Green Lake: Reflections from the Surface of China

3/ Transformations

![]() n the far side of the lake, after I have made my morning way through the interior walkways, past the people exercising and dancing and exercise-dancing, past the now dying water lilies and out to the perimeter again, I walk through groups of kindergarteners running relay races or jumping up and down to music. Their school across the street has just been repainted in bright colors and looks much better.

A few steps beyond the kids, there is an open stretch of water to my left. Here there is one thing new: the voices of two women coming from inside the park across the broad expanse of water. They are opera singers, of the Chinese opera sort, each warming up her instrument, standing at the edge of the water casting it out as far as it will go.

n the far side of the lake, after I have made my morning way through the interior walkways, past the people exercising and dancing and exercise-dancing, past the now dying water lilies and out to the perimeter again, I walk through groups of kindergarteners running relay races or jumping up and down to music. Their school across the street has just been repainted in bright colors and looks much better.

A few steps beyond the kids, there is an open stretch of water to my left. Here there is one thing new: the voices of two women coming from inside the park across the broad expanse of water. They are opera singers, of the Chinese opera sort, each warming up her instrument, standing at the edge of the water casting it out as far as it will go.

"Wooooooo OOOoooooooe .. OuuuuuuUUUuuuu."

They are not singing words so much as syllables, almost a kind of moaning. They stand under some trees with their backs to an odd structure, which either serves tea or is an administrative office or both -- it looks like a modern ranch house in California, with knotty pine exterior paneling and modern casement windows. I am reminded for some reason of a painting by Edward Hopper, except that the faces are Chinese. I can only hear them for about ten or twenty paces because soon they are drowned out by the boom box used by the fifty or so former chorus girls (so I imagine) who meet every morning in the same place to dancercize. Still, the opera singers are a lovely little interlude.

Nothing much new at the lake, but on the other hand the authorities have just adorned it with a new bumper-cars ride, just inside the entrance gate nearest our apartment. This took over a large round raised platform of stone tiles that was never much used anyway, so it is not too bad, and the kids will love it. Immediately after finishing it, masons built a one-room storage house next to it, which took a couple of days. A week later they tore that down, closed the entrance and began digging up that section of the walkways inside the park. It has been closed for over a month now, and the bumper cars still have not been used.

* * *

The city continues to busy itself with transforming itself. Items:

- There's a new skyscraper abuilding. It is prominent in the view from my apartment window for it towers over everything else, even the tall office buildings. There are many more towering like this in other parts of the city. The skyscraper's upper floors are way above the steeple of the large Christian church nearby which has been under renovation for a couple of years now and which is nearing the finish line.

- Every manhole cover in the city, at least in every part of the city I have experienced, was dug up and replaced last year.

- Last week they replaced the overhead electrical wiring and the transformers throughout the city. I know this because I saw the huge wooden spools of cable they were using, and we had no electricity in the apartment complex for a day; my travel agent, whose office is in another part of the city altogether, told me that they were without power for a day recently also. At about 11 p.m. on Sunday night, I watched as a work crew, standing below a new transformer they had just installed on a platform on one of the utility poles, used a long bamboo pole to reach up and throw the three switches that turn it on. Zzzzz.

- The next day other work crews started digging out some of the manholes again, the ones that lead to valves in water pipes, this time to install new and larger valves.

The universites, too: several have built entirely new campuses, far away from the ones near Green Lake. I don't even know where these campuses are. They will be for undergraduates, and already first and second year undergrads are housed and taught far away. Over the next two years, all undergrads and their professors will migrate, and in our case the Green Lake campus will become a research and graduate teaching campus. (A master's degree used to be a big deal here, sufficient for teaching; now the PhD is required).

The building in which I have my office was completely renovated over the summer, while I was away, and other renovations are in process now. My old office had a certain charm, full of hand-built wooden furniture from (most probably) the fifties, and piled high with papers and paraphernalia left there by a retired professor who hadn't used the office in five years -- everything was removed and disappeared. New electrical outlets and overhead lights were installed; everything (but the concrete floor, which remains the same) was painted white; the rust-stained sink in the corner was magically restored using some sort of acid. Modern office furniture that could populate buildings in Sao Paulo, Milan, Phoenix, or Shanghai was installed.

* * *

Still, the old China persists in the interstices of the modernization process -- now and then. I pay my electric bills at the bank. Banks are open seven days a week. On a recent Sunday, I went to pay my bill. Each clerk sits behind the bulletproof glass and speaks through that round plastic louvered thing that looks like Darth Vader's mouthpiece. Each clerk is fully equipped, surrounded by all the technologically advanced equipment in a modern office: fax/scanning machine, a computer CPU, monitor and keyboard, and a telephone. There is hardly enough room for all this in the little space each clerk occupies. I slip the plastic card identifying my account through the little depression in the marble counter that goes under the bulletproof glass. She checks her computer -- networked to the bank's central computer (often down) -- writes the amount owed on a piece of paper, and I slip two 100 yuan notes through to her. She calculates the change I am owed. She calculates it not on any of all that sophisticated equipment surrounding her, but on an inconspicuous little abacus almost completely hidden from the customer behind the computer keyboard.

And the guy rotating the two balls in his left hand while walking backwards around the lake is still there every day. My expert on these balls turns out to live in Falls Church, VA. Keith emailed me, after I'd talked about them last time:

Chinese "exercise balls," aka "yin yang balls." I've got a bowlful of about a dozen in my living room (I pick up a pair every time I go to San Francisco - it's an ongoing project to fill the bowl). Fundamental and critical difference between Western and Eastern thought: Western thought believes mind is separate from body (Descartes, dualism). Eastern thought believes they are inseparable: the "bodymind." The movement of the balls in the hand works to affect the mind in the same way that acupuncture affects seemingly non-related parts of the body and mind. Has to do with the flow of Qi, the energy of life. ... They're actually hollow, and each one contains a chime that rings when you shake it. It really is a "chime" sound -- very pretty. They're sold in pairs, and one rings on a high note, the other a lower note -- yin and yang. The standard model is the silver steel version, but you can also find balls with very elaborate and colorful enameling, which are probably made more for the tourist trade.

Just walking around still fascinates, perhaps more so now that I see individual faces more clearly and with greater -- delight and amusement. The toddlers are still marvelous, most of them dumbstruck when a Westerner stops to say hello to them, some with the most wonderful little smiles of appreciation.

* * *

In October, on National Day, they had a dinner for three or four hundred people out at the convention center. I was included because the university nominated me as a Foreign Expert. The Governor of the province spoke about the progress that Yunnan is making and the advance of "the reforms." The Governor is the same age as, has the same physical build as, and wears the same spectacles as Hu Jintao, and he of course wears the same dark suits. The entire congregation was then bused over to the basketball pavilion, built in the style of "modern architecture," for a performance by ethnic minorities, singers, dancers, acrobats:

Yunnan Celebration of 55th Anniversary of the Founding of the PRC

Salute to the Five Star Red Flag

Yi People's Style Dragon Dance

Children's Singing and Dancing Light Blessing

Falling in Love with the PRC

My Homeland

Falling in Love with the PRC

Wa People Singing for the New Life

My China Heart

Kunming City Bus Company Drum Dance

Yi People's Cigarette Box Dance and Rap (18 Life-Style Changes of Yunnan)

Opera of Three Different Styles: Flowers over Colorful Yunnan

Female Singer: Zhong Yong Chuoma of Tibet ("56 Blessings")

Cheer for the Homeland in October (Grand Finale)

One of the many things included in the Yi People's Cigarette Box Dance and Rap was a group of guys in Tour de France outfits and helmets making their bicycles dance. They were pretty good.

A few weeks later, Yunnan's annual dinner specifically for those designated Foreign Experts was held. Eleven of us, through the efforts of our host institutions, received gold-colored Friend of Yunnan medals, a handshake from the Vice Governor, and a good dinner. I somehow received the honor of giving a speech on behalf of the recipients. I spoke, one paragraph at a time, each then translated by Aretha Liu, chief translator for the bureau in charge, about my conservation project. (Ms. Liu had a student in the old days who suggested that Aretha would be a good name if Ms. Liu wanted to take an English name, which she did; and incidentally Aretha introduced the Vice-Governor as "Her Highness, the Vice-Governor of Yunnan Province.")

One of the best things about the occasion for me was that Doug Briggs, the young doctor who volunteers his services here through Project Grace, was also honored, and I got to renew my acquaintanceship with him. He is the one from whom came the story about the mountain-top visit to his shoeshine girl's dying mother. He tells me he has lots of other stories he has collected and promises to email them to me; I look forward to getting them. He is moving to the northwestern part of the province, to Zhongdian (recently renamed Shangri-La and close to Tibet), and will be working up there. Since I was sitting next to the Vice Governor at dinner, I asked Doug if he needed anything. He said he needed a certificate from the Health Department that was slow in coming. The Vice Governor is a take-charge lady (what good is power if you never use it?), and soon she was directing another official there to help Doug out.

On my right sat a man from the party secretariat. He spoke good English and had lived in Brisbane for half a year. I explained to him that in America the network of the sort of biodiversity data centers I want to bring to China was built from the bottom up, proceeding state-by-state and eventually surrounding Washington, DC after about twenty years. We hoped to follow the same strategy in China, eventually surrounding Beijing. He said: "you know, that strategy is the same one Mao Zedong employed!"

* * *

Odds and ends.

Seen on a t-shirt, with a picture of the Statue of Liberty, worn by a young woman I passed in the street:

LAY LADY

LIBERTY #1

We are very much

influenced

by the United States

My friend, Bin, was riding his bike on a cold winter night about a year ago. He saw a guy sitting alone, shivering in just a t-shirt. He asked him what his problem was. The guy said he had been tricked out of all his possessions, having given them to someone who promised to get him a job. John Bean gave him 40 kuai ($5). The guy called him back about six months later to tell him that he recently found a job in the construction industry.

New article in The Observer, "Eat less meat and you'll help save the planet." In the last four decades, meat eating in Europe has risen from an annual average of 56kgs (123 lbs) per person to 89kg (196 lbs). People in developing countries ate far less to start with, though China's total per head is now up from 4kgs (8.8 lbs) to 54kg (119 lbs).

The Call to China. That was the call that thousands of Christian missionaries from Europe and the United States heard and which brought them to faraway China. Now this from a review in The New York Review of Books by Anthony Grafton, a professor of Renaissance history at Princeton:

as Lionel Trilling noted long ago, money is -- or used to be -- ashamed of itself. Colleges and universities offered a respected place where malefactors of great wealth could turn their perishable piles of cash into massive lecture halls, libraries, and dormitories, and fashionable space where the malefactor's spawn could gain some polish before they began bilking investors or hiring Pinkertons to break strikes. A century ago, white male patricians awaited the Call to China. Nowadays multiracial groups of boys and girls, many of them Chinese, Japanese, or Korean by descent, sip hot chocolate and sing "Michael, Row the Boat Ashore" while waiting for the Call to Wall Street.

* * *

Pessimism ruled out. "Inveterate worriers" should stop worrying about China's growth, according to the Economist, because this growth is now spreading from the traditionally more prosperous coastal cities to the interior of the country -- places like Kunming. But can the exports which have supported the country's amazing growth, "averaging better than 9% a year over the past 25 years," continue to grow? Indeed, exports are likely to fall, if the Chinese currency is revalued, or if the American economy, where many of them still go, starts to slow down. Not to worry, though, because several factors will mitigate: "For a start, its economy, though trade-dependent, is not excessively so. Its ratio of exports to GDP stands at around 30%: high by the standards of America and Japan, but nothing out of the ordinary compared with European or other East Asian nations."

And domestic consumption is now kicking in as a spur to growth. Prosperity is spreading and more Chinese can now afford "life's little luxuries." The country's domestic economy is thus becoming 'a powerful engine of growth in its own right, just as happened earlier in Japan and, indeed, in America before that." Not that there aren't hurdles still to be jumped, the main one being state-control of sectors of the economy and protection of "inefficient state-owned firms that ought to go bust".

The key fact is that China for the foreseeable future will remain the world's lowest-cost manufacturer of most household items. "So the process of allowing its hundreds of millions 'deprived of material comforts by the insanities of Maoism' to catch up must in the end guarantee a healthy home market. Caution about China is in order: it has gigantic political and social problems, not to mention severe energy shortages and a terrifying level of bad debt. Pessimism, though, is not."

* * *

The preservation of Oriental biodiversity -- an immense but fascinating task even when confined to China, even when confined to Yunnan province. Just making a beginning is difficult. Take plants, for instance. China has over 30,000 species, perhaps a third more than the United States or Europe. If you want to keep track of these, you need their names. In fact, at the present time, the names are changing, many of them. A decade long (or more) international effort is now underway to update and revise the taxonomy of all Chinese plants, the Flora of China project. (This reminds me that we once had a guest in DC, a woman from NYC, who stared at the Flora of West Virginia volumes on our bookshelves and said, "Who is this Flora? And why are there so many volumes about her?").

Once the names settle down, a preliminary prioritization is needed. Which are abundant or common and in no danger of extinction, and which might be threatened? Even if these questions are asked only of Yunnan province, the task is substantial because Yunnan has perhaps two-thirds of all of the plant species in China, an incredible amount for a single province.

(One might think that botanists, plant professionals, are answering these questions, but in fact botanists are mainly concerned with a different task of enormous complexity: describing the characteristics of each species and preparing a series of steps, which they call "keys," one needs to go through with individual plants in order to identify what species it is, however similar it may seem to another species. And then there is periodic revision of all this as new knowledge comes to light, such as is going on now with the Flora of China project.)

Preliminary prioritization requires follow up in the form of determining and recording where species thought to be under threat of some kind are located and how many of them there are in each place. The threat need not be in the form of something like deforestation or road construction: extreme rarity is a form of precariousness that threatens existence in a meaningful sense.

Artemisia annua, sweet wormwood, a spiky-leafed weed with yellow flowers, is abundant in a large area of the world, and in no danger of extinction. But

the immense benefit drawn from it serves as a useful backdrop against which to view the loss of other possible benefits when any species goes extinct. And the compelling story here involves China, including Yunnan province, at the very center. Mao, in the mid-1960s, ordered Chinese science to discover malaria-fighting drugs as a means of helping his ally, Ho Chi Minh, win the Vietnam War. (Quinine was becoming increasingly ineffective). Two teams, eventually consisting of more than 500 scientists, set to work in the midst of the Cultural Revolution, each pursuing a different approach. One screened 40,000 known chemicals for antimalarial effects. The other, headed by Tu Youyou, proved to be more effective and pursued leads on offer from Traditional Chinese Medicine, TCM. Researchers were sent into rural villages to ask local medicine men and women for their secret fever cures, especially those derived from plants. Qinghao, a name carved into tombs as far back as 168 BC and usually administered as a tea, showed particular promise. Qinghao is Artemisia annua.

But the chemical structure of qinghao was very largely unknown, and its mechanism of action was a mystery, as were many other things: what a maximally effective dosage would be; what dosage would be safe; how best to extract it; how best to administer it -- pill, injection, suppository? Moreover, nine other substances from the TCM search also needed exploration. By the time it was discovered what the crucial chemical in qinghao was, now known as artemisinin, the war was nearing an end. Nevertheless, clinical trials proceeded, trials which demonstrated the drug's great power in parasite-killing but also that the body cleaned the drug out so rapidly that leftover parasites were able to rebound quickly. A process of combining artemisinin with other drugs was then commenced, a process which ultimately proved effective. Ironically, one of the combinatory drugs was mefloquine, a drug the US had developed for its soldiers, but which produced nightmares and paranoia in some who took it.

Today, artemisinin is the primary drug used in the treatment of malaria. More than 400 million doses of the drug are administered each year. No career I know of offers more opportunity to benefit humankind than drug discovery. Obviously, the discoverers and those whose diseases are cured both want all the opportunities biodiversity has to offer. Losing a species is losing opportunity.

* * *

The story of Zhou Jintao (Peter) continues. Peter is the man I described last year who had known the Flying Tigers when he was a young man and who had spent more than two decades in prison here as a political undesirable.

Last spring, Bin and I went over to the old people's home to take him to lunch, only to find that he had just been taken to the hospital that morning. We called again several times in the interim, only to be told each time that he was still in the hospital.

We were worried about him and eventually decided to go over to the hospital and see him there. The hospital is over near the Bird & Flower Market. Given the speed with which buildings decay here, I would say that the hospital is about 15 years old. Three beds to a room. We got there about a quarter past noon, always a bad time because everyone is out to lunch. We decided to just go upstairs and ask at each nursing station, since the reception desk was unmanned, or rather unwomanned. We did this for four or five floors, but without luck. The hospital was not run down, but it definitely shows signs of wear. At one station there was one of those machines that monitors pulse rates -- the kind that "flatline" when the patient's heart stops -- but we couldn't tell who it was hooked up to, if anyone. A few people were wandering around; the nurses (perhaps they were doctors) looked harried. A patient, an old man in a jacket, came out of his room into the hall, looked around for a place to spit, and then spit on the floor.

We went out and had dumplings for lunch and came back at 2. The woman at the reception desk said she had no way to search her computer by patient name, but we finally determined that she could search by intake date and that an approximate date would be good enough. Here we had success. We were surprised to find that he was in ward 7, floor 9, bed 15, of the new building, a building where, apparently, party officials have first call.

I had been by this building several times but had had no idea it was a hospital. The first-floor façade and entrance way are built in traditional Chinese style, featuring a carved wooden lattice. This is very unusual for any sort of new building in Kunming at this point, let alone a hospital. Once inside, however, everything is marble and granite and could be anywhere in the world.

At the nurse's station, the sign said, in English, "Cadre station No. 1." We found Peter in his room. He was dressed and in an easy chair next to his bed, watching CCTV-9, the station in English. He had one of those things that supplies oxygen to the nose around his head. He had the remote control in his hand. He had fallen asleep.

I woke him, and he was delighted to see us. He knew my name, and we quickly determined that, far from being at death's door, he was in good shape. He said that he had had a pain in his back and in addition had been unable to sleep for four days straight, so he had decided to go to the hospital. His room was very nice, better than his room at the old people's home (he has a sister whose home he spends his weekends in). I think he was treating this as a kind of vacation.

How did he rate a cadre's room?

He rated it as a veteran.

Which war? WW2? Korea? No, he had been a member of the guerrilla forces who had thrown Chiang Kai-shek out of Yunnan from February to December of 1949. Here is a man, a banker, who was imprisoned as a "political undesirable" for 21 years, starting in 1958, and it turns out he had fought for Mao!

Actually, he didn't do any fighting. He was an instructor. Many, perhaps most, of the troops could neither read nor write. If you are going to run an army, better teach the men to read and write, so they can, among things, understand orders. That must be the theory.

We looked Peter up again recently but couldn't connect with him -- back in the hospital. I hope it's just another vacation.

* * * * *

Quite a few things new at the lake this spring.

Thinking about these changes, though, prompts me to recall something I've altogether forgotten to mention. When we first arrived at Green Lake, in September of 2002, you had to pay a fee if you wanted to go through one of the gates and walk around on the central "island." The fee was small (something like a quarter, as I recall), but it had the effect of confining many people to the walkway around the lake and venturing inside only on special occasions. The fee was abolished sometime after we arrived. I've forgotten why, but I think it was in celebration of an anniversary of Mao's victory over Chiang Kai-shek.

The part behind the gate nearest to our apartment reopened several months ago, with new paving tiles throughout. Similar renovation was made on the other side of the park, even though that had been previously renovated. There are also now little white fences around the base of each tree along the walkways -- the pickets crisscross diagonally and seem, oddly, to be made of cement. More significantly, the whole park has been made kid-friendly. There are now little benches facing the water that consist of two rabbits or turtles or squirrels or penguins carved from stone, on their haunches, holding with their paws a rectangular piece of polished gray stone for you to sit on. The ride which our daughter liked, the one where you pedal a surfaced submarine around a small lagoon and shoot a laser at military-looking mines -- which spout water when you hit the target -- has had its scruffy old mines replaced by new dolphins and other appealing animal figurines. Even the submarines have been replaced with canopied open pedal boats. Several free-standing planters have been added in various venues, designed to look somewhat like cartoon characters.

The bumper car ride I mentioned last time finally has a shiny new side-building made of yellow enameled metal. I saw the bumper cars in action for the first time the other night: seemed rather like the highways. Certainly, the drivers, who included a lot of adults, enjoyed banging into each other. A miniature amusement park for very young kids has been installed in an area behind the pagoda in which our daughter celebrated her 8th birthday with her friends. An unused building just inside the north gate was converted in a matter of weeks into a two-story restaurant with an outdoor terrace on the upper floor (serves noodles, nothing special). And behind a Chinese wall, in an area that was not much used even for the potted-plant nursery it had been originally, has been constructed a beautiful new tennis court. I need to figure out how to get permission to play there.

* * *

Other things also continue to change, really too fast to keep track of them all. In the very first days when our family (and our pooch) came here almost three years ago, daughter Alex and I went for a short stroll to see the neighborhood around the university guesthouse where we were staying. We walked up the block, around to the left past a vest-pocket park and a public toilet, and eventually into a narrow lane where we heard the sounds of kids in school behind a tall brick wall on our right. Above the wall, and back a bit, we could see the open windows in the four story structure the sounds were coming from. I said to my daughter, "Maybe that's the school you will be going to." She was silent, daunted by the prospect of attending second grade in a language she did not understand.

"Ok, I'll go -- but I won't understand a word they say," she said emphatically as we escorted her to the school's gate about a week later -- it was in fact the school she and I had heard and seen on that first day. Since then, I have walked through that crooked narrow lane, too small for cars (but not for bicycles and motorcycles), a thousand times. It is my favorite route for walking from my apartment near the lake to my office.

The other morning when I headed into the lane, I sensed something different. The wall that runs along it actually encloses an apartment complex, and only at one point comes into contact with a corner of Alex's school. Incredibly, on the lane side of the wall, in the slim space between the lane and the wall, several small apartments (if you could call them that) had in the distant past been built, one of them a couple of narrow rooms occupied by an ancient couple who kept roosters in cages. I used to exchange greetings with the woman every morning (I waived, she smiled, her glass eye sparkling). The couple had disappeared when I got back to Kunming last fall, and the apartments were vacant. This morning, these structures -- and the wall there too -- had been knocked down. Everything was rubble, dominated by one of those caterpillar machines with a giant arm that scoops up enormous amounts of bricks and tiles and earth.

Four four-year old boys, adorable, dirty street urchins, stood there absolutely transfixed by that machine. They settled down on a ledge on the other side of the lane. The boys ignored the calls of their mothers from down near the little toilet building. Instead, they watched in awe as the machine did its tricks. (The wall was rebuilt by the end of the week).

* * *

The route from apartment to office also takes me on a footbridge over the heavily trafficked (usually traffic-jammed) 1-2-1 Road. That bridge was the first image I ever saw of Kunming. Three years ago, while using the internet to research where we might go for our year in China, I picked up on the fact that Kunming had a lot to recommend it ("The City of Eternal Spring"). And I found a website put up by a professor of journalism at a small school in South Dakota who was then a visiting teacher at Yunnan Normal University. His family had been given an apartment in a building that overlooks one end of the bridge, and he had put onto the internet pictures of the view from his window, among other images. Since I have been here, I have walked over that bridge every day.

The bridge has always been crowded with nanocapitalists selling everything from goldfish to pencils and stickers to CD's to posters to fried potato slices on a stick, slathered with red pepper sauce. This always made it difficult to get by, especially at noon and in the evening when school children on either side of the bridge are pouring over it in both directions and workers headed home are walking their bicycles through the crowd. The half block which leads up to the bridge has always been a sort of an extension of the bridge itself, though dominated by fast food vendors doing a brisk business with the students from the university, who come out the small west gate to get the cheapest food in a city of cheap food -- omelets, fried potatoes, a sort of Chinese burrito, etc.

Periodically, the police would come by and clear out the vendors, none of whom had a permit. The vendors always had an eye out for when the police were coming and would wheel their carts to safety, embers glowing, as fast as they could. But now the police are serious. They have set up a booth on one end of the bridge and are permanently stationed there. This has changed the whole area. What was once noisy and bustling is now just another place to walk.

That contest between the vendors and the police characterizes for me what one sees and feels about the way life is actually lived in China today. An industrious and still relatively poor people dealing with the rules and regulations which a higher power has laid down about them and their future development. Each individual vendor in flight may have tiny dimensions within a larger picture. It is not war, nor even a national campaign to get people to do something like combat AIDS or drive cars. But the tiny dimensions seem somehow multiplied a billion-fold -- here is where the feeling comes in -- and one believes that taken altogether these events sink into the center of China with even more weight and do more to reveal the spirit of the times than any statistic or pronouncement from the Tartar City.

* * *

A visit from the military. Not the Chinese military, but the US military, and right here in Kunming! Probably through my neighbor in DC, a Colonel Hogan contacted me by email, asking for information about who his class in environmental pollution could speak to when they came to Kunming for a couple of days. I tried to fix them up with a professor who is a specialist in "restoration ecology," but it turned out that he is not so much an expert in restoring polluted lakes as in how plants distribute pollutants and other chemicals within their cells. My colleague here was then kind enough to step in. When they finally arrived, he gave them a slideshow on the province and arranged for the Deputy Director of the Kunming Water Research Institute (part of the provincial government) to speak to them and to take them out on Dianchi (Lake Dian), the very large, heavily polluted lake that adjoins Kunming. The students were officers, mainly, and a few civilians who work for the military. They are taking courses at National Defense University (www.ndu.edu) - specifically, NDU's Industrial College of the Armed Forces. (The idea is that since industrial supply is such an important factor in war, the armed forces should study industry). ICAF is headquartered at Fort McNair, near the Navy Yard, in Southwest DC. Fort McNair is a historic place: it is where the "Lincoln conspirators" were hung.

Hogan turned out to be an Australian. He told me there is a chair reserved for an Australian and one for a Canadian on the faculty of ICAF. I told him this seemed like small compensation for all the military trouble we have gotten Australia in over the years - a role that Winston Churchill used to play. One of the other teachers who came with Hogan and about twenty students was a former CIA guy who speaks Russian and what seemed like a dozen other languages, including Dutch, Romanian, and Bulgarian. Another was a Stanford Law grad who came with the Clinton administration to the State Department, where she was (I think) a Deputy Undersecretary for Oceans and the Environment. The four of us had a nice dinner at one of the few old structures that instead of being torn down has been renovated and turned into a restaurant. They were stunned when the tab for all four of us, which included our beer, came to only 84 kuai, about $10. I walked them back to their hotel on the lake, in front of which an "English Corner" was taking place - about a hundred students, and others, who want to practice their English congregate weekly at the same place and talk to each other; foreign guests are most welcome.

* * *

A visit from HK. When I was in HK on my way back to the US in December, one of my professor friends there told me that his university had an "Industrial Attachment Scheme" which paid for students who are between their second and third years to spend a summer working at a business; several of his students had requested work at an NGO in China instead, and he wondered whether I would be willing to be the NGO host. I told him I was going to be back in the states for the summer, so I wouldn't really be able to train them and supervise them on a day-by-day basis, except possibly via email. It turned out that their exams would be over very early and that they would be ready to travel by May 16; that would give me at least three weeks with them, the first of which would be a week of training in our methodology. My co-worker, who has a Master's degree, could be the onsite supervisor for the rest of the time. We decided to give this a try, and when I returned to HK at the end of March, Paul had three students for me to interview, with the thought that I would choose two of them. I liked all three and dreaded having to leave one out, but Paul then somehow arranged for all three to come. Two of them have been here a week and have already been turned into first-class conservation scientists, one now working on acquiring range and habitat data for all of the fish and reptiles of China and the other on putting information about the province's parks and preserves into the database. They will also have the primary responsibility for training their newly-arrived colleague, although Bin and I will also play a role in that. All three speak excellent Mandarin as well as Cantonese and English. They are shy about their abilities with Mandarin, but I have heard them speaking with grad students here, and I am impressed with how smoothly it all goes.

The things that do give them some trouble, however, are the simplified Chinese characters. Starting around 1920, many Chinese intellectuals began to propound the view that traditional characters were cumbersome, difficult to learn, old-fashioned. Some even wanted a wholly alphabetic system. Simplification of the characters then suggested itself, though nothing came of the suggestion until the civil war had been settled. More than fifty years ago lists of simplified characters were officially adopted and the alphabetic system called Pinyin was introduced. Hong Kong, and Taiwan of course, ignored all this. One advantage this gives my HK students is the ability to read the older labels on dried plant specimens preserved in herbaria here - labels often prepared seventy-five or a hundred years ago. (With the end of the UK lease in 1997, it should be noted, and the handover to the PRC, Hong Kong has increasingly supplemented its native Cantonese education with courses in Mandarin that employ the simplified characters).

* * *

My colleague was recently made the first UNESCO Cousteau Ecotechnie Professor in China. The head of the Asia section of UNESCO, who is Japanese, and his assistant in Beijing for environmental affairs, who is also Japanese, came down for the brief ceremony. Afterwards a few of us toured the campus with them, one of the highlights of which is one of the few Chinese-looking buildings on campus. This building was the place where, under the ancient system, candidates could present themselves to take the imperial examination. This examination, remarkably, was open to all males regardless of social standing (though in practical fact only the wealthy could afford the many years of study and the distinguished tutors necessary to be in a position to take the examination). Successful candidates could, after many more examinations in other locations, become mandarins and eventually rise in the civil administration of the largest country on earth. This particular building is also of interest because it was the place where a famous local poet gave a speech in the late forties in which agents of the Kuomintang government claimed to hear undertones of sympathy for Mao and his peasant revolution. After the speech, he was assassinated.

The building is still used today for meetings and various other activities. The head man from UNESCO walked over to some bulletin boards outside the main doors. He came back and said he could read about 60% of the characters. He then lamented at some length, and amusingly, the passing of the days when Chinese and Japanese could "talk" to each other by writing out characters for the other to read. "This was a very good system - and then they had to go and change it!"

* * *

One of the couple of western restaurants that we laowai frequent is named Salvador's. It opened first in one of Yunnan's most scenic tourist destinations, the old town of Dali, surrounded by snow-covered mountains and a large lake - it was Salvador's of Dali before it moved here to Kunming. I discovered that Salvador's makes and sells fresh pesto. I bought some to take home the other night and put it on cold pasta noodles, with olive oil and parmesan cheese. I was scarfing this down before going to my Monday night badminton session, when I decided to turn on the television to see what was on CCTV-9, the English-language channel. A dull show called "Dialogue" was on. Many foreign guests, often paired with some Chinese professor who studies the West, appear on this show, where they are asked questions like "What factors will affect the growth of China's automobile industry?" or "Does America still believe in the One-China policy?"

But this evening the guest was an attractive young woman from the Ministry of Commerce, and she was discussing the sanctions America was threatening to impose on China's textile industry. She would do well at an American law school and pressed China's case with uncommon vigor. Essentially her argument was that China for years suffered under US and EU quota systems, then it reconstructed (at considerable cost) its economy to be able to join WTO, and now that its production efficiencies are winning customers, the West is talking about sanctions. She also noted that much of the growth in China's exports is actually coming from local firms owned in large measure by Americans and Europeans. Throughout her dialogue a subtitle appeared that said "Textile dispute." I therefore couldn't tell who she was until near the end, when "Ministry of Commerce" appeared, along with her name: Yuan Yuan. This is almost too good to be true, for the currency of China is, of course, the yuan. They tell me that there are a number of characters that can be used for what in pinyin is rendered as "yuan," but I'm afraid I just can't resist thinking of this woman as Money Money.

* * *

t has hardly rained at all since last fall, and now as summer approaches the rainy season is at least three weeks late. There is, moreover, not a drop of water in the offing.

A recent Economist had an article entitled "China's Water Crisis," based mainly on recent speeches by a former Stanford professor, John McAlister, who has founded a company, AquaBioTronic, which possesses a technology for converting waste water into drinkable water. He is having trouble selling his technology in China, despite the crisis. He maintains, if I may put a few words in his mouth, that that great sucking sound that George Bush heard when NAFTA was signed is here in China a real sucking sound - water being taken from the water tables. Almost every body of water in the country ("never especially blessed with water") is polluted. As a consequence - China's miraculous growth is in jeopardy. (McAlister uses the term "ecological suicide"). His view is that this will not only affect China, but the world economy as well since so much of world economic growth these days depends on the growth of the Chinese economy. Wen Jiabao, now China's Premier, publicized the water crisis some years ago when he was a mere Deputy Vice-Premier, and it has been put into five-year plans ever since and given the highest priority, but none of this seems to be having much effect.

This crisis is going to be felt the hardest in the more industrialized parts of the country, which do not include Yunnan Province, whose income comes 70% from tobacco. Even a genuine drought here would likely have effects for only a year or two (I would imagine), whereas in other parts of the country, the crisis looks like a permanent thing. On the other hand, I suppose that China's missing sense of urgency has something to do with its 3,500 years. The traditional view is that the history of China is the history of a settled civilization contending with nomadic peoples who reside in Asia's interior. This has of course produced many crises of the most severe kind over the centuries. There have of course also been frequent natural disasters like the flooding of the rivers and earthquakes right in the center of some of the most densely populated areas in the world, to say nothing of the war with Japan, or the civil war, or the Cultural Revolution. Yet that settled civilization seems always to prevail, teaching the nomadic conquerors how to take a bath and read a book, somehow restoring what nature or war has devastated, and gritting its teeth and smiling about what the Twentieth Century handed them. Is the present crisis all that different? That may be the view. On the other hand, that sucking sound could be a warning that perhaps there are things that can't be reversed.

Meanwhile, the nights here now are balmy and dry and beautiful, and one wants to stay out past midnight in the open air, talking of Robert Louis Stevenson and violence in Buddhism, sipping China's only decent wine while one's friends drink the local beer. Every day, warmer than the last, the young women wear fewer and fewer clothes. Where will it all end?

* * *

From the Selected Works of Mao Zedong (December 15, 1945):

No matter how the situation develops, our Party must always calculate on a long-term basis, if our position is to be invincible. At present, our Party on the one hand persists in its stand for self-government and self-defence in the Liberated Areas, firmly opposes attacks by the Kuomintang and consolidates the gains won by the people of these areas. On the other hand, we support the democratic movement now developing in the Kuomintang areas (as marked by the student strike in Kunming [4]) in order to isolate the reactionaries, win numerous allies for ourselves and expand the national democratic united front under our Party's influence.

The editors' note 4 says:

On the evening of November 25, 1945, more than six thousand college and middle school students in Kunming, capital of Yunnan Province, assembled at the Southwest Associated University to discuss current affairs and protest against the civil war. The Kuomintang reactionaries sent troops who surrounded the assembly, fired on the students with light artillery, machine-guns and rifles and placed guards around the university to prevent teachers and students from going home. Subsequently, students from Kunming's schools and colleges joined in a strike. On December 1 the Kuomintang reactionaries dispatched a large number of soldiers and secret agents to the Southwest Associated University and the Teachers College where they threw hand-grenades, killing four people and wounding over ten. This incident was known as the "December 1st Massacre".

For the website where Mao's Selected Works appear Click here.

The graves of the four martyrs are in a corner of what is now Yunnan Normal University. I attended the ceremony there commemorating the 60th anniversary of the December 1 event. Yunnan Normal, the "Teachers College" to which the note refers, is one of three university campuses along the busy "1-2-1 Road" which I cross each day, using the pedestrian flyover. Until a few days ago I had not realized that this street is named for this event: in effect, "12-1 Road" or "December 1 Road."

Southwest Associated University was a consortium of faculties fleeing further and further south from the war zone in northeastern and then in central China: National Peking (now Beijing) University, Tsinghua University (aka Qinghua University, often called the MIT of China), and Nankai University. The site now occupied by Normal was the main site where these faculties did their teaching, starting in the late thirties, for about a decade or more.

My friend John Israel, recently retired from his professorship at University of Virginia, and the first American scholar to make his way all the way to Kunming after the US recognized the PRC, has written a history of Southwest Associated University, Lianda: A Chinese University in War and Revolution (Stanford 1999). I have known about this book since I first met him in 2003. I had a general intention to obtain it and read it but had not yet followed through.

Then a month ago, I was reading a copy of The London Review of Books which a friend had given me and which I had brought with me to China. The review (by Frank Kermode) is of a new biography of William Empson, often called "the greatest English literary critic of the 20th century."

Kermode:

In August 1937 [Empson] set out on another Oriental adventure when he accepted a three-year appointment at the National Peking University. At much the same time the Japanese invaded China, and when he arrived, via the Trans-Siberian Railway, he had no job to go to. . . . The Japanese particularly hated the northern Chinese universities, which were forced to flee. Empson went with them [writing about] the food, the conditions ['the savage life and the fleas and the bombs'], the complex political situation, in which the Kuomintang was in conflict with the Communist Party as well as with the invaders. Most impressive is his admiration and respect for his colleagues; the company of these professional scholars allowed him to feel that, despite the uniquely difficult conditions, what he now belonged to was a real university.

Empson:

Camp life was fun; I was in very good company . . . I hoped I wasn't making too much noise typing about the use of sense in Measure for Measure [later a chapter in his magnum opus, The Structure of Complex Words, published in 1951] . . . I know the quality of the men I have to eat with. I suppose there is no other country in the world where that type of man would take the migration and its startling hardships, not merely without false heroics, but as a trip that leaves you both waiting to collect news about your special branch of learning and also interested in the local scenery and food.

The faculties fled first to Changsha, in Hunan Province (the province our daughter was born in), and then, when that was bombed, to Kunming. John told me that actually the humanities faculty was for the first year in Mengzi, which is about half way to the Vietnam border from here, but that when proper facilities had been constructed in Kunming, it joined the other faculties here in the capital city. I was somewhat startled to realize that Empson, a famous but rather esoteric Englishman, trod the ground I tread daily. (But then, on the other hand, I had never in my life seen a picture of Alain Robbe-Grillet, the French anti-novelist, until I saw one the other day in the window of a tiny used book store here in Kunming which I pass regularly. Could he, too, have been here at one point?)

I first learned of Empson when I was studying philosophy of language as an undergraduate. Empson was from the literary world, and so had but provisional standing with the philosophers; still, the philosophers were at the time interested in "ordinary language philosophy," an approach which held that many of the hoarier questions of philosophy would go away if you realized they involved linguistic distortions and were far from the language that people ordinarily use. Empson was a very, very close student of the way language has been used. He could find hidden meanings in almost anything, and often one contradicted another. His most famous book is Seven Types of Ambiguity. All this made him of interest even to philosophers, not that I ever managed to plow my way through the whole book.

But back to the ceremony commemorating the 60th anniversary of the December 1 event. The ceremony was brief: a speech by the son of one of the martyrs; a speech by a Beijing woman from the Central Committee (retired - ever the backwater, Kunming). Everyone stood during the ceremony. There were about 200 gray-haired people standing in front and, standing in formation at the back, a further 400 students and police officers (I'm not sure why the police were there). Afterwards, the officials left and the rest of us milled around among the graves and associated memorials. I met the son and grandson of Wen Yiduo, the famous poet famously associated with Yunnan, who was assassinated by the Kuomintang about seven months after the December 1st Massacre when he turned from scholarly to more political modes. He had lived along the walkway behind the apartment complex in which I now stay. There is a small memorial to him there with a rather nice portrait painted onto a wall; it stands just outside the gate to a primary school that was built on the site of his home. Wen Yiduo looked somewhat like Trotsky, at least in this portrait, which is taken from a famous photograph.

I learned that 150,000 people "then half of the city's entire population" turned out for the funeral parade for the four martyrs (only one of whom was a Communist). They were not allowed to carry banners. Instead, they sang a song, which four of the older people at the memorial ceremony sang again for the media - several times.

We toured the brand-new extension to the museum next to this site. The young women docents were stunned that John knew so much about all this and could fill them in on many facts. He identified many of the people in the photographs for them, including the one Westerner pictured (in a faculty photo), Robert Winter, an American who apparently took over Empson's subjects when he left. Robert Payne, author of many books on communist societies, also taught at Lianda. Payne was a good friend of Wen Yiduo, and Payne kept and published extensive diaries about his days in Yunnan. The extension ends with a room depicting many of the great scientists who attended Lianda, the most prominent being the Nobel laureates, C.N. Yang and T.D. Lee. Yang was the son of a Tsinghua mathematician. After graduating from Lianda he studied with Fermi at Chicago, where he got his doctorate, and then went straight to the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. He did much of his work at Stonybrook. As of 2005, he is still alive and resides in HK. T.D. Lee followed a similar path.

The net result of this, for me, was that I bought and read, and thoroughly enjoyed, John's book. It provides a perspective on the years from Japan's declaration of war to the victory by Mao in the civil war which is very different from the more standard accounts. One gets to know very human individuals, not just high military and political figures. One of the things I found most interesting was the contrast between the Lianda faculties and those of the university they found already established here in Kunming, Yunnan University. Lianda professors came from eastern China and consisted largely of men who had obtained a PhD from an Ivy League school in the US. Yunnan University professors, in contrast, had higher degrees from the Sorbonne or the University of Paris, and their second language was French, not English.

* * *

Where will it all end? That was the question with which I ended the last episode in these Green Lake reflections. The morning and the afternoon of the next day, Sunday, May 29, were as sunny and as hot as usual. I learned at brunch - a group of us about to leave Kunming for the summer had gathered for brunch at the best hotel in town, the Harbour Plaza - that three of my friends had bicycled about 20 km. out of city the previous day, north to the largest of the reservoirs that supply Kunming. The reservoir was mighty low, though not absolutely dry like some of the other reservoirs.

There were never any water use restrictions during this whole period, and large trucks continued to go around spraying water on trees and lawns in the universities and in parks; the gardeners in my own little apartment complex continued to water everything daily.

I learned, however, that the provincial government had not been idle: they had placed around 400 artillery pieces around the city with hopes of using them to seed the clouds. One problem with this: you need clouds to seed if you are going to seed clouds, and there were none.

I also learned that the government claimed to have set up a massive pumping operation, not for pumping water out of the water table, but for moving water around from one reservoir to another. One problem with this: when all of the reservoirs run out of water, there is of course nothing to pump.

We walked back through Green Lake park after brunch, a hot trip, cooled somewhat, it must be admitted, by the shade of the trees. We noticed that the water in the shallower parts of the lake had turned bright green. The purest algal bloom I have ever seen. This had the effect of enhancing the beauty of the already beautiful lotus flowers which had recently appeared. Pierre mentioned that as a teenager he had one summer been given the job of minding a neighbor's swimming pool. Things went along fine for a while, but then one night, the water turned green. He never was able to correct this, and the owners had a devil of a time with it also when they returned.

About 4:15 pm it clouded over and began to rain. It rained steadily for about two hours, then cleared up. The next morning was drizzly; it felt like the rainy season had returned at last. But it hadn't. Despite a few cloudy days and a fitful drizzle or two, there was no sustained rain for the five remaining days I was in Kunming, and most afternoons were hot and sunny.

On the plane, which left for Incheon at 10 minutes before midnight on 3 June, I read in The Korea Herald that there had been heavy rain and flooding in Hunan province during this same week that the drought in Kunming continued.

Later in June, Pierre emailed me:

Yes, Hardy, the rain began last night. It was rather dramatic to witness, as the sky turned black in the early evening, and stayed that way for a few hours without rain. At around 1am, it began to pour and 12 hours later, is still coming down.

The net effect was to shorten the already short rainy season, normally from late April to around the end of August, by more than a month. Kunming gets very little rain out of the rainy season. It is a city in which dusty shop floors are swabbed each morning and dust continually settles on everything you own. I must say, however, that when I returned at the beginning of October, I saw very little effect of the truncated season. Perhaps the rain that did come was heavier than usual.

* * *

I do know that Dianchi (Lake Dian), the large lake beside Kunming, one of the four most polluted in China, is no healthier. The story of the ecological disaster which afflicts the lake is told in Judith Shapiro's terrific book, Mao's War Against Nature (Cambridge 2001).

The dying of the lake is a consequence first of the Great Leap Forward and then of the break between the Soviet Union and China in July of 1960, when the USSR withdrew its aid and "self-sufficiency" [zili gengsheng] was the response. The leap produced famine, in which tens of millions died. The dying of the people and the withdrawal of aid produced a destructive campaign to turn every scrap of landscape into productive farmland. The campaign elevated one particular community's falsified success in self-sufficiency into a model to be copied everywhere. The campaign resulted here in Kunming in an attempt to convert the marshes protecting and filtering Dianchi into rice paddies. The attempt involved enormous resources, at enormous cost, and was an utter failure. Filling in these marshes was like removing the lake's liver. There is nothing now to filter the pollutants running into the lake from surrounding farmland, and from the city. The lake - China's sixth largest freshwater lake - is now on its deathbed.

There is much more to the story, but perhaps next time. We can also talk about elephants.

* * *

John and I took Peter Zhao out to dinner a month ago. Peter is still doing fine. We took him on a long walk to a restaurant between the Harbour Plaza Hotel and the new skyscraper city library, a restaurant with the odd name of Bamboo Civet. We sat outside on a cool evening, dining on prawns steamed over tea leaves. It turned out that Peter had spent a year at Southwest Associated Universities, until his family ran out of money. On our walk back, we discovered that Peter remembered the school song. So did John. The two of them sang it "forcefully" as we walked along. Many a head turned to see this.

* * *

There is a seven-part documentary on CCTV-9, the English-language channel here, about the life of Edgar Snow, in honor of the centenary of his birth. Edgar Snow is the author of Red Star Over China, the first book about Mao. The book was based on his interviews with Mao in the late thirties. Snow traveled, with the help of cloak and dagger, through Kuomintang lines to the caves of Yenan in Shaanxi Province, where Mao had stopped after the Long March. (The pinyin spelling is Yan'an, but the romanization the Chinese postal system uses is Yenan). The resulting book was a bestseller, and, more importantly, was translated into Chinese and became the main source the Chinese people had about the man locked in a life-and-death struggle with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.

The thing I liked best about the documentary was that in the first show they travel to Snow's birthplace, Kansas City. They find his birth certificate in a small Snow museum. They go to the address listed on the certificate. A Chinese reporter knocks on the door of this typical American two-story apartment building. A young guy answers the door. "We're from CCTV in China, and we'd like to see the place where Edgar Snow's family lived." "Who's Edgar Snow?" He politely shows them around, pointlessly, however, for no particular apartment can be identified with Snow. They then find Charlie Smith, who went to high school with Snow. Remember, this is the centenary of Snow's birth. Charlie Smith is 100 years old and still going strong. He is happy to talk to reporters from China and tell them stories about his old friend, Edgar Snow. I loved Charlie Smith, and I will point him out as a role model to Peter Zhao; may Peter live to be a 100 or more.

* * *

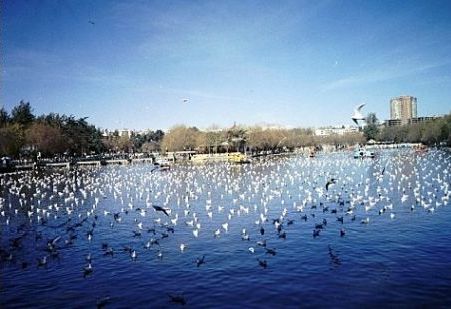

Green Lake? The Black-headed Gulls arrived on schedule some weeks ago, now that it is fall, and the bread people were not a moment behind. I wrote several years ago that there are several thousand gulls, and that "Green Lake is ready for them, with 'seagull bread,' sold by vendors all around the lake. People tear off pieces of bread and toss the pieces up into the air, where the seagulls, whose flocks fly continuously around in a great circle formation, catch them - acrobatically." It is the same this year, and it is particularly lovely because the weather has been so beautiful: cloudless skies and summertime temperatures. The charm of the gulls wears thin in February and March when their droppings have thickly coated the roofs of the pedal boats that people rent, and much else besides.

The lake is still lit up at night. There is a grand way leading in from the South Gate paved with white stone that is particularly beautiful, with the willow trees along either side illuminated in different colors. But even more obscure parts of the park have plenty of lights. And the entire border of the lake, with its carved white stone Chinese railing, is lit on the pedestrian side by lights shining straight up from the pavement and on the water side by lights shining on the railing. My favorite scene is a short white stone bridge with three wide arches. The arches are illuminated from below and are reflected by the lake. I will write later about the groups in the park that perform music on traditional instruments.

* * *

How about if I return to Empson to end this? I read this somewhere, but have forgotten exactly where:

The only religion Empson could ever stomach was Buddhism, about which he wrote a book-length study. To his dismay, The Face of the Buddha was lost when a friend left the only manuscript in a taxi.

I like to think that though it may never be read it was at least in circulation, maybe even still moving around.

Chapters are sometimes supplemented by notes. Click Random Footnotes to see.

Table of Contents

Home page

Welcome to a journey, riding webbook or ebook. We alternate between roughly chronological "feet on soil" chapters and "nose in books" chapters. The introductory web posting

of the first two chapters is in full. Click Additional for other postings. The complete ebook, sans ads of course, is available now for purchase:

Click here