son, or when a banquet was prepared for some visiting official” tenants were obliged to work for the landlord and even to make him special “gifts.”

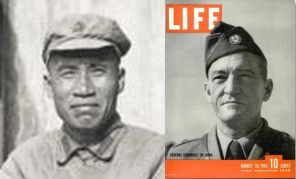

Zhu, the future Marshal of the People’s Liberation Army, is relating all this during the war against Japan, by candlelight in a cave in remote Yenan where the Red Army is holed up, more to protect itself from Chiang Kai-shek than from the Japanese. The person on the other side of the table taking all this down is a remarkable American, Agnes Smedley, suffragette, proponent of birth control, crusader against the British Raj, journalist, writer, square-dancer, left-winger – and one of history’s more interesting spies. Agnes does not speak Chinese, let alone Zhu’s Sichuan dialect, but she does speak German – she started as a spy in Germany (overlapping, in fact, with Zhu there) – and Zhu had spent 1922-26 in Germany, including time at Gottingen University. A translator from Chinese to English is also present as Agnes types away.

Agnes herself was from a hardscrabble background -- raised in impoverished Osgood, MO (population 48) till the age of nine, then in the mining camps of Trinidad, CO. At one point, taking down Zhu’s story, she tells him of her own mother’s life:

We did not work for a feudal landlord, but my mother washed clothing for rich people and worked in their kitchens during holidays. She would sometimes sneak out food for us children, give us each a bite, and tell us of the fine food in the home of her employer. Her hands, too, were almost black from work, and she wore her hair in a knot at the nape of her neck. Her hair was black and disheveled.

Somehow Agnes managed to escape her mother’s fate and travel the world, India and the UK as well as Germany and China. She was involved in the Hindu-German conspiracy during WW1, a scheme by Indian nationalist groups to throw off the yoke of the British Raj. She had a relationship with Richard Sorge, Russia’s top spy, one who warned Stalin (fruitlessly) of a coming German invasion and who informed him that the Japanese were not going to invade the USSR (enabling Stalin to transfer troops, tanks and aircraft to the European theater). Sorge was able to do all this thanks to Agnes having introduced him to Hotsumi Ozaki, a journalist raised in Taipei, a communist, and as of 1938 a member of Prime Minister Konoe’s inner circle. Her cave was right up there with those of Zhu, Mao, and Zhou Enlai.

Zhu was Hakka. “Hakka” means “guest family,” connoting migration within East Asia, and the Hakka constitute a large ethnic group within the Han Chinese, one now centered in South China, particularly Guangdong province. Hakka Chinese is a separate language from both Mandarin and Cantonese. Many important political and military leaders in China have been Hakka, including Sun Yat-sen and Deng Xiaoping as well as Zhu De.

Among the many startling things about Zhu De are that he was able to obtain an education at all and the degree to which he played key roles in the history of China before he met Mao.

His education began with the Old Weaver and tales of the Taiping Rebellion, centering on another Hakka, Shih Ta-Kai (Shi Dakai). During the rebellion, the Old Weaver had served as a foot soldier in the troops commanded by General Shih. Now he is an itinerant who trades stories and weaving for food and shelter. The stories Zhu De hears are of good versus evil, an autochthonous army of peasants seeking to throw off the yoke of Manchu royalty kept in power by the aid of foreign devils. The deep peculiarities of a movement led by a failed imperial examination candidate who decides he is the brother of Jesus play no part. But although the Old Weaver’s stories begin Zhu’s education, it is Hsi Ping-an (Xi Pingan) who is the main influence. Zhu’s extended family decides that since the bane of their existence, tax collectors, officials and unbridled army units, respect men of learning, the family will use money it has been saving to redeem the mortgage on the ancestral home on educating three of the male children instead. This does not go smoothly, however, as the boys are routinely harassed by other students for their lowly status. The family, moreover, is forced to reconfigure the land it rents and the crops it grows (Papaver somniferum is now a necessity), with the result that Zhu goes off with his father’s older brother, who had formally adopted him. It is uncle-father who persuades Old Hsi (not to be confused with the Old Weaver) to take Zhu as a pupil in his home, where he can study with the sons of merchants and, in the case of Zhu’s best friend, the son of a bankrupt scholar.

Old Hsi

loved teaching, he was courageous and enlightened and possessed a sardonic sense of humor that led him to strip ancient or modern heroes of their false trappings . . . he would talk satirically of emperors, generals and officials, remarking that most of them had been rascals who had hired scholars to write tales of their learning or their virtues. The old man urged his students to study so they could travel and study Western learning because, he said, he had heard that science had made Western countries prosperous and strong. He did not know what science was, but he was all for it.

As Zhu’s education proceeded in more traditional subjects, the Four Books and Five Classics of Confucianism, the Twenty-Four Histories of the dynasties 3000 BC through Ming, fears penetrated as deep into China as Sichuan that the Middle Kingdom was being dismantled by foreigners. When Zhu was not yet ten, China was defeated in war by Japan and lost control of Korea. In 1899-1901 another rebellion, the Boxer Rebellion, ended with the Eight-Nation Alliance extracting an immense indemnity from China, with Russia in Manchuria, but also with Japan dominant in East Asia – including ejecting Russia in 1905. Chinese now went to study in Japan, particularly when the imperial examination Zhu was studying for was abolished in September of 1905 in favor of a liberal education and a bachelor’s degree.

Old Hsi kept his students informed of these developments, and also of proposals to convert the imperial system into a constitutional monarchy and still other proposals to do away with it altogether in favor of a republic, whatever that was.

The imperial examination system is dead! Long live the imperial examination system! In fact, nothing had changed, and in the summer of 1906 Zhu and Old Hsi’s son took the first round of the imperial examinations. The first round lasted a month. Hundreds dropped out each week, but Zhu’s name was continually among those eligible for the next phase. In the end he was awarded the status of Hsiu Tsai (xiucai), a licentiate who had passed the opening rounds of the imperial examination.

One of the first things he did then was mislead his family into thinking that he would next take the provincial examinations in Sichuan’s capital. But Zhu did not want to work for the dynasty. He wanted to become a teacher and to earn money to send back to his family. He knew, moreover, that China was changing and that –- remembering Old Hsi -- study of the classics would be replaced by such things as science. His family could never understand that. He had heard of a college, Higher Normal College, in Sichuan’s capital that he could attend; he set out to walk there for the next ten days, arriving in five.

Chengdu was unlike anything he had seen in the past, but the physical environment in which he now found himself was hardly more wondrous than the intellectual environment. Some teachers and some students were joining underground movements aimed at denouncing the proponents of constitutional monarchy as frauds, mainly interested in propping up the old system, and also aimed at doing away with the Qing dynasty entirely and setting up a republic. When the year was over, Zhu joined four other students in setting up a new school in the town where he had received his xiucai. He and his colleagues discovered quickly that the local power structure opposed introducing new ideas about education. Zhu and the others spent much time in court defending themselves from spurious charges –- successfully, showing that the rule of law was not unknown in China. Nonetheless, at the end of this year, he decided that teaching was not “the living road for me,” and to give in to the importuning of a fellow Chengdu student that they go to Kunming and enter the military academy there – a move which his family saw as joining “the scum of the earth.”

The journey south was first by raft and then by hiking over mountains. Smedley is at her best in describing this hike in “a wilderness of snow-clad mountains shot through with jagged black peaks, as if an angry sea had suddenly been turned to stone.” Zhu had heard of

“eating Yunnan bitterness,” but only now did he realize its full meaning. There were villages along the path where the houses were nothing but low, mean hovels where opium-sodden people, with huge goiters hanging from their necks, lived with many goats, sheep, dogs, and an endless variety of vermin. There were small patches of cultivated ground about the hovels, most of the area planted to the opium poppy. The Imperial Anti-Opium Edicts had been proclaimed three years previously, but the major part of Yunnan’s revenue still came from opium, and three quarters of its population smoked the drug.

