Green Lake: Reflections from the Surface of China

18/ Belden and the Revolution

e moved fast, strung over a distance of seventy-five yards; Siatze was walking in front of me now, his back bent slightly forward, his towel acting as a marker for me, like a tail light on the car ahead of you. But the night was not black, though there was no moon and a thin mist. From the sky came a faint light from the stars that made the air fuzzy. Through this fuzziness, on either side of us, came another light, flaring gleams as of burning fires or distant cities, and I saw all the men looking toward them and pointing them out to one another. . . . Somewhere directly ahead a dog barked. Kang ceased talking and quietly cursed the dog. It was the first dog I had knowledge of in many days. The mountain people had killed them all in the Japanese war so the guerrillas could operate. Perhaps this was a Kuomintang dog. . . . We dropped down to a rocky brook bed, and the first two columns continued straight ahead, but ours turned to the right with Siatze in the lead. We crossed the rocks, came out on another path . . . and feeling I was in my twenties again and seeing my first battle, we dropped down the curving slope to a point where the path leveled out beside a mud house. Now Kang halted by a willow tree before the house and he took Siatze's wrist and whispered so low I could hardly hear him, 'Is this the house?'

Jack Belden, American war correspondent supreme, is on a mission to murder -- murder a landlord.

It is 1947 China and Belden has embedded himself in a small guerilla force that is murdering the man not just because he is a landlord, but because he killed Siatze's entire family

‘He shot my wife, my brother and my baby. . . . He buried alive four members of my family. My son, my uncle, my nephew and one married daughter who had come for a visit. One boy -- he was six years -- got away. They bayoneted him, but the knife slid along his forehead and he didn't die.’

Belden joins the mission but has refused the offer of a gun to defend himself should they be attacked by the Kuomintang troops holed up in pillboxes outside this village they are supposed to be defending. Kang, the one who ultimately dispatches the landlord, looks upon Belden's refusal with contempt. So does Belden.

‘You are a bastard, Jack Belden, I thought. Holding on to your neutrality so that you can truthfully say you are an observer if you are caught. But what of the others who are to protect you? It will be a firing wall or a pit for them.'

The guerilla force is led by the Field Mouse, Tang by name. In that lies a terrific story. But then this book of Belden’s about China’s civil war is chockablock -- absolutely

chockablock -- with stories, all of them absorbing, particularly the ones about women. Belden is a reporter; he gathers stories. He better than anybody gets in the middle of things to see

from the inside.

And when he says, 'feeling I was in my twenties again and seeing my first battle," it needs to be pointed out that here he is 37 and that he has seen a lot of battles, maybe more

than anyone else alive. His footing in the rocky brook bed is a little unsure because in 1943 his leg was shattered by machine-gun fire during the Salerno invasion. He somehow returned

to Europe after the doctors and the medicine and covered the invasion of France and the rest of the war to defeat Hitler. His career began in the late 30's in China, covering the war against

the Japanese, about which he wrote a book that Peter Rand, author of China Hands calls “a truly stunning book about the loss of Burma, Retreat with Stilwell, a work now forgotten, but a

masterpiece never forgotten once read.” Now he is back in China covering the civil war in the late 40’s.

This story about the murder mission, told in the wonderfully titled China Shakes the World, despite its drama and its insight, its verisimilitude -- its attractiveness to every

newspaper editor in America with a cigar stub stuck in the corner of his mouth -- was not easy to get into print. A recurrent theme in Belden's book, one just as prominent in those by fellow

China Hands, Peck and White, is how the Kuomintang would not permit any reporting that was critical of its efforts or of -- God forbid! – Chiang Kai-shek. In order to get anything like this out

it was necessary to use subterfuge. But even if you could get something out, the American stake in Chiang and his Methodism was so great that inconvenient truths were actively

discouraged or even suppressed by media moguls, of whom the most prominent was Henry Luce, one-time employer of both Belden and White and graduate of Peck’s own university. That

it was the McCarran-McCarthy America of the late forties, early fifties did not encourage the appearance of “Murder Mission” either. But it did appear, between the covers of a masterpiece,

a masterpiece that after his advance earned Belden, according to Rand, US$28.07.

They find the landlord in bed. He has been sick for two weeks, his women say. They drag him out and shoot him, the whole sequence ably described by Belden -- not

only what happens, but his own emotions at seeing with his own eyes even a villain receive rough justice. Belden is particularly affected by the man’s wife: “The sight of the woman, sitting

on the hill under the stars, with the head of her terrified husband in her lap, moved me. I knew most Chinese farm women were highly emotional . . . when something untoward upset their

daily existence. But this woman had neither cried, complained nor shown any other feeling than sympathy for her husband. I wanted to ask Siatze what he thought of this woman, but I felt

guilty about my sympathy.”

After the landlord is shot in the head, the woman is placed at the front of their retreating column, but her slow bare-footed pace holds up the militiamen. Belden walks to the front and takes

her hand, tugging her a bit, to which she responds.

We were walking across the rolling country now and I felt the rise and fall of the path under my boots, felt the woman’s quick and stumbling steps behind me, felt her hand

tighten against mine and her fingers seeking mine. From the palm of her hand against mine, there came something so intensified, so demanding that it seemed a current moved up my arm

and filled my whole body with a desire to comfort her. She drew closer to me, then said something in a low voice that I could not understand. I looked down at her, trying to catch her words.

Her face turned up to mine. It was so dark I could distinguish nothing of her features: whether she was ugly or pretty, old or young. She could not tell I was a foreigner. To each other, we

were faceless beings in the dark -- nameless, without country and without politics. . . .

We went toward the west and the sky grew paler behind us. As we came through the narrow valley and across the rocks to the village from which we had jumped off, it was growing

light. I pressed the woman’s hand once, released her and turned to look at her. She was young and pretty and she was smiling at me. If she was startled to see a foreigner, she gave no

sign.

The Field Mouse comes up with some shoes for the woman. He asks her how she feels about their executing her husband. Belden says the question was so “sudden and brutal” that it made him flinch, but the woman laughed: “He was an evil man. He always beat me.”

* * *

The used copy of China Shakes the World that I bought through alibris.com, a library castoff, is unmarked, except for one underlining at the beginning of “Part X: The Revolt

of Women.”

I discovered that the Communists’ drive for power was touched at almost every point by women, by their feelings, by their relationships to men, by their social status, by their

symbol as an object of property, religion and sex.

What a remarkable statement! What an insight! If this same point has been made by others since, and frankly in all my reading about the Mao-Chiang contest, about Communism in China, I do

not recall encountering it, it seems certain that the first person to have this insight was Belden.

This comes immediately after the chapter on the murder mission and at the beginning of the story of Gold Flower. When Belden wants to make a large point, he finds a story to

prepare the way for him. “I am condensing her words but nevertheless I shall tell her story at some length because I think it reveals more clearly than a dozen speeches by Mao Tze-tung

just what are some of the techniques of the Chinese Communist party and why they were able to win so many people to their cause.”

He is back on the North China Plain, stuck in the village of Lichiachuang because the Kuomintang has flooded the area by breaking open the Grand Canal in order to stop the

advance of Communist troops. He decides to spend the time trying to find a peasant woman who will tell him her story. He finds Gold Flower, whose condensed story occupies over thirty

pages.

In the middle of Japanese invasion, in a primitive village ten miles from Lichiachuang, she fell in love with her brother’s school classmate, Lipao, who had “a queer voice that had

the ring of an old bell.” That voice was very different from the coarse tones to which she was accustomed; it was his voice that “got under her reserve.”

As she heard Lipao talking, his eyes earnest with youthful enthusiasm, his whole body bent forward intent on what he was saying, talking of such grand and, to her, unheard of things as freedom, democracy and the future of China, her heart yearned over him. He was so noble! . . .

He soon became aware of her interest, and once, when her brother left the room for a moment, he leaned over close to Gold Flower and said: ‘I have learned something from your eyes. I know your heart.’

There follows the clandestine meeting and confusion about what the meeting is for, ending with her falling at Lipao’s feet and begging him, because she would be betrothed to another man, not to make love to her -- “Be my friend, my elder brother, my lover -- in everything but that be my lover,” she had cried.

The affair then turns to nightly meetings of talk and holding hands. When later her girlfriends meet to sew flowered shoes, they play a game of asking each other what kind of man they would like to marry. She is teased when she names Lipao. But the game ends: ‘How stupid it all is! Our parents arrange everything for us. Like as not we’ll get an ugly husband!’ If only they had been born in England, France or America where women can marry for love. In their hearts, they are all rebels against the ‘black society’ of China, and everyone thinks it all right to have a secret lover.

These conversations gave Gold Flower pleasure, for they clothed her affair with Lipao in a moral garment of which it had hitherto been barren. She even began to revel in

her defiance of society and sought proofs that her adventure was making a better woman of her. Sometimes she would take her small mirror from under her pillow and look happily at her

own face. Never had it seemed more beautiful. ‘I have a lover! a lover!’ she would say . . .

Lipao teaches her to write a few characters, which they use to arrange meetings. She realizes the power of writing, indeed the whole love affair “lifts her horizon.” She makes a beautiful thirteen-button jacket for Lipao, raising her mother’s suspicion. In the autumn of 1942 Gold Flower, at age fifteen, is betrothed to a man named Chang, and Lipao to another girl.

Two days before her wedding Lipao calls to say goodbye; though there are people about the house making wedding arrangements, the two manage to slip off to a moonlit meadow

by the village pond. But even now she cannot give herself to him, despite his pleadings. Her torment is great. She puts her lips against his ear and tells him that she will never again be

able to make a jacket for him and that this is the last time she can talk to him. He tries to comfort her, offering the thought that he, too, is desolate, that he will not give up hope, and that no

matter what happens he will always love her.

Where his pleadings had left her cold, his kindness now warmed her. She was excited by a mournful happiness, and she could no longer bear to listen to anything. She went close to Lipao, straight to his breast, threw her arms around his neck and for the first time -- kissed him. How long she was in his embrace she did not know. But for a moment she forgot everything but to kiss.

Yet when their lips part, “division began at once, society crept back between them.” She kisses him again, but her kisses are full of pain “until her heart swelled up with sorrow and she tore herself away and ran sobbing across the fields.”

The next day, feeling ill, in the rain, she goes to Lipao’s house to give herself to him. But the house is dark and empty, everyone is away. Returning home, she no longer wants to live. Her parents are at the wedding preparations.

Quickly, she went to the kitchen and picked up a rope. Groping in the dark, she made her way to her own room, found a bench and dragged it over, near the door. Climbing on the bench, she threw one end of the rope over a beam above the door,

tied a slip knot in the rope, stuck her head in the noose, kicked the bench away and hanged herself.

Her parents find her moments later, but it takes them and the neighbors two hours of hard work to revive Gold Flower. “I won’t obey your commands,” she shouts at her mother. “You stupid woman. You donkey.” She begins screaming and cursing, thrusting away anyone who approaches. But this and the press of all around her exhausts her and she falls into a deep stupor. When she awakes, she is thrust into the wedding sedan chair which is waiting at the door.

When the sedan chair is set down in the courtyard of her husband’s home, she finds that he is not only old but has the beauty of an ogre. His family handles her like a piece of merchandise. He beats and rapes her.

As was custom, on the ninth day she returns to her own family. Pouring out hate and bitterness on her mother, she comes to realize that the fault is not with her parents but with society itself. She is startled when her mother at one point says, “It is not only you who hates society, but me, too.” Lipao appears, but they can do nothing, and she calls after him, “Work hard, do something for society, forget me.”

For years she endures the beatings of her husband, who treats her like a beast of burden. She dons a mask of meekness, quoting the old proverbs about woman and man. The North China famine strikes. Husband and his family eat millet, but she must subsist on husks and leaves plucked from trees. It gets so bad that her husband leaves for Tientsin, intending to become a merchant. He warns that he will beat her to death if she does not let his father and sister eat first or if she is irregular in her conduct. She replies according to custom, but deep within her a wish for vengeance, blow for blow, has formed.

The 8th Route Army appears. They organize a Women’s Association, because “every woman had the right to equality with men.” Gold Flower is skeptical that this will amount to anything and does not join. But her friend Dark Jade does join, and then comes to see Gold Flower. Induced finally to tell her story, the whole river splashes forth. A few days later Dark Jade appears with three other women and confronts the father-in-law, who tells them to go to hell. Dark Jade then brings fifteen more, carrying clubs and ropes. They catch him up “like a fish in a net” and march him off. “The procession went around a corner. Suddenly Gold Flower stopped short in the middle of the street. So this is what happiness is! she thought.”

The Women’s Association holds a well-attended meeting in the abandoned home of a puppet of the Japanese. A woman cadre from the district speaks eloquently of how the 8th Route Army is out to overturn the feudalism of Chinese society and establish the equality of women to men. Her father-in-law is marched in, and the women threaten to beat him to death. But Dark Jade intervenes, arguing that injustice is not to be countered with injustice. The old man responds that he has done nothing wrong and calls on Gold Flower to support him.

‘I married into your family -- yes!’ she hissed into his face. ‘But there’s been no millet for me to eat. No clothes in the winter. Are these not facts? Do you remember how badly you have treated me in these past five years? Have you forgotten the time my mother was sick and you made me kneel in the courtyard for half a day? In the past I have suffered from you. But I shall never suffer again. I must turn over now. I have all my sisters in back of me and I have the 8th Route Army.’

The crowd rushes forward to spit in the old man’s face. Dark Jade pushes them back, and then asks him whether he is ready to reform. “’I will change.’”

A guarantor pledges to bring the man back if he treats Gold Flower badly again. That night the old man is so ashamed he cannot hold up his head.

Gold Flower becomes one of those who haul others before reform meetings. She becomes the cadre that Belden interviewed at length, day-after-day, no doubt persuading her that the more she told about her life and emotions, the better outsiders would be able to understand why the Communists were driving to victory.

Gold Flower also persuades women to work in the fields, both exercising their new freedom and increasing the food available for troops. Even White Purity, the most beautiful woman in the village, does not want to be kept like a bird in a cage and wants to work. White Purity increases the family income so much that, with a variety of persuasions, she pushes her husband out and off to become a soldier.

But Gold Flower has to settle the score with her husband, Chang, and decides to lure him back. Her letter brings him to the family door twenty days later. But his talk with his father-in-law, which Gold Flower clandestinely overhears, reveals the lay of the land. He is going to beat her to death.

Enter Dark Jade. She walks into the conversation between the two men and tells Chang that this is not the past. She says she is being polite to him now, but be warned. That night there is a confrontation between husband and wife, but though a knife is involved, they both shout themselves to exhaustion and no physical violence is involved. The next morning, however, Gold Flower calls for her friends in the Women’s Association, who drag Chang off and lock him in a room. “Let him starve there for three days, the pig!” says Dark Jade. At the meeting Chang feigns injured innocence, even claiming his wife treated his family badly. But he can only hang his head when pressed for details. Gold Flower is brought in to confront her husband, but her testimony is aborted when his low bow is deemed artificial, and he responds to the women’s angry questions with silence; the “crowd fell on him, howling, knocked him to the ground, then jumped on him with their feet.” Those who cannot get close sink their teeth into his legs. Gold Flower thanks her comrade sisters for helping her get her revenge, to which the reply is: “Don’t be polite . . . This is only justice.”

That night Gold Flower presses her husband about whether he has really reformed. He hasn’t. Women should be kept in the old way. There is no 8th Route in Tientsin. If the poor are poor, so be it. Landlords did not steal property. If he were younger, he would join Chiang Kai-shek’s army and take another wife. Gold Flower lies there wondering whether she should report this. She is exhausted from her struggles. He starts to caress her; she numbly lets him make love to her. But down deep her rage is all the while overcoming her emotional exhaustion, and as she is cooking dinner the next evening it bursts forth. She runs to the Women’s Association. This time it is forty women who descend upon Gold Flower’s home. But her husband has already fled.

Belden questions her about the future and is astonished at her responses. Does she now think that love is bourgeois nonsense? By no means, she wants to marry when her divorce is final. What sort of man? “I want a worker or a farmer, and someone who is not afraid of death.” A teacher? Teachers fear death; they don’t teach that America is helping Chiang Kai-shek. An intellectual? He has “a curl in his mind.” A cadre, then? “No, cadres are loyal to their superiors, but they are just looking for advantages. They do no work.” A farmer is what she wants, one who can lead people to produce. “He should be better educated than me so he could teach me things. For example, he should teach me characters. But if I forget them, he should be patient to teach me again and again.” If his temper is violent, she will help him to overcome it and to turn it to work, to leadership, to arm the people.

I looked at this simple farm girl in amazement. She was crude by Western standards. She wore cotton pants stained with manure from the fields. She could scarcely read, though she was learning from the village school three characters every day. She spit on the floor in no ladylike fashion. She wiped her nose with the back of her hand. She was no glamour girl. But she was a woman.

* * *

Here comes the broader point. It is preceded by a brief outline of the history of women in the Middle Kingdom. Chinese society rested upon its Elders and “their possession of women as material sources of wealth.” The rich had wives and concubines, the poor one wife. Belden paraphrases a missionary who named the seven deadly sins against women in Confucianism, including by depriving women of education leaving their minds “in a state of nature,” selling wives and daughters like cattle, compulsory marriage, and female infanticide. This degrades and debauches not only women, but society as a whole, with the result that in modern times there are sections of Beijing where men rent out their wives in the family home and Shanghai has become a giant whorehouse.

Here is the point. The liberation of women

is part of the inner history of the Chinese civil war, just as it is part of the story of the failure of American policy in China. Chiang Kai-shek, in failing to heed the tortured cries of Chinese womanhood, brought on himself a terrible vengeance and a just retribution. The architects of American intervention in China, by ignoring, even being totally unaware of the needs of Chinese women and the part they played in the civil war, evolved theories about the war and tried to force policies on the American and Chinese people that had little relation to reality.

There is nothing farfetched in these statements. It is impossible to understand war and revolution in China in abstract terms. It is necessary to understand human beings. The fact that the pain, anguish and despair of Chinese womanhood has been transmitted by revolutionary fires into new feelings of joy, pride and hope is a phenomenon of tremendous significance for all the world. The revolt of woman has shaken China to its very depths and may shake the foundations of even this strong country. Yet political commentators ignore these peasant women as if they had no part in the drama now being enacted on the stage of world history.

There is something called the Spirit of the Age, no matter how difficult to define. Of what is this Spirit composed? When does an Age begin and when does it end? No matter. It’s there. And the liberation of women has been at the heart of it for the last several centuries. The Spirit has moved differently in West and East, but the underlying essence is the same. Belden’s point is that the CCP grasped this fact somehow, not only grasped it but converted into a powerful weapon.

* * *

Who is this Jack Belden? It is not easy to find out. Recall, however, the remark made above: “He better than anybody gets in the middle of things to see from the inside.” Testimony to this comes from China Hand: An Autobiography by John Paton Davies, Jr., published posthumously

in 2012.

Jack Belden, young, bright, moody United Press correspondent groused to me about how shabbily UP treated him and then asked what I was being paid as a Vice Consul. I told him something in the neighborhood of $3,500 a year, as I now recall it. Jack flared up, ‘I’m as good as you are.’ So he wired UP that unless it raised his salary to whatever it was that I was paid, he would quit.

Jack quits and moves in with Davies. On the way back from dinner with friends, Davies finds that Jack has disappeared. For days thereafter, Davies checks with police, hospitals, even military intelligence. No Jack. Did he fall into the Yangtze and drown?

Ten more days pass. Jack walks into Davies’ apartment.

He had on impulse gone to the railroad station and boarded a northbound troops train. It delivered him to the front. There for about a week he was caught in a battle and Chinese retreat -- days of swirling confusion and terror. Stilwell was delighted to receive Belden’s account of the engagements and rout.

Seems Stilwell had also made it to the front, despite obstacles created by the Chinese High Command, “ashamed of the condition and performance of its forces”, but he had not made it to the front north of Hankow where Jack has gone. “Jack had brought him eyewitness, participant reports of action, to which the official communiqués bore scarcely any resemblance.” It was after this that Jack accompanied Stilwell on the retreat from Burma.

Another source is Peter Rand’s wonderful book, China Hands, though Belden appears only in chapters devoted to other Hands and not often. Rand’s book is about Rayna Prohme, Harold Isaacs, Edgar and Helen Snow, Teddy White, and Barbara Stephens. Rand’s own father, Christopher, comes into the book too, a war correspondent in China at the same period Belden is writing about.

Rand interviewed a China reporter for the Christian Science Monitor back in the day, Hugh Deane, who provided his recollections of Belden among others. In Chungking, Chiang Kai-shek’s wartime capital, Belden “was known to pull the shades down in his room at the Press Hotel and drink himself into a stupor for days on end. You knew when he was ready to socialize when he raised the blinds.” Another reference to Belden alone in his hotel room comes from Rand’s father. His father wanted to stay on in postwar China “to live the unencumbered life,” holed up for days in his room in Shanghai’s Broadway Mansions, home of the press corps, “as Jack Belden did,” or drifting around China for weeks on end.

Anyone who reads Belden’s deeply thought-out books knows what Belden was doing in those rooms by himself. The alcohol may have lubricated the thought process, but the brain was humming, and the fingers were typing with unbounded energy. Like Graham Peck and Theodore White, he had no use for the typical correspondent who confines himself to the war-time capital, or to Beijing or Shanghai, and files copy based on press handouts from the Kuomintang.

The striking thing, though, is that Belden also avoided going to Mao’s war-time capital, and for much the same reason: Belden wanted to see the civil war at the level of the people among whom it was occurring, not from the heights and the isolation of the caves of Yenan: “that cave village had become a tourist center with every foreign correspondent in China hopping over to have a quick look at Mao Tze-tung and Chu Teh, leaders of the Communist party and army, and I had no desire to get mixed up in that circus, fearing that it might be very hard for me to get in close contact with the people, the war or their revolution.” That is the essence of Jack Belden: get out into the middle of things, no matter how dangerous those things are, and report on what is happening there and from that perspective. Jack Belden is something else.

Although Belden pulled down the shades for extended periods in his room at the Press Hotel, he cannot have been alone all the time. He was in love with Betty Graham, the lone female in the small group of reporters in wartime Chungking. She yearned for Mel Jacoby, who was conquered by a new arrival, Annalee Whitmore, of United China Relief. White said that Belden pursued Betty Graham “through five provinces.” She seems rather like Belden himself in some ways:

She soon left again for the front, but never came back. She traveled with the Eighth Route Army, and accompanied Red Chinese forces into Shantung after the war, dressed in a People’s Liberation Army uniform. She ended up in Peiping, following the Communist takeover, passionately in love with Alan Winnington, a left-wing British writer. When Winnington jilted her, Betty committed suicide.

This also comes from Hugh Deane by way of Peter Rand.

Finally, at last, after much digging, there is a bit of Belden himself on his own life. This appears in the oral history book, China Reporting (1987), by Stephen R. MacKinnon and Oris Friesen. The book comes from a 1982 gathering in Scottsdale, AZ of reporters who had worked in China in the 30s and 40s, a gathering held so that they could share experiences and remember their own. Belden did not attend, that would be too simple. But he did give a short interview afterwards in which we find that when he graduated from Colgate in 1933, the Depression denied him a job, so he went to sea.

I decided to jump ship in Hamburg, Germany, but was talked out of it by a prostitute I met. She said I wouldn’t live long if I stayed there. So I went back and finally wound up in Hong Kong, where I did jump ship on Armistice Day 1933, with a total of ten cents in my pockets.

Needing a place to sleep, he wanders up a hill, climbs over a wall in the dark, and finds “a bit of clear space” to lie down and fall asleep. In the morning, he discovers he is on the edge of an open reservoir.

I was lucky I hadn’t rolled off into it and drowned. I eventually got to Shanghai where I made some money playing jai alai and gambling.

During the next several years I traveled between Shanghai and Peking and began learning the Chinese language. I spent some time working for the Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury and made some extra money by making language cards and teaching Chinese to foreigners. I was in Peking when the Japanese attacked [the Marco Polo Bridge] in 1937.

Not much, but at least it is by the man himself.

* * *

But wait! Further digging reveals that a biography of Belden was self-published in 2011 by Gary G. Yerkey, himself a reporter who met Belden in Paris late in his life

and, indeed, had profiled him briefly in the International Herald Tribune of July 25, 1979. Yerkey decided to take the title of one of Belden’s books, Still Time to Die, and convert it into the

title of this biography: Still Time to Live. The wisdom of that choice can be debated, but the book provides much background and is an absorbing read. There is, moreover, one major and compelling addition here to the story of the life of Jack Belden.

Belden got his right leg shot up at the opening of the Italian campaign, in the middle of things, observing the troops taking Salerno. Somehow these troops were able to get him onto a ship which transported him to a hospital in Oran, Algeria. Yerkey has discovered that a nurse Belden had late in his stay there was one who had joined the Army nursing corps only a few months before she met Belden. This was Beatrice Weber of Oshkosh, WI. Yerkey quotes Belden’s words that she had hair like “golden silk” and eyes “like the Mediterranean” and “her lips were always laughing.” But Yerkey leaves out: “She was just over 20 and shone with good health and the joy of service. What the rest of her was like you can imagine from the nickname I privately gave her: Miss Beautiful Body.” All these quotes, and the following, come from Belden’s March 20, 1944 LIFE article, an article that puts paid to the idea that Betty Graham was the great love of Belden’s life. Belden does not name Beatrice in the article, but Yerkey was able to find her.

Their hospital banter early on included her telling him he was the messiest patient in the ward. A young naval officer visiting Belden then says, “He needs a wife” -- to which she replies: “Oh, he’ll get caught someday.” To which Belden replies: “I wouldn’t consider it getting caught.” She starts to go, and he wants to say something to hold her: “’Would you marry me?’ I blurted out. She looked me up and down in an appraising manner. ‘Sure,’ she said, smiling.”

And there’s more, lots more, right in the LIFE article. The when-is-our-marriage-going-to-be theme becomes part of their routine banter, and at one point, Belden decides to amuse himself and her by writing a letter about their honeymoon -- which is going to be, he decides, near Taormina, specifically a “romantic cliff” from which “Cyclops is said to have thrown his rock at Odysseus.” But as he writes more and more of this letter “a subtle change was taking place within me” -- the letter is no longer for amusement but a serious statement of what he has always wanted for a honeymoon. “That was when I first became frightened.”

Beatrice is frightened, too. She has transferred to the night shift, which makes him want to talk to her even more since the evening hours before lights-out at 9 were “always the gloomiest hours of the day.” The banter one evening starts with her asking him if he has decided on the day for their marriage, to which he replies that although it is the man who usually pursues the woman, given his situation it will have to the other way around. “She forked her fingers over my face” and says, “I’ll start tomorrow,” to which he replies “No, tonight.” She looks down at him “pensively,” then crinkles up her eyes and says, “You frighten me.”

We all know where this is going to go. But hold on. Belden wonders what got into him and dismisses it all as a weakness on his part, “breaking down before a woman’s kindness.”

And then there is Beatrice’s boyfriend. He was observed by Belden’s friend Smitty, having brought her to the hospital the night before in his jeep. But the boyfriend was “badly smashed and scarcely recognizable” in an accident several hours after dropping Beatrice off. When he is brought into the ward his bed is just in back of Belden’s. She now arrives early each evening to sit by her boyfriend’s bed and bathe his bruised face. This plunges Belden into “the deepest kind of melancholy,” and he is “overcome by loneliness.” About this time Belden is removed from traction and encased in a foot-to-chest cast; he somehow manages to climb into a wheelchair and then huddles alone in an out-of-the-way alcove, where he says he wants to sleep for the night. But Beatrice finds him out and asks why he wants to sleep there.

So, it all returns. “I was choking with the beauty and nearness of her and I could not speak. I looked across a gulf of aching hope but could only glare.” The wonder of her overcomes him; he takes and kisses her hand. “Then I laid my cheek against it and caressed it.’

Remember, this is all in an article written for the readers of LIFE magazine by a war correspondent at a crucial time in the war -- the landing at Anzio, invasion of the Marshall Islands, bombing of Montecasino, the Japanese invasion of India.

The next day Belden is transported back to the US for further recovery, after six weeks in Oran (most of them before Beatrice). Thinking of her on his way out, “there was no pain.” But the man beside him in the ambulance sings of his happiness in going back to America. “But I only lay there and thought: I am going away from her.”

Belden had written a private note to Beatrice, his “Sweetness and Light,” which she took back to her room to read (so Beatrice later revealed to Yerkey). “You are my destiny, the center of my life, the girl I have been searching for all my life.” “Without our togetherness neither of us will ever find happiness and we’ll live in loneliness for the rest of our days.”

But it is not to be. Belden, who was ten years Beatrice’s senior, married twice, first in 1945 to a French woman he met when Paris was liberated (divorced in 1954), then in 1962 to a high school teach from Long Island (separated in 1966?). With each he had a son.

In 1988, the year before he died and when he was in ill health, Belden received a telephone call in Paris, where he had lived for decades. He did not recognize the caller, who asked if he could guess who it was. “I made a wild mistaken guess and then in a flash thought back 46 years. ‘Beatrice.’”

‘As she was talking,’ Belden later wrote a friend, ‘she began to stammer and stutter. Start a sentence and stop. ‘I want you, Jack, to know -- I’m going to bat for you.’ Stop. ‘I love you.’

We all know where this is going to go. Beatrice, who herself had been married and divorced and is now 68, receives his letter in which he again calls her Sweetness and Light, tells her she is brave to have called him, and: “Hold my hand.” Beatrice flies to Paris.

Beatrice is religious and had sought to serve God by caring for people, whereas Belden (like his hero Stilwell) found nothing but hypocrisy in organized religion. But somehow this difference does not interfere. It is nurse and patient again because in addition to his lung cancer (lifelong smoker) he has fallen and broken his hip and is on morphine. Beatrice is with him for a month, and when she leaves he dies.

Beatrice is insightful. She sees that the love Belden expressed to her in Oran had simply overwhelmed her. She wrote, moreover: “As I looked at his face on the pillow, his dark hair and eyes, I saw the saddest, loneliest man in the world, so quiet, just looking at me from a depth in his eyes that had no bottom.”

Coda: The internet can be a wondrous thing; it tells that as of 2018 there is a woman living in Oshkosh, WI on Parkway Ave whose name is Beatrice Weber. She is 98 years old.

* * *

It was to Kunming that Belden came after walking out of Burma with Stilwell in the spring of 1942. His task was to report on the Flying Tigers.

In fact, the Flying Tigers (the American Volunteers Group, or AVG) ceased to exist soon after Belden arrived in Kunming. The date chosen in 1942 for AVG’s end was a memorable one, July 4. The AVG's last combat took place that day over Hengyang; they shot down four Japanese Nates with no AVG losses.

Claire Chennault, commander of the Flying Tigers and now commander of the successor 23rd Fighter Group (as a new Brigadier General), was at the airfield outside Chungking on the 4th, and Belden interviewed him there. How does he feel about the Tigers’ disbandment? He feels he’s had “the greatest opportunity an air office of any nation ever had” -- collecting and training the group and the ability to “prove my methods sound.” (Here he refers to fighter plane tactics). The disbandment is regrettable. “Now I only look forward to meeting the enemy.”

Belden was able to participate in an attack on a large Japanese airbase on the Yangtze below the city of Hankow. He was in a bomber piloted by Col. Haynes, whom he’d met three months earlier when the colonel had flown into Burma to evacuate Stilwell -- an offer Stilwell refused, preferring the walkout which made him famous. The raid passed over landscape Belden had retreated over in 1938 with Chinese forces. “It was almost like coming home.” Incendiaries set fire to much that was below, including piers and warehouses. Ack-ack guns and pom-poms on a large Japanese ship on the river -- perhaps a light cruiser or destroyer -- began “throwing everything but the kitchen sink at us,” Gunners on the Haynes plane responded, silencing the ship. Two gunboats were strafed by a low-level attack; the second gunboat had a deck swept clean of men -- they had seen their companion craft attacked and so threw themselves into the water. Another attack Belden witnessed was on the main Japanese base at Canton. He rode in one of the bombers, but the day included combat between the bombers’ fighter escort, led by Charles Sawyer, and Japanese Zeroes and the new I-97. “’I see six go at Sawyer,’ Belden wrote in an article in Time on August 24. ‘He makes a head-on run at the leader, pours in a couple of bursts. The I-97, camouflaged with bright green paint, falls away in smoke. Five others do a quick flip to get on Charlie’s tail, but he dives and pulls rapidly away and then comes up again on the corner of our tails . . . We roared homeward, landing safely . . . ‘”

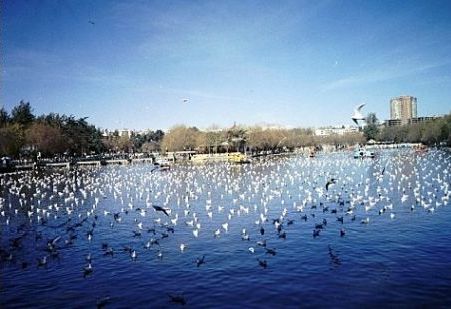

Kunming itself appears in Belden’s book in the chapter near the end which recounts the fall of Chiang Kai-shek and “The End of an Era.” The background for the event recounted by Belden is provided by Jonathan Spence in The Search for Modern China where he describes Chiang’s losing battle with inflation as he was losing battles on the battlefield. Through the end of 1947 and into 1948 “the overall price rise continued at an alarming rate.” A standard sack of rice “sold for 6.7 million yuan in early June 1948 and 63 million yuan in August.” (In 1937, it had cost 12 yuan). In July, the plan was to ditch the old currency and replace it with a “gold yuan,” each of which was bought with 3 million of the old yuan. Restrictions prohibiting wage or price increases were promulgated. But by October, “the failure of the reforms was clear.”

It is within this context that Belden brings us a horrific series of events in Kunming which began in February of the following year and which were precipitated not only by out-of-control inflation but by the fact that there was a significant amount of American currency in Kunming, apparently left over from when American soldiers had been stationed there: “a huge amount of purple-colored Gold Yuan notes of fifty-dollar denomination were brought into the city and used by the Central Bank of China to buy up all foreign notes and gold bullion on the open market.” This immediately caused a doubling of prices. Hard to believe, but on the day after, “the bank announced that all the fifty-dollar notes were counterfeit.”

A riot of thirty thousand people ensued, after a run on the bank shut the bank down. The governor of the province, Lu Han, then arrived in an armored car accompanied by several hundred soldiers. The soldiers “indiscriminately,” as Belden puts it, arrested 118 people and managed to disperse the crowds.

A court-martial, presided over by Lu, was set up on the road opposite the bank building. The arrested men were questioned briefly and then shot to death, one by one, with thousands looking on. The governor ordered the ‘trial’ to come to an end after twenty-one had been executed and after the executioners pleaded that ‘all the rest seemed to be accomplices only.’

* * *

Belden had bad luck with women, and he had equally bad luck with China Shakes the World, published in 1949. The book should have been a best-seller in that he had been the only reporter to get to the front and beyond in the civil war, an event of ultimate importance to America’s foreign policy.

‘I thought my book came out at a good time just when China fell,’ Jack Belden wrote Edgar Snow in 1964. ‘But McCarthyism killed reviews. I believe it was on about page 35 of the Sunday Book Section.’

Belden received a check for $28.07 from Harper and Brothers, after an advance of $1000. He thought of “framing it as a reminder of the folly of writing books. But then I hardly need a tangible reminder.” Belden never published another. He lived in New Jersey and in Paris, where he died in 1989 at the sage of seventy-nine, at the time of the Tiananmen Square massacre. “He was a great drinker, gambler and lover of women who supported his habits, in this country and in Europe, by driving taxis.”

In the early 70’s he returned to China, following Edgar Snow’s advice that he do so on his own dime. Rand writes that reporters traveling with Nixon found him, “in a sorry state,” waiting at the Beijing airport in February 1972: “He didn’t even have a winter overcoat, according to Martin [Pepper Martin of UPI]. Disillusioned with Mao’s China, he was recovering from a host of ailments and working on a book about Lin Piao. In the end, he told Till Durdin that he regretted all the years he had spent on China. He was a literary man, a war writer without a war, who never again found his voice.”

* * *

I have already quoted Belden often and at length, but I cannot leave without an even longer excerpt (found on the internet) because it is so remarkable. Belden may not have published another book, and he may have been driving taxis, but this did not stop him from thinking. The excerpt is not from one of his books, but from a letter he wrote to the Center for Asian Studies which had held the previously mentioned gathering of China reporters in Arizona in 1982, one theme of which was on “advocacy journalism,” citing Belden as an example -- to which he objected!

The trouble with most journalists, reporters, diplomats or otherwise is they have no poetry in their souls. Many historians have acknowledged that Shakespeare's Julius Caesar shows a better and more succinct and powerful understanding of the fall of the Roman Empire than a batch of historic tomes. His Troilus and Cressida might have been written about why the Vietnam war went on. When Nixon sent US troops into Cambodia he said America could not be a 'pitiful giant.' Some four hundred years ago in Measure for Measure, Isabella told Angelo, 'O it is excellent to have a giant's strength, but tyrannous to use it like a giant. . . . Man proud man dressed in little brief authority plays such tricks before high heaven, etc.' And you, dressed in the brief authority of a Center for Asian Studies, presume to tag me (in a bad sense) with the term advocacy journalist. Bah! Give me an ounce of civet to sweeten my imagination.

American journalists are taught objectivity. That's all fine, quote this leader and that leader, etc. But it often leads to a gross error and that is the interplay of the subjective and the objective. 'Look into thy heart and write,' said Sidney. That is what journalists too often do not do or are scared to do. In the time of falling nations what ordinary people feel has an effect on events they do not have in quieter times. Into whose poor people's hearts do you and your war reporters look? As for my own reporting of facts—and I made a distinction between reporting and writing—if you will go to the United States Army, I am sure you will find military maps on the Shanghai war of 1937 there which I objectively gathered and gave to Stilwell. Or if you will look in OSS files. In 1940 I gathered some 50,000 words (facts, not writing) on Japanese and Chinese terror organizations in Shanghai, a great deal from the police. When the Japs captured Shanghai (I was not there) these papers were in a safe. They were thrown in a furnace and burned. Wild Bill Donovan somehow—God knows how—heard about it and one of his agents came to see me in a hospital when I was wounded. I gave them a copy of the material, at least on the Japanese, on Mitsui and Mitsubishi who ran the drug trade and facts on murders. They did not think I was an advocate, they have some sense of my objective facts.

Enough! I have indulged myself in a long-winded diatribe. But I refuse to be hung for what I am not. Since your conference is in some sense on war, I close with a poem by Wordsworth. If, as Henri IV said, Paris is worth a mass, then war is worth a sonnet.

The power of Armies is a visible thing

Formal and circumscribed in time and space;

But who the limits of that power shall trace

Which a brave People into light can bring

Or hide, at will, for freedom combating

By just revenge inflamed? No foot may chase,

No eye can follow, to a fatal place

That power, that spirit, whether on the wing

Like the strong wind, or sleeping like the wind

Within its awful caves. —From year to year

Springs this indigenous produce far and near;

No craft this subtle element can bind,

Rising like water from the soil, to find

In every nook a lip that it may cheer."

Table of Contents

Home page

Welcome to a journey, riding webbook or ebook. We alternate between roughly chronological "feet on soil" chapters and "nose in books" chapters. The introductory web posting

of the first two chapters is in full. Click Additional for other postings. The complete ebook, sans ads of course, is available now for purchase:

Click here