Zhu is finally admitted to the academy, but only after enlisting as a common foot soldier and going through basic training -- and lying about being from Yunnan rather than Sichuan. Telling them he was from Sichuan initially had led to his rejection, all the more odd because a regiment of soldiers from Sichuan was stationed in Yunnan as a part of the effort to build the new Reform Army (“reform” meaning “capable of doing a better job against foreign devils”). The academy was modeled on those in Japan.

The academy was located not by Green Lake, as I had originally thought and where Zhu lived at one point, but out by what eventually became and served for many years as Kunming’s airport (replaced now by a new, distant one). There were six hours of class each day, including mathematics, geography, history and international affairs, and two hours of drill. One of his teachers was Brigadier General Tsai Ao (Cai E), a man whose importance in Chinese history stands in stark contrast to the attention he has received from historians.

It is here that Zhu De’s own immense role begins, almost two decades before he even met Mao Zedong. Zhu was Tsai’s disciple. Zhu was only four years younger than Tsai, but the latter was a veteran of rebellion and a man of the world besides, one who had studied in Japan, joined the Tongmenghui (TMH), the secret, pro-republican society which Sun Yat-sen had formed there, and been a participant in an aborted anti-Qing rebellion in 1900. No doubt because he was studying with Tsai, Zhu was soon initiated by blood oath into the TMH, a movement peopled not by peasants, but by intellectuals and businessmen as well as soldiers. The Gelaohui was a peasant secret revolutionary society. Here Zhu put his time as a common soldier in basic training to good use, for it enabled him to join this society as well, enduring more blood oaths but putting him in the position of being a bridge between two important players in the overthrow of the Qing dynasty.

He started by convincing the Gelaohui that the railroads being built throughout China were being done so by foreign moneylenders who wanted to prop up the Qing in order to control the Qing. Here I encountered a most interesting paragraph. I have been to the railroad museum in Kunming, a most interesting place. The star of the show there is a model of the narrow-gauge railway that France constructed from Haiphong, the seaport in its Vietnamese colony, to Kunming 1904-10. The emphasis, of course, is on the wonders of the engineering involved and how this aided commerce.

The French railway concession had been wrung from Peking some ten years previously, when the French had staked out Yunnan Province as a part of their sphere of influence. When the last spike was driven, the entire Yunnan Military Academy marched into [Kunming] to watch the first train arrive. Chu Teh stood with the cadets, and when the first train rolled in, one of the academy instructors suddenly wept. Then everyone wept.

Would you not weep if foreign devils now could ride in style into the heart of the motherland?

At this point less and less is what it seems. One of the keys in this, as far as Yunnan is concerned, is that the viceroy firmly believes Tsai Ao to be a constitutional monarchist and totally trustworthy. Consequently, when battles outside Yunnan occur between monarchists and revolutionaries, as they increasingly do, and over a wider and wider area, the viceroy counts on Tsai to prevent them in Yunnan.

Zhu graduated in July 1911, but he and his classmates were not trusted by the prevailing powers and so were given no troops to command. In October an uprising began in Hubei province, in Wuchang (now part of Wuhan). Yunnan’s viceroy battened down the hatches – walls constructed around his residence compound, machine guns mounted, recall of troops of the old army and giving them modern arms. Tsai Ao and the head of the academy (another secret republican) counseled that the viceroy should avoid appearing to be afraid. He should also not execute republicans, as that had set off Wuchang. Instead, maneuvers should proceed as normal, including the issue of ammunition to the Reform troops. The TMH told Zhu to inform the bodyguard unit of an old-army general, in a nearby village, of how events were proceeding. He did. “Later they shot their officers and joined the revolution.”

The TMH had plans for Yunnan. The uprising was scheduled for midnight October 30 but was betrayed by a regimental commander. When the viceroy phoned him at 8, Tsai assured him all was well, though in fact the uprising now began. Zhu managed to rout his own company commander, a monarchist, on the way into the city. Troops cut off their queues. Tsai gave a speech that the TMH had appointed him supreme commander and that Yunnan would now join thirteen other provinces which had declared independence from the monarchy. On the march into the city, Tsai encountered a cavalry regiment sent out to defeat him. A melee ensued, during the course of which Zhu heard firing in the city and realized that the Sichuan regiment, which had been stationed outside the city to the north, had assumed Tsai’s troops were coming in the South Gate. When Tsai’s troops did finally make it to the South Gate, they found it defended by members of the old army who did nothing to prevent entry. Soon, in the center of the city, the viceroy’s new walls were breached, and he was dragged out from under his bed, dressed in the clothes of a coolie. Tsai Ao was now Military Governor of Yunnan.

Next was aid for Sichuan, Yunnan’s neighbor to the north. Tsai marched eight battalions north, but Chengdu and Chongqing revolutionaries succeeded on their own, and by summer 1912 Zhu, now a major, was back at the Military Academy training troops.

The scene now shifts to Yuan Shikai, perhaps China’s most important military leader in the years surrounding the Boxer Rebellion. Earlier, in the contest between the reformist Guangxu Emperor and his aunt, the arch-reactionary Empress Dowager Cixi, Yuan sided with the latter and helped engineer the coup which ended in the emperor’s house arrest (although during the Rebellion itself he disobeyed Cixi’s orders to support the Boxers and attack foreign troops). He commanded the most powerful army in China. After both Cixi and the emperor died in November 1908, the regent, Prince Chun (Puyi’s father), forced Yuan Shikai’s resignation and return to his home village. Now in 1911, with the dynasty falling apart, both major factions wanted him to save them, as did foreign powers. The Wuchang uprising in October portended doom for the Manchus. Calculating that they needed him most, Yuan finally acceded to royalty, on the conditions that Prince Chun resign and that he, Yuan, be made Prime Minister on the 1st of November with a Han Chinese, rather than a Manchu, cabinet.

Yuan resumed command of his army and managed to defeat the revolutionaries at the Battle of Yangxia by December 1, but instead of pressing on to wipe them out he began negotiations with leaders of the new Republic of China, created January 1, 1912 and headed by Sun Yat-sen. Yuan wanted to be President of the Republic. He agreed to force the abdication of six-year-old Puyi, ending three centuries of Manchu-Qing rule and thus consigning the worst of the foreign devils to the dustbin of history. Sun gave way to Yuan. Yuan clearly wanted to be an imperial president, but one of the leading figures in the republican movement, Song Jiaoren, wanted the National Assembly to play the dominant role. When elections were held in February 1913, Song’s Kuomintang (which the TMH had morphed into) won a majority. Yuan had Song assassinated. Yuan next assassinated the Kuomintang, through coercion and bribery. He then struck down all legislative authority: the Republic had merely been a means of bringing down the Manchu. China was accustomed to authoritarian rule. Clearly what China needed now was a new dynasty. And who would be the best candidate to be the new emperor?

Yuan had been aided by a professor at Columbia University, Frank Goodnow, who drafted a “Constitutional Compact” which in effect installed Yuan as dictator, as, said Goodnow, the Chinese were not ready for democracy. Zhu De called this the world’s first fascist constitution. Another factor was Japan’s Twenty-One Demands, including extraterritoriality for Japanese and cession of the seaport of Qingdao, a colony which Japan had wrested from Germany. Yuan agreed to these in exchange for Japan’s support for his ascent to the throne.

In November 1915, a “Representative Assembly” begged Yuan to become emperor; on December 12 he consented. The customary rites were scheduled for January, but before then Yuan’s army was under attack -- and Tsai Ao was perhaps the leading figure in this.

Tsai’s potential as an enemy had been pointed out to Yuan back in 1913. Yuan decided to control Tsai by calling him to Peking and giving him an insignificant office in the new government – where he could be watched. Tsai had no choice and was in Peking for two years, during which Zhu was assigned to the malarial south of Yunnan, fighting bandits armed by the French. Tsai Ao then managed to have Zhu promoted to colonel, for Tsai had escaped from Peking

under the most dramatic circumstances. Evading Yuan’s secret police, who had followed him night and day for two years, he reached Tientsin and took a ship for Japan. After conferring with Kuomintang leaders, he had gone from there to Indo-China and secretly returned to Yunnan by way of the French railway.

Zhu learned of this in December 1915 at a clandestine meeting. Zhu and his troops were ordered to join Tsai in Kunming, swear loyalty to the Republic, call for a rising against Yuan, and march into Sichuan to overthrow his rule there – all this before the coronation set for January 1. Tsai’s forces were to become the Army for the Defense of the Republic (Hu Kuo Chun). When Zhu arrived in Kunming and saw Tsai for the first time in two years, he was “so shocked I could not speak.” Tsai’s body was wasting away from tuberculosis.

But his mind “functioned like a sword, as in the past.” His plan was for the 2nd Division to clean out the neighboring provinces of Guizhou and Guangxi, then proceed to Guangdong, Sun’s stronghold. The 1st Division, led by Tsai himself, was to attack Yuan’s forces in Sichuan. The entire southwest of China would be in republican hands and Yuan would fall. Tsai knew he had little time left on this earth, but he wanted to give it to the Republic.

Fighting began almost at once against four enemy brigades south of the Yangtze. This initial battle, spearheaded by [Zhu’s] 10th Regiment lasted for three days and three nights without pause. The entire Hu Kuo Chun was engaged and [his] troops became famous for their night fighting and hand-to-hand encounters.

On the second day, Tsai gave Zhu two more regiments. By “daybreak of the fourth morning the enemy had been clawed to pieces and the revolutionaries were in enemy headquarters in Nachi.” Nachi possessed a telegraph office that Tsai wanted.

In the reorganization of the army which followed, Tsai raised Zhu to Brigadier General. As the new thrust was beginning, Yuan’s commanders waivered. One, Feng Yuxiang, later the famous “Christian General,” sent word to Tsai that he was not in favor of monarchy. Feng’s superior, commander of all Sichuan forces, clearly wanted to be on the winning side and sent an emissary to Tsai to feel him out. But the war proceeded. By the middle of March south Sichuan “was a battlefield, and for the next forty-five days and forty-five nights the fighting raged without cessation.” Yuan had already tried to gain time and support by postponing his coronation. By the end of March, he abandoned it altogether. To no avail. When two of his top generals, one in Sichuan, the other in Nanjing refused to obey his orders, he went berserk, so Zhu tells Smedley, and “rushed into the room where one of his concubines lay in bed with her newborn baby, and hacked them both to pieces. He was that kind of man.”

By June, Tsai’s forces had defeated Yuan’s. On June 6 Yuan died, of uremia. Throughout, Zhu considered him but an instrument of foreign imperialism, manipulated by foreign bankers who found him a ready and convenient means of controlling what they wanted from China. In Zhu’s opinion the government that replaced him was a government of warlords and imperialist lackeys. Tsai, however, was appointed Governor General of Sichuan. He ordered Zhu to push the enemy out of Luzhou in the province’s southeast, which Zhu’s ragged forces, now part of the Protection Army, succeeded in doing.

Tsai’s health was failing rapidly. He had to be carried into the living quarters connected with Zhu’s headquarters, ordered by his doctors to remain in bed. He did so for two weeks but then had himself transported in a sedan chair, in command of five regiments who fought their way to the capital. Zhu said:

Local militarist armies swarmed everywhere, ruling territory as their private property. Warlordism, sired and fed by foreign money, was Yuan Shi-kai’s legacy to China.

Tsai managed to serve in office only ten days before his health compelled him to leave for treatment in Japan, treatment he knew was futile. Zhu “stood sorrowfully on the pier and watched Tsai Ao’s boat fade into the mists of the Yangtze . . .”

Life bereft of Tsai was dark. Zhu had somehow managed to marry during these events; his wife even produced their son shortly before word came on November 18 that Tsai had died. Shortly thereafter his wife contracted what was thought to be typhoid and died. One of his closest friends then succumbed to tuberculosis. The struggle was far from over, even more complicated now as leaders on both sides proved not to be what they had seemed, and Zhu had an infant son to care for. All this

had a nightmarish quality. His figure seemed to move through a miasma of chaos, at first confident and hopeful, then confused and stumbling until he was finally sucked down into the very militarism which he thought he was fighting.

His only hope for his son was to remarry, which he succeeded in doing, to a very modern woman (she insisted on choosing among offered suitors), with whom Zhu clearly fell in love. This occurred during what is now called the New Culture Movement, roughly 1915-1925, an intellectual revolt against the backward-inward-looking culture of China in favor of democratic and egalitarian ideals oriented to the present and to the future. Perhaps the defining moment in this came two years after Zhu’s remarriage, the May 4th Movement of 1919 protesting China’s treatment at the Paris Peace Conference which followed the Armistice. China expected an end to extraterritoriality and to Japan’s imperialism, including cancellation of the Twenty-One Demands and the return of Qingdao. The April 1919 Treaty of Versailles gave China none of this. Japan was not departing Qingdao and was even awarded the islands in the Pacific that Germany had acquired – significantly for December 7, 1941. On May 4th demonstrations led by students in Beijing broke out and spread to other cities across China in the next few days, fostering crippling strikes, the burning of Japanese goods, and many arrests. The Chinese representatives to Versailles refused to sign the treaty, but the main legacy of the movement was a spur to leftism.

Zhu’s base for the next five years was Luzhou, where he and his wife, and like-minded friends, managed to live rather like western intellectuals of the same age. This happy respite, however, ended again in that miasma of chaos. Far away Beijing was dominated by alternations among the warlords that the Beiyang Army, Yuan’s army, had devolved into. Zhu saw them as lackeys of imperial Japan. Zhu brought his family to Luzhou, now that he was able to support all of them. But this was unwise. It deprived them of the daily farm work they were so used to; they were unhappy. Much worse, he commissioned his two younger brothers and had them join his brigade’s attack on a warlord in eastern Sichuan. This ended not only in defeat, but in the death of his two brothers. His family fell apart, his army suffered more defeats, and he fell into deep depression, even succumbing to the addiction of opium.

Yunnan offers a way out, action to take. Tang Jiyao, Tsai Ao’s colleague and a supporter of Sun Yat-sen, is now military governor of the province. Once in power, he had become more interested in profiting from the opium trade than in democracy in China. He commands only a weak army, however, and Zhu quickly takes over Yunnan. It is during this period that he lives in the residence close to Green Lake. Revisiting Kunming is a bittersweet experience because he is so often reminded of Tsai Ao and of his first wife. It does, however, help him think about his own future and China’s, something which results in his resolve to leave China and go to Europe to study.

Soon after taking over, Sun Yat-sen calls away Zhu’s army from under him: Sun needs it for a campaign against monarchists and warlords. Tang Jiyao then returns. Zhu is forced to leap on his horse and with twenty others ride northwest, with the plan of circling back through Sichuan and then down the Yangtze to Shanghai. The journey is a cliffhanger which might be entitled “The Perils of Poor Zhu.” Zhu and the reader are left hanging after nearly every paragraph. There is, for instance, crossing the river into Sikiang province (now part of Tibet), pursued by a local warlord bent upon pleasing Tang Jiyao. Is the warlord on the far side friend or foe? Will Zhu be able to cure his addiction with the help of a herb from Guangdong? In Sichuan, after visiting his wife and new son, now six, in the village to which he sent them, he is “invited” by Yang Sen, one of the five warlords of Sichuan, to come for a visit. Should he accept? Zhu

wired his acceptance and bade his wife and child farewell. He never saw them again. Thirteen years later they were murdered by the warlords of the west.

Will Zhu escape the lion’s den?

Spoiler alert: Our hero does make it to Berlin, where to his memberships in TMH, Gelaohui and Kuomintang, he adds CCP, in secret and with the help of Zhou Enlai. Before departing Shanghai, he had taken time to explore and to know that city, Beijing, and other areas of which he had only read. (He also transfers $10,000 to a bank account in Paris). In Germany he also wants to explore and to know, buying maps, planning routes, seeing much of what this thing called “the West” is all about. Although he visits art museums, enjoys the music of Beethoven, and goes to the opera, it is in fact a factory making locomotives out of pig iron that impresses him most. At one point he leaves Berlin to study at Gottingen, a university associated with Bismarck, Gauss, Schopenhauer, and Max Born, among others. Smedley says that in his four years in Germany, Zhu learned enough German to carry on a conversation, but not to understand a scholarly lecture. No matter: he isn’t there for a degree, but to learn from the West and to learn about Marxism-Leninism, which he studies assiduously. He also participates in demonstrations, strikes, and underground CCP activities. His account to Smedley includes him being deported from Germany but fails to mention that he then traveled to Moscow for training at the University for the Toilers of the East. He was in fact selected to join a secret military training class there and became head of the group he was in because of his previous training and experience. Much of the instruction is on guerilla warfare.

When he returns to China, he finds a country ruled by even more warlords than when he had left, so many it is hard to comprehend, grouped into the following cliques:

Northern Southern

Anqui 7 Yunnan 4

Zhili 4 Guangxi 4 (Old)

Fengtian 10 Guangxi 3 (New)

Shanxi 1 Guangdong 2

Guominjun 4 Kuomintang 6

Shandong 2 Sichuan 5

Ma 9

Xinjiang 4

65 warlords! And there were many lesser ones as well. Of course, these guys were not a gentleman’s club, and they often fought each other: heads were at stake, and sometimes on stakes. Any count is transitory, but the general situation is clear. Back in China, Zhu reports to the CCP’s general secretary, Chen Duxiu, who makes him a member of a military intelligence group –- Chen views Zhu as a valuable connection to the sea of warlords in which he is swimming. The group decides Zhu is particularly suited to contact Yang Sen of Sichuan, who had “invited” Zhu to that meeting years before. This proves a good choice, and Zhu ends up as a useful aide to Yang. Among his services to Yang is to convert him to the Kuomintang.

When Zhu was in Shanghai before leaving for Germany he had met and talked with Sun Yat-sen. Sun wanted him to go back and reorganize the Yunnan army, but Sun said that attempting alliances with this or that warlord was a squirrel cage in which he had already spent too much time. Better to learn of and follow Russian methods since that revolution was succeeding. In fact, Sun concluded an alliance with Russia shortly thereafter, one which brought in Russian operatives. The alliance was concluded in 1923; Sun died in March of 1925. Soon after Zhu returned, Sun’s successor, Chiang Kai-shek, with Communist help resulting from the alliance Sun had concluded, launched the Northern Expedition, whereby a very large military coalition under his command would proceed from Canton and wipe out opposing warlords, especially the dominant Wu Peifu. (A staunch nationalist, Wu refused to ever enter the hated foreign concessions, not even for treatment of an infected tooth, something which ultimately killed him; he also was noted for hanging a portrait of George Washington in his office – no doubt this is why he once graced the cover of Time). At the insistence of the Communists, and with the agreement of the Kuomintang’s central committee, political commissars were to be installed in the headquarters of each army. Chiang increasingly chaffed at this idea. He also began to disagree about strategy, electing to give Shanghai and Nanking priority over Beijing.

Zhu goes to Wuhan, where the Northern Expedition is now headquartered in order to see Chiang and pledge Yang Sen’s army to the cause. Chiang declines to see him, involved in other matters. Zhu seeks out an old friend who is chairman of the Kuomintang’s Political Directorate. This friend tells him that Chiang is out to suppress the powerful Peasant Leagues which have sprung up, with Communist encouragement, in the wake of the Northern Expedition victories. Accepting Yang Sen’s offer, the friend also tells Zhu to take a group of advisers and become the political commissariat to Yang’s army. Upon Zhu’s return to Sichuan, he finds that Yang Sen’s enthusiasm for the Kuomintang does not go so far as to accept this commissariat, nor does he really wish to attack Wu Peifu, who had helped him in the past. Indeed, Zhu is soon warned that Yang is plotting to kill him and the advisers, a warning which precipitates their immediate flight back to Wuhan.

Zhu is next assigned to become director of a military training school in Nanchang established by the Yunnan army. Not quite what he’d hoped for, but he is a good soldier. Along with this new post comes being garrison commander and police commissioner of Nanchang. A further bonus is his appointment to the Nanchang central committee of the Kuomintang.

As for Yang, he eventually allies himself with Chiang and preys on Hubei province: “like a lean and mangy leopard he began killing every peasant who belonged to a Peasant League, every worker who had joined a labor union, and every girl who had bobbed her hair. Peasant heads were displayed on poles before recalcitrant villages, men and women were buried alive in mass graves . . . .” As for Chiang, he rids himself of the old Kuomintang, starts a new one, allies himself with Shanghai bankers and the Green Gang, a criminal organization he admires for being even more anti-Communist than he is and which is more reliable in suppressing strikes and peasant leagues than his own troops. “At the end of three days some five thousand workers, left-wing Kuomintang and Communist Party members and non-party intellectuals had been slaughtered.” This is just the crest of the wave, which soon spreads across the land, anything left of center attacked and maimed, according to Zhu. Warlords take note and begin to join Chiang’s KMT.

By mid-July 1927, the Great Revolution was finished. Leftist revolutionaries, followed by the Russian advisers, were in flight, rivers of blood were flowing, generals were changing sides, and there was chaos and confusion everywhere.

In December, Chiang marries Soong Meiling, sister of Sun Yat-sen’s wife (who denounces Chiang for his anti-worker, anti-peasant war). Chiang is already married and had converted to Jesus, but the Soong family accepts the bigamy because he agrees “to study Christianity.”

Are you starting to feel that China is not like anything you have ever known?

The Communists regroup in a small village in Jiangxi province, and Zhu is one. There he first sees, but does not meet, Mao. The meeting decides that it is time to “launch the agrarian revolution.” Arm the people! For almost a century the Chinese were impressed by one incident in the First Opium War, an otherwise humiliating defeat by the foreign devils. This was the Sanyuanli incident, near Canton, where, according to Chinese accounts still popular today, 10,000 peasants (or more) rose up and attacked a British battalion that had been pillaging the local area. Launching the agrarian revolution is an effort to take this to a higher level.

The revolution is to start with an uprising in Nanchang, Jiangxi’s capital, and Zhu is part of a committee sent to lead it. Together with He Long and Ye Ting, and under the overall command of Zhou Enlai, he would command a veteran unit known as “Ironsides.” Zhu’s role includes diverting the commanders of opposing forces, the non-Communist Kuomintang, which he does by inviting them to a dinner party at the training school and getting them to settle down for a long night of mahjong.

The uprising was to begin at midnight, but word leaks out, the commanders leave, and Zhu has to launch early. By dawn Ironsides has succeeded. “Nanchang now became a sea of revolutionary banners, and tens of thousands of people and soldiers poured out to a vast meeting where a dozen platforms for speakers were erected.” A shuffle in the CCP also occurs. Then the army marches south; Zhu is in personal command of a new division, the 9th. Given shortages in guns and ammunition, though, he is able to muster only about a thousand troops. The 10th was to proceed on a parallel course, but defects. This causes many of Zhu’s own soldiers to, if not defect, abandon the fight. And when his soldiers do finally battle, winning, they do so at the expense of numerous killed or wounded. Diverting to the walled city of Tingchow and a hospital, where British doctors and locals care for the wounded, Zhu could not linger. With Peng Pai, a peasant leader (one with “a taste for blood,” according to a recent biography of Mao) who came up from Guangdong, he hurries his troops on to the Han River, aiming for Swatow on the coast. Passing through territory Peng Pai had worked in, Zhu’s forces meet with enthusiastic receptions everywhere. Many people volunteer to serve. He finds that women are greatly predominant here because their men folk have been forced to find work in the South Seas. At one point, Zhu even sings for Smedley one of the peasant women songs, accompanying himself on a small harmonium she improbably has in her cave.

The plan for Swatow is that Zhu is to guard the rear at an upriver town with three thousand troops while Peng Pai leads the bulk of Ironsides into the port city. In fact Ironsides is “cut to pieces,” but Zhu does not know that and knows only that battle is raging. On the fourth day Zhu’s forces are bombarded from the other side of the river by an army that has arrived from the north. In addition, victorious forces from Swatow come to get him. He fights for a week before ordering a retreat upstream. Peng Pai somehow manages to exit Swatow alive, gather up scattered peasant forces, and even create a short-lived soviet inland. Zhu persuades his troops to head for Hunan province where the peasant movement has strength.

His chief of staff and three hundred others decide to depart the war, and Zhu allows them to do so. The nine hundred who remain now operate in true guerrilla fashion, moving rapidly, preying particularly on landlords for the money and supplies they need. They capture Dayu, center of the tungsten industry and hold on to the area. Two hundred of those who left now return. In addition, five hundred well-armed men who were part of a detachment Mao had led into Hunan after the Nanchang uprising now join them.

A party conference is scheduled for Guiyang, capital of Guangxi province; Zhu heads his forces there. After the conference, he receives a request from Canton to proceed there to help in an uprising. Sight of his troops on the march triggers enough peasant risings that he is soon “engulfed” in a peasant revolution that stretches from southern Hunan into northern Guangdong. He is soon met, however, by a company of officers-in-training from Canton who tell him the uprising there had begun days ago and is already crushed, they having fled.

Returning to Hunan and adjacent provinces, holding and abandoning various cities, one particularly interesting incident occurs. A warlord had sent six companies of conscripted youth from his Training Detachment to fight the bandit Zhu. Zhu decides to convert them, which he does by capturing them and then lecturing them, with the help of fellow officer Chen Yi. Chen is from a scholarly family, and his commitment to the revolution makes a big impression on the youth. The students then begin to tell of their own experiences, including one whose entire family had been wiped out in the struggles against the landlords.

Such meetings, which came to be known as the “Speak Bitterness Meetings,” were typical of the Chinese revolution in the more than two decades that followed before it was victorious.

All but fifteen of the trainees ultimately join the revolutionary army.

Leiyang, in Hunan, was one of the cities taken and where a soviet was set up. In the course of this, Zhu meets and marries a peasant organizer who is a strong speaker and a very modern woman. Zhu was already married, of course, but he knew he would never again see the wife and child he had left behind in Sichuan. Wu Yulan’s family knows of Zhu’s previous marriage, but they are a progressive family. The Kuomintang later capture Wu Yulan and behead her.

As for Leiyang, Zhu razes it. This is not mentioned by Smedley, but in fact Moscow and its acolytes in the CCP were going through a kill-kill-kill, burn-burn-burn phase as a strategy for leaving peasants with no options other than to join communist forces. The strategy backfired in some areas, with the peasants killing the communists who had come to order them to kill and burn. But Zhu is a good party man, and if the party wants Leiyang razed, so be it.

By April 1928 the Guangxi warlords have organized five divisions to purge Hunan of its revolutionaries. Zhu had at that point ten thousand men, but now has lost many of them in battle after battle. It is decided at this point that he should withdraw to the mountain stronghold which Mao has established in the Jinggang Mountains of Jiangxi. It is now that he first meets Mao.

What is interesting about the Zhu-Mao meeting is that at the point at which it occurs, Zhu has been deeply involved in so much of the history of modern China and Mao so little. This disproportion soon began to diminish and eventually to reverse – and it certainly took Zhu farther and farther from his early years in Yunnan province. But in 1928 it is Zhu who is the warrior who has been involved in the killing of countless numbers and whose life tells of China’s violent transmogrification.

Coda

What one stumbles upon! -- a connection between Zhu and Marilyn Monroe? In this case the stumble was caused by a Leaf on the path. Of course, this has no significance, but it is so odd it might be worth mentioning. Zhu De might find it amusing. The web offered up a 1938 photo of Zhu's wife, standing next to Mao's wife, both in padded uniforms. Who had taken it? An American named Earl Leaf, born in Seattle, 1905. No account I'd read 0f Zhu at the end of the Long March, holed up in Yenan for the duration of WW2, waiting for the war against Chiang, mentioned Earl Leaf, who also, of course, took a Mao-Zhu pic. There's another of Leaf sitting at a table between Mao and Zhu De, Mao's wife on the far right. Turns out he was sent by UPI's predecessor to cover early days of the Sino-Japanese War. But no Leaf photos of the civil war exist. No, he turned his attentions to Marilyn and to Elvis, for which he's more famous. No Wikipedia entry for him. That's hard to understand: "For years, he shot rolls of scantily clad women in his hidden bamboo-covered shack. Previously, the trend in Hollywood had been posing movie starlets in benign domestic settings."

* * *

![]() ot long after Zhu De was born in a remote part of China, Claire Chennault was born in a remote part of the US. The year was 1890 (sometimes he claimed it was 1893). The place was Commerce, Texas, NE of Dallas, though when he was only a month old his family moved to even more remote NE Louisiana, to the town of Gilbert (current population 561).

ot long after Zhu De was born in a remote part of China, Claire Chennault was born in a remote part of the US. The year was 1890 (sometimes he claimed it was 1893). The place was Commerce, Texas, NE of Dallas, though when he was only a month old his family moved to even more remote NE Louisiana, to the town of Gilbert (current population 561).

Chennault was not Hakka but Huguenot.

My ancestors were Huguenots who left Alsace-Lorraine in 1778 to fight with Lafayette in the Revolutionary War. They settled in southwestern Virginia. Succeeding generations pushed westward through Tennessee and Mississippi to the flood plains of Louisiana. There, in 1842, my grandfather settled to clear three hundred acres of rich bottom land and devote the rest of his life to raising cotton and a large family. [Way of a Fighter, 1949].

There are similarities between Hakka and Huguenot. Both are distinctive ethnic groups with their own language within a much larger population, though that distinctiveness is increasingly confined to their history, particularly in the case of the latter. Both can claim many important figures in the history of their country. In the case of USA Huguenots that would include Paul Revere (Rivoire) and Jack Jouett, the “Paul Revere of the South.” Jouett, in June 1781, was awakened from his sleep on the lawn of the tavern at Cuckoo, Virginia by British cavalry of the infamous Banastre Tarleton attempting a surprise capture of Jefferson and the Virginia legislature. Jouett rode through the night with a warning that saved the day. E.I. du Pont is another famous person descended from Huguenot stock. Even Warren Buffett, FDR, and Winston Churchill can claim some Huguenot genes.

Zhu De’s mother did nothing but bear children. Chennault’s mother was not nearly so insignificant, but she died when he was five.

When I was ten, my father married again. His bride was Lottie Barnes, my teacher in the Gilbert grade school. His choice of a wife could not have been better, for I had already learned to love her. Reared on a farm near Calhoun, Louisiana, she too loved nature. Before her marriage to my father, we had had many horseback rides, walks, and picnics together. She encouraged me to live the life I loved so well. She also encouraged me to be ambitious. It was not sufficient for her that I be acknowledged the best hunter, fisherman, and athlete among the boys of my own age. She also demanded that I lead in scholastic standing. Until her sudden death five years after her marriage to my father, she was my best and almost only companion. After her death, which I was fifteen, I was alone again and really never found another companion whom I could so completely admire, respect, and love.

Zhu De’s remarkable education reflected a system which had begun more than a thousand years earlier; Claire Chennault’s education reflected the modern idea of a college education. Chennault attended Louisiana State University, which had opened only several decades before he was born, and a year before the Civil War. (Interestingly, William Tecumseh Sherman was LSU’s original superintendent, resigning as soon as Louisiana seceded from the Union). Chennault attended LSU for three years, but when he came to focus on teaching as a way of supporting himself, transferred to Louisiana State Normal for his senior year so he could obtain a teaching certificate.

Before this, and about the same time that Zhu entered the Yunnan Military Academy, Chennault had applied to both West Point and the Naval Academy. He in fact traveled to Annapolis in 1909 to take the entrance examinations. He learned that cadets were confined to the grounds of the Academy for the first two years, something which proved to be too much for a young man who had roamed about in the wilderness every day, hunting and fishing. He handed in a blank final paper, telegraphed his father that he’d failed, and scurried back home.

Soon thereafter, however, he found the military he wanted to join:

A rickety old Curtiss pusher biplane, wobbling through the air at the Louisiana State Fair in 1910, first turned my ambitions upward. Like most young men, I was looking for bright new worlds to conquer . . . .

The first powered flight in the history of humanity had occurred only a few years before this, so the sixteen-year-old Chennault was indeed looking at a new world in the making. Less than a year after the state fair, the first powered flight in China took place in China, at a racecourse in Shanghai; plane and pilot were French, however.

After some teaching at places like Athens (the one in Louisiana), where his “principal qualification” was that he was considered a minor and could therefore rough it up with unruly students and not be charged with assault, and also work in Akron, OH making inner tubes to be used for vehicles plying Flanders Fields, the US entered the war in April of 1917. He immediately applied for flight training – turned down because at 26 he was too old. In August he is at an officer’s training school in the Army, graduating in a wonderful ninety days; assigned to a base in San Antonio where Kelly Field had been built; wangles a job as a sort of high-class drill sergeant; rejected by the flight training programs at the Signal Corps – but learns to fly. By the fall of 1918 he is at Mitchell Field on Long Island, preparing to ship out to war. But the Armistice intervenes.

Shortly thereafter he nearly died, not in a crashed plane but from the Spanish Flu at Langley, VA that winter. Stricken soldiers back from the war replaced airplanes in the giant hangars.

I was quarantined in a hangar in charge of 102 patients. There was a steady stream of stretcher-bearers hauling the dying out of one end and bringing fresh cases in the other. Flu hit me hard. I was hauled away one afternoon to a small outbuilding where the dying spent their last hours. The officer next to me died early in the evening. I was barely conscious when a doctor and nurse came in to check him off and a detail carried him away. As they left, the doctor told the nurse to lock the door.She protested, “The other boy isn’t dead yet.”

“He will be before morning,” the doctor answered. “Lock the door.”

Typical of hard-driving, hard-smoking, hard-drinking Chennault, he claims that a friend who left him a bottle of bourbon the next morning was responsible for his recovery. Chennault’s flight training back at Kelly Field is in some sense the equivalent of Zhu’s training in Kunming. The advanced course was in acrobatics, and he “was hooked for flying like a Tensas River bass on a minnow-covered barb.” When he graduated in the spring of 1919, he was not given the rank of brigade commander, but certification as “fighter pilot.”

Then he was mustered out of the Army. After some months as a civilian, he was able to join the newly-commissioned Air Service. This included more training by the First Fighter Group which included WW1 aces. He notes that powered flight may have begun in the US, but France, Germany, and England had taken the lead in producing the best aircraft. He was taught WW1 one-on-one fighter pilot combat in the Texas sky. He compares this to medieval jousting, and enjoyable, but “it seemed all wrong to me.” War is about “massing overwhelming force,” not about individual dogfights.

He is sent to Ford Island in Pearl Harbor, only later the ill-fated Naval base. He sports a huge black mustache “with waxed tips in the best fighter-pilot tradition.”

With a deep tan, fierce mustachio, and white dress uniform, I fancied I cut quite a figure. Later I had to shave the mustache when I became a flying instructor at Brooks Field. It frightened the cadets.

A large mustache and a low tolerance for nonsense. Why just dive away from a fighter pursuing you? How about an Immelmann (up in a half loop, twisting away at the top)? What is the point of towing targets for antiaircraft gunners at a fixed height and speed? How about diving on those gunners and pretending to strafe them? (This caused him to be confined to the post for a week). Wouldn’t it be possible for an entire squadron to perform “a formation Immelmann”? Isn’t the best use of a warning system to give pilots information about the location and speed of incoming aircraft, rather than simply to alert civilians to take cover? Wouldn’t it be good to write this all down in a manual? The manual “won an official commendation and then gathered dust on a Washington shelf.”

Back to Texas. Wouldn’t it be a good idea to experiment with Billy Mitchell’s idea of training paratroopers? Major General Charles P. Summerall, Army chief of staff, didn’t think so (he also testified against the Air Corps at Mitchell’s trial) – but the Russians did. They were willing to quadruple his salary, pay his expenses and give him the rank of colonel, plus the right to fly any plane in the Red Air Force. But Chennault still had hopes for an American air force.

Poor guy. One commander in charge of a major training exercise decided that the best way to defend against an invasion by sea was to pull back and dig trenches, leaving the invading force free to approach. The Air Corps was restricted to bombing the trenches the enemy would surely dig, a tactic “about as effective as bean blowers against an armadillo.” The commander, General Kilbourne, when Chennault criticized him at a hearing, succeeded in having the future Flying Tiger’s name “permanently removed from the list of officers scheduled to go to the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.” Without that school’s imprimatur, Chennault could never advance in the US military.

Chennault’s problems were not only with backward commanders in the Army, but also with forward-looking commanders in the Air Corps. They had fixated on the power of the bomber, a fixation enshrined in a text produced by an Italian General, Guilio Douhet, The War of 194- [try getting that title through a text editor]. This book “painted a brilliant picture of great bomber fleets fighting their way unescorted to targets, with the enemy fighters and flak impotent in the fact of their fury.” Advances in aircraft design assisted the theory, and various unimaginative exercises were devised to demonstrate it, some of which Chennault was forced to take part in. Here he emphasizes how important advance warning – advance information tailored to fighter pilot needs – is. Without it, fighter pilots had much trouble even finding the incoming fleet of bombers. He notes that one exercise designed to omit advance information resulted in the conclusion that fighters should not be built at all; his criticism of this was so severe that two years later a second exercise was conducted where a net of observation posts was permitted, with the result that fighters were able to attack the bombers “on every attempt that was made” – though the “bomber boys set up a deafening clamor, blaming ‘unfair conditions’”. The bomber boys were even opposed to developing long-range escort fighters to protect their fleets, a policy which was not shot down until 1943 “when unescorted B-17 raids on Germany were being chewed to bits by Luftwaffe fighters”.

One of the impressive things about Chennault is that he knew his barnacles, a phrase used about Darwin, though in Chennault’s case it was aerial combat tactics rather than marine invertebrates. He found that the best:

had been developed earlier by the Germans. Oswald von Boelcke, an early German ace, was the real father of fighter tactics. He discovered that two planes could be maneuvered to fight together as a team, and he grasped the tremendous tactical implications of his discovery. . . . Before he was killed in a collision with one of his own pilots in October, 1916, Boelcke taught his theories to young Manfred von Richtofen. During the winter of 1916-17, Richtofen molded his famous Flying Circus out of the new Fokker triplanes and Boelcke’s tactics. . . . Allied airmen never defeated the Circus until after Richtofen was shot down and Herman Goering took command [who then led the Circus back to individual dogfights].

Chennault was deeply interested in fighters as defenders as well as attackers, so much so that he authored a book on the subject, The Role of Defensive Pursuit.

This text defines all of the principles and factors involved in the employment of defensive aircraft – whether single-seater fighters or modern jet- or rocket-propelled missiles. It was never really accepted by the U.S. Army, but it was the basis for the organization and operation of the famous Chinese air-warning net, which gave us a tremendous advantage over the Japanese Air Force in China from 1941 to 1945. A similar net would have saved the U.S. air units in the Philippines in 1941 from their swift annihilation.

“Three Men on a Flying Trapeze” -- that was the name of the acrobatic team Chennault led for three years at this point as way of demonstrating the Army Air Corps’ superiority to the Navy’s Helldivers acrobatic team. His full-time job was fighting the bomber boys, so the acrobatics were a diversion, though they also enabled him to hone some of Boelcke’s theories. He was losing the war, though. The bomber boys ultimately had fighter tactics eliminated from the curriculum of the tactical school. And Chennault’s health began to crumble. He does not mention his cigarette smoking, but he ultimately died of lung cancer (appearing in ads for Camels near the end, as he needed the money to pay his doctors bills), and that no doubt played a part. In hospital in the winter of 1936-7, he began to think of the spring eddies of the Mississippi River.

All my life I have seen boyhood friends caught in the eddies of life and sucked under or whirled aimlessly about in ever narrowing circles – some as river gamblers, dead from gunshot wounds; others struck by yellow fever, which raged unchecked through the swamplands; and others still caught in the drudgery of trying to eke a living from cotton farming in a losing battle against palmetto root, bad weather, fluctuating prices, and the passing years.

Was he now in one of these eddies? Shouldn’t he strike out “for open water and the main current” of his ambitions?

The last of the Trapeze performances had been in Miami in 1936, where one of the spectators was General Mow Pang Tsu of the Chinese Air Force. Ultimately Chennault was asked to recommend people for the flying school being established at Hangchow [Hangzhou]. First among his recommendations were Luke Williamson and Billy MacDonald, his two partners in the Trapeze. They had accepted and were now established in China, writing him letters, letters with interesting Chinese stamps on them.

Chennault decided to join them in China, leaving his already large family in Waterproof, Louisiana and heading west on April 30, 1937. He resigned from the Army with the rank of captain. It was supposed to be for only three months; his task: to assess the fighting capability of the Chinese Air Force. He is to report to the person in charge, Soong May-ling, Madame Chiang Kai-shek.

One of the first things Chennault found was that Jack Jouett had preceded him – not the Jack Jouett who had saved Thomas Jefferson, of course, but a colonel who later became president of the US Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce. Jouett had been invited to establish military flying schools, starting in Hangchow five years previously, though this effort began to bog down when the Americans who staffed the school refused to get involved in one of Chiang Kai-shek’s battles against a rival. Chennault also learned that Mussolini had stepped into the breach, offering a training school at Loyang, as well as advisers and planes – an effort which soon retarded rather than advanced the Chinese Air Force. For one thing, all trainees wanted to graduate, whatever their skill-level, something which the Italians were happy permit.

Chennault is busy at his work in July when the shooting war between China and Japan begins, precipitated by a confrontation in Peking known as The Marco Polo Bridge Incident. Chennault immediately offers his services and is immediately accepted. Having practiced for war, having written about war, now he would taste war.

A number of things immediately demonstrate that this is will be no textbook war, however. There is Jerry Huang, who shepherds him around over the next months. At one point, Jerry tells Chennault and MacDonald that he has found a much better place for them to stay in Nanking, a palace on a hill. After a few days in these luxurious surroundings, Japanese bombers manage to destroy one side of the palace and land another bomb so close that these two American observers are flattened by the blast. Next day Jerry appears at the airfield “bubbling over with a tremendous joke he couldn’t wait to explain,” about how he’d foiled the Japanese attempts to exterminate the Generalissimo.

All day the Generalissimo held forth in the palace on the hill, giving the impression he lived there. All foreign visitors were received in the palace. Japanese spies had faithfully reported its location. However, every night the Generalissimo secretly moved to a small cottage concealed in a pine grove several miles away. We had been living in a well·baited booby trap.

Jerry, incidentally, is a graduate of Columbia University.

The US was not helping. It caved in to a Japanese demand that all Americans return home. The US consul (later ambassador) threatened to send the US sheriff from the American concession in Shanghai to arrest Chennault and to see that he lost his citizenship. Chennault ignored the threat and soldiered on, in a strictly civilian role. “Although on many occasions I directed combat operations of the Chinese Air Force, I never issued an order” – only “suggestions.”

He lists the other problems that suddenly confront him:

pilots who refused to bail out of crippled planes because returning without their plane meant losing face-! couldn't convince them their lives were more important than their face; building runways without engineers or machinery; headquarters that took two days to write air-combat orders, with each copy laboriously hand painted with brush and ink; teaching artillerymen who had never shot a duck to lead a moving target in the air; wrestling with a firing squad for the lives of pilots who bad inadvertently disobeyed orders-the Japanese were killing them fast enough without any help; and blunting the keen edge of my American impatience on the unyielding stone of Chinese imperturbability.

Soon the Japanese had complete dominance of the air over Shanghai and eventually Nanking, Chang Kai-sheks’ capital. Chennault had some success teaching Chinese pilots a novel tactic, dive bombing at night, in hopes this would minimize the chances the pilots would be shot down. A defining moment came when he was standing next to Madame, watching pilots return from such a mission.

She was obviously pleased when all eleven planes were sighted over the field. Flying weather was perfect as they circled to land. Her joy was short-lived. The first pilot overshot and cracked up in a rice paddy. The next ground-looped and burst into flame. The third landed safely, but the fourth smashed into the fire truck speeding toward the burning plane. Five out of eleven planes were wrecked landing and four pilots killed. Madame Chiang burst into tears. "What can we do, what can we do?" she sobbed. 'We buy them the best planes money can buy, spend so much time and money training them, and they are killing themselves before my eyes. What can we do?" She had witnessed a demonstration by some of the Italians' prize pupils from the Loyang 100-percent-graduation school.

Chennault continued trying to help the Chinese Air Force, but eventually it was decided to wipe the Italian lavagna clean and start over with a new training program and American instructors. This is how, in the summer of 1938, Chennault came to Kunming.

When I first came to Kunming, it was a sleepy, backwoods Oriental town with a thin Gallic patina. The French had pushed a meter-gauge railroad up from Indo-China, across the tremendous Yunnan gorges to Kunming, and used the cool, dry, and invigorating climate of the Kunming Plateau as a refuge from the steamy heat of their colony. During the summer Lake Kunming was dotted with their champagne-stocked houseboats. Life in Kunming and its environs had changed little with the passing centuries. Squat brown tribesmen crowned with faded blue turbans carried on the provincial commerce, driving pack-mule caravans loaded with salt, tin, and opium over narrow mountain trails. Creaking, ungreased pony carts rattled and groaned over Kunming's cobbled streets. Water buffalo, cattle, and herds of fat pigs were not uncommon sights between the pepper trees lining the main thoroughfare. Here and there the alien lines of a French villa loomed incongruously out of a welter of sooty tiled roofs and lofty olive-green eucalyptus trees. The shrill peanut whistles of the miniature French locomotives mingled with the singsong of Chinese street vendors and clang of ricksha bells.

“Teaching is a difficult job at best” – doubly so, he found, when the students have been trained solely in the classical texts of their ancient civilization and the instructors are mechanically minded Americans who know nothing of Confucius. The new cadets who kept on coming, however, were more and more children of the war and teachable future aviators. One class had enlisted at the end of 1937and had even supplemented their Kunming training with instruction in the US, first seeing action not until the spring of 1944. Chennault says that “They had waited nearly seven years for their revenge on the Japanese, and when their hour of revenge struck, they took it in full measure.”

Chennault also takes satisfaction in fostering an effective warning network, one designed not simply to alert citizens to take shelter, but to give his fighter pilots information about the location, numbers, and types of planes of incoming enemy flyers. He says that the Yunnan sector of the network was developed “as a dire necessity.”

After the Japanese captured Hainan Island, they used it as a base to mount attacks against Chinese training schools, first at Liuchow and then at Kunming after it became the main flying center. The Yunnan net was the first to use radios in China, principally because normal communications did not exist in this wilderness province. Radio parts were smuggled into China from Hong Kong and assembled in Kunming under direction of John Williams, later communications officer of the A.V.G. and Fourteenth Air Force, and Harry Sutter. . . . Eventually one hundred and sixty-five radios operated in the Yunnan net, some of them in such remote and inaccessible spots that even the rugged mule trains could not reach them, and air supply was their only contact with the outside world.

Eventually also, the Japanese bombed Kunming because the “Japanese had too keen an appreciation of airpower to allow the Chinese to hatch a new air force unmolested.” If the weather was good, as it usual is in Kunming, bombers came almost every day, even though initially the airfield had only training planes.

Enemy bombs killed Chinese cadets in their barracks, demolished my house in Kunming, and slaughtered thousands of civilians in the city. A near miss splattered my office with shrapnel and tile fragments.

The “endless grind of training” continued, however. So did the bombs.

Early in 1939 the Japanese began their tremendous effort to break the back of Chinese resistance by sustained bombing of every major population center in Free China. . . . Bombers from Formosa blasted the coastal ports. Foochow alone took more than fifty raids. Students from the Jap flying schools at Canton practiced bombing on the cities of southeast China that later became the springboard for the American air offensive in China-Liuchow, Nanning, Kweilin, Kienow, and Kanchow. Japanese Navy planes from Hainan Island blasted our training fields in Yunnan.

Chiang had moved his capital further west to Chungking, in Szechuan province. The bombers soon reached there also, with devastating results. The Generalissimo tells Chennault to come see him.

The Generalissimo explained that he had a plan for ending the Japanese bombings -- buy the latest American fighters and hire American pilots to fly them. What did I think.

The Gitmo brushes aside Chennault’s qualms (which included doubts about the liquid-cooled engine of the P-40, which would become his primary weapon) and orders Chennault to depart. That order was the beginning of the Flying Tigers.

Within days he is in DC, dining at the home of Madame’s brother, T.V. Soong who has been charged with securing American aid. The best account of this dinner is in Joe Alsop’s memoirs. Joe was then a journalist working for the New York Herald Tribune, but he later came to Kunming as Chennault’s aide.

Chennault presents a plan to T.V. in January 1941. While he is waiting, it becomes clearer and more certain that the Japanese are planning conquest in Malaya, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies, where the oil they need is located (that from the US having been cut off). They had already invaded Vichy French Indochina and occupied Tonkin as a means of preventing supplies to China landing in that port and being transported up to Kunming and Chungking.

The plan involves bombing the areas where the Japanese were staging their further assaults, bombing the Japanese home islands with fire bombs, and forming a fighter-pilot group out of American military personnel who would resign their commissions and come to China to be employed by the First American Volunteer Group. Only the AVG part of this plan was put into action, and the AVG needed planes.

By flying to Buffalo, where P-40's were being assembled for the British by Curtiss-Wright Corporation as rapidly as resources permitted, Chennault was able to work out a deal whereby the Brits would waive their priority on one hundred P-40B’s just coming off the assembly line in exchange for increased production of a newer model. The P-40B was not what he wanted, but it was take it or leave it, and Chennault took it, although the planes had British-caliber machine guns and no radios (they were to be installed in Britain). Moreover, the “The P-40B was not equipped with a gunsight, bomb racks or provisions for attaching auxiliary fuel tanks to the wings or belly.” In February the planes were on the docks of New York city waiting to be shipped to Rangoon; but not until April were they loaded onto a slow Norwegian freighter -– “The first plane was lost when a cargo sling broke, depositing a P-40 fuselage in the waters of New York harbor.”

Men to fly the planes were not easy to come by. The best candidates, of course, were those with military training. “The military were violently opposed to the whole idea of American volunteers in China.” Both the Army and the Navy were planning expansion programs, and they viewed an American Volunteers Group as a threat to expansion. The only option was to go over their heads.

It took direct personal intervention from President Roosevelt to pry the pilots and ground crews from the Army and Navy. On April 15, 1941, an unpublicized executive order went out under his signature, authorizing reserve officers and enlisted men to resign from the Army Air Corps, Naval and Marine Air Services for the purpose of joining the American Volunteer Group in China.

Chennault set up a recruiting unit which somehow managed to overcome the difficulties of dealing with airfield commanders. Here is what the recruiters had to offer: “a one-year contract with CAMCO to ‘manufacture, repair, and operate aircraft’ at salaries ranging from $250 to $750 a month. Traveling expenses, thirty days leave with pay, quarters, and $30 additional for rations were specified.” CAMCO was a business that Curtiss-Wright’s representative in China had set up to manufacture and service airplanes; it was being used here as a blind to maintain secrecy about what the volunteers would actually be doing. In addition, Chiang Kai-shek would pay a bonus for each enemy plane destroyed.

The first group was hired and shipped out by early July.

I left San Francisco on July 8 aboard a Pan American Airways Clipper with Owen Lattimore, special political adviser to the Generalissimo, as a traveling companion. Just before we left, I received confirmation of presidential approval for the second American Volunteer Group of bombers with a schedule of one hundred pilots and 181 gunners and radiomen to arrive in China by November 1941 and an equal number to follow in January 1942.

Rains arrive in Yunnan with the summer, so the original plan to train everyone there had now to be abandoned – the airfields all had rain-soaked grass runways. The Royal Air Force had an airfield in the jungle in Burma with a paved runway, and this was lent to the AVG, though the politics were dicey because Britain did not want to do anything that would induce the Japanese to attack and take its colony away.

Toungoo was a shocking contrast to a peacetime Army or Navy post in the United States. The runway was surrounded by quagmire and pestilential jungle. Matted masses of rotting vegetation carpeted the jungle and filled the air with a sour, sickening smell. Torrential monsoon rains and thunderstorms alternated with torrid heat to give the atmosphere the texture of a Turkish bath. Dampness and green mold penetrated everywhere. The food, provided by a Burmese mess contractor, was terrible, and one of the principal causes of group griping.

Nonetheless:

Every pilot who arrived before September 15 got seventy-two hours of lectures in addition to sixty hours of specialized flying. I gave the pilots a lesson in the geography of Asia that they all needed badly, told them something of the war in China, and how the Chinese air-raid warning net worked. I taught them all I knew about the Japanese. Day after day there were lectures from my notebooks, filled during the previous four years of combat. All of the bitter experience from Nanking to Chungking was poured out in those lectures. Captured Japanese flying and staff manuals, translated into English by the Chinese, served as textbooks.

Chennault had had a narrow profile of the sort of flyers he wanted, but the motley crew he actually got was quite different. They were all sure of their flying proficiency, however – until those seventy-two hours demonstrated to them that they had much to learn.

Our training program went on long after combat began. As late as March 1942, after the group had been fighting for nearly four months, we still had eighteen pilots classified as not ready for combat. No matter how pressing the immediate needs of combat I refused to throw a pilot into the fray until I was personally satisfied that he was properly trained. That is probably one of the main reasons Japanese pilots were able to kill only four A.V.G. pilots in six months of air combat.

One of Chennault principal tactical lessons involved shooting and then diving away. The dogfight mentality of the WW1 that still prevailed viewed this as treason. In the RAF you could be court-martialed for diving away, executed in the Chinese Air Force for diving away. In the battles over Rangoon, however, the RAF and the AVG fought side by side in comparable numbers. “The R.A.F. barely broke even against the Japanese, while the Americans rolled up a 15 to 1 score.” The AVG had been able to polish the lessons Chennault because every pilot had gone through sixty hours of specialized flying.

The autumn of 1941 brought continuing indications of Japanese attacks on Malaya, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies – and Burma. Then came Pearl Harbor.

My worst fears in thirty years of flying and nearly a decade of combat came during the first weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor over the possibility of getting caught on the ground by a Japanese air assault on the A.V.G. at Toungoo. This fear had been gnawing at me ever since mid-October when the volunteer group began to take shape as a combat unit and I ordered the first aerial reconnaissance over the Japanese-built airfields in Thailand.

The chief air officer in the RAF in Burma, however, an Australian, had no such fears and persisted in ignoring Chennault’s suggestion for a better warning network, even barring Chennault from his fighter control room and preventing him from becoming familiar with facilities that were supposed to be used jointly in defense of Rangoon